|By James Carney, Senior Gale Ambassador at King’s College London|

Decolonisation refers to the process of attempting to undo the social, political, economic and cultural effects of imperialism on former colonies. Having just completed my undergraduate degree in English and Classical Literature at King’s College London, I have come to appreciate language and the written arts as potent mediums to contemplate, respond to and even resist the weight of colonial history.

My dissertation on Derek Walcott’s 1990 postmodern epic Omeros most thoroughly illustrated to me the nuances and creative potential of colonial victims to negotiate their present and historical standing in response to imperial agents. My exploration of this theme in Walcott’s work was particularly interesting as he ostensibly views colonisation as continuous, from nineteenth-century British and French empires to modern American capitalism, as the same force underlies both processes for the benefit of the typically white aristocracy, eclipsing native identity and homogenising Caribbean culture to artificiality.

Attitudes to decolonisation

The theme of the complex spectres of empire and their relationship to Caribbean cultural identity in Omeros chimes resonantly with contemporary concerns of systemic racism in the West: both the poetic and political attribute racial discrimination and violence, socially and economically, to weighted colonial oppression.

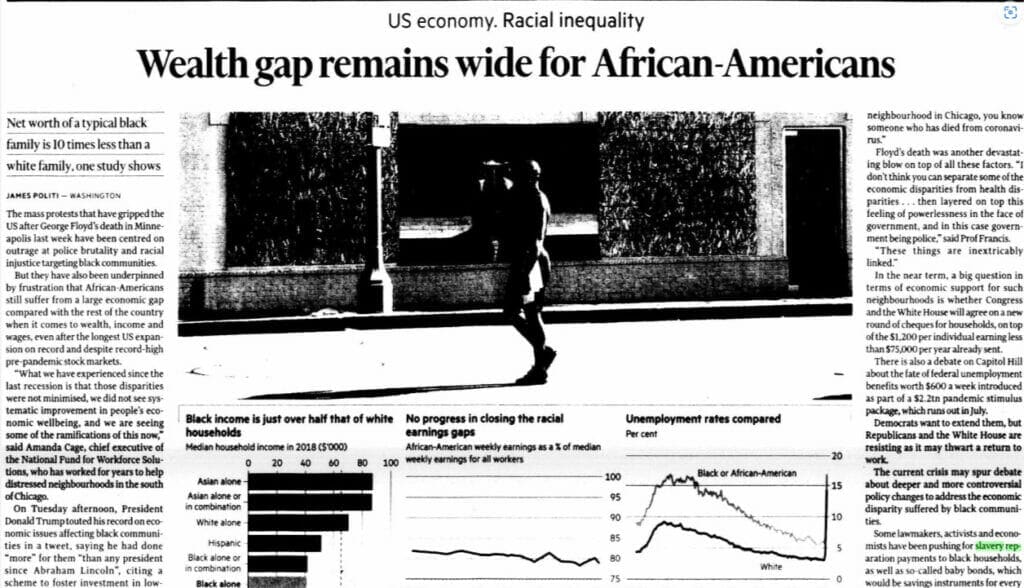

As Walcott warns in Omeros’ presentation of capitalism, the diagnosis of difference by white elites contributes velocity towards greater racial dystopia, especially without imminent systemic deconstruction through decolonisation. Considering the recent discourses of reparations to victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, described by James Politi in the Financial Times Historical Archive as a potentially ‘huge political lift’, discourses of academic decolonisation are surprisingly limited.

A Downward Trend in Explicitly Positive Affection Towards Literary Decolonisation

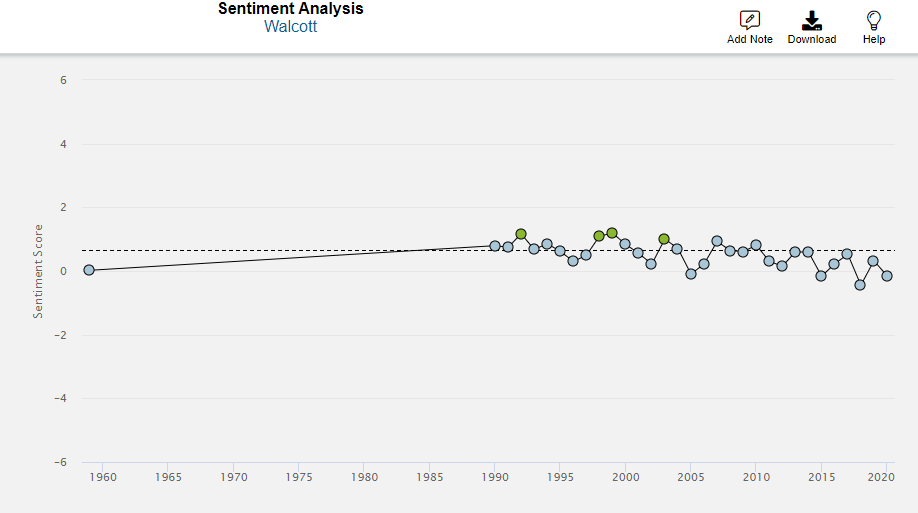

Using Gale Digital Scholar Lab, I created a Content Set of articles related to the terms ‘decolonisation’, ‘Walcott’ (among other postcolonial writers) and ‘poetry’, and limited the date range to articles published between 1990–2023. I then ran this Content Set through the Sentiment Analysis tool in Gale Digital Scholar Lab. The visualisation the tool produced revealed a downward trend in explicitly positive affection towards literary decolonisation in articles from the publication of Omeros in 1990 to the present – a disheartening finding for those who believe in the possibility of a decolonised literary curriculum.

Therefore, in this blog post, I hope to use my own research within Gale Primary Sources to make a minor contribution to a far wider cultural movement looking to encourage greater appreciation of postcolonial literature, so that the academy’s literary canon might one day reflect true global diversity and become a space of equality.

Omeros as Epic

Considering Walcott’s political perspectives, the question of Omeros’ genre has faced much critical debate. Since the Classics (which Walcott consciously references) epic has been the genre of Homeric battles and conquest, Ovidian dynamics of love and power or, most significantly, imperial foundation myths in Virgil’s Aeneid. The influence of such Graeco-Roman poetry on European imperial self-fashioning has been subject to much historical and cultural investigation.

It is apparent in Omeros as well: in Book 2, Walcott alludes to the historic ‘Battle of the Saints’ where the British and French ships take the names of Iliadic heroes as they strive for colonial possession of St. Lucia, to parallel and claim for these colonial activities the epic significance of Homer’s Trojan War. Therefore, Walcott’s occupation of the imperially appropriated genre appears incongruous with his central themes of decolonisation and postcolonialism.

However, after the main character, Achille, hallucinates native Africa in Book 3, he learns that the ‘epical splendour’ of the African diaspora in the Caribbean lies in their survival of the Middle Passage (the stage of the Atlantic Slave Trade where millions of Africans were transported to the Americas). While not necessarily the famed heroes of Trojan battles, Walcott’s diasporic heroes share their fearlessness to endure against the violence of colonialism. They assume Creole variants of epic names like Achille, Philoctete and Hector to suggest that their survival of colonial violence merits the same epic significance as Homeric heroes.

Moreover, there’s also epic significance, as the Creole suggests, in their endurance of cultural hybridity, as Africans, St. Lucians and inheritors of Western culture. In these ways the spectres of ancient epic and its absorption into European imperialism weighs on Walcott’s Caribbean present, not as a constraint on Caribbean cultural identity but rather as an integrated part of this epically hybrid belonging.

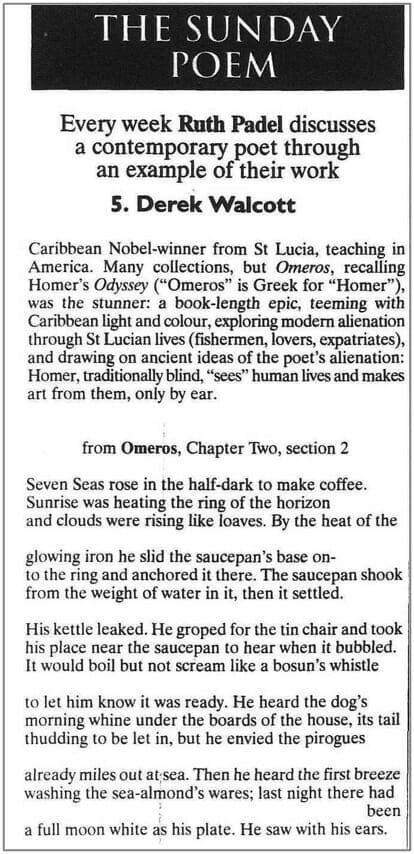

In The Independent Historical Archive, King’s College London’s Ruth Padel discusses a telling scene from Book 2 of Omeros that illuminates Walcott’s epic vision: if, as we have seen, the cultural hybridity of his diasporic characters is epic in and of itself, then a Caribbean epic can simply celebrate quotidian simplicities. Padel’s analysis bolsters such a reading: she observes Walcott ‘metaphorically eliding kitchen and sea’ to illustrate how, in his vision of the Caribbean, the banal domestic is equivalent to the universal epic because a richness of historically charged hybridity occupies both.

Moreover, she identifies the Terza Rima ‘unit of Dante’s Commedia’ which permeates Omeros’ meters to reinforce the theme of hybridity’s epical significance: beyond immediate allegiance to the European epic tradition, the rhythm foregrounds the constant weighing of the past on the present as epic. Dante’s Commedia explores the literary past in the Inferno with Virgil through a Christian lens. By incorporating this rhythm, together with Homeric themes and contemporary St. Lucian concerns, Walcott hybridises his poetics as multiple forces of history and tradition culminate in the epic of Omeros to fit the hybrid cultural identity he sees in the Caribbean. As Padel asserts, these strategies contribute to an epic that claims ‘new momentum and continuity with European tradition.’

Omeros and Haunting

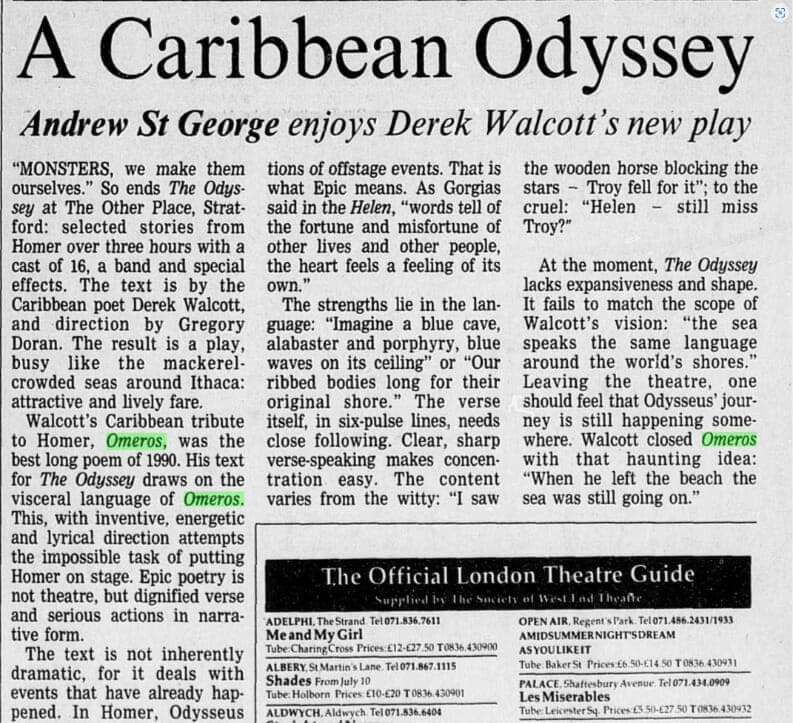

With Walcott’s epic vision resolutely established, the question lingers of what we might take away from Omeros. In the Financial Times Historical Archive, Andrew St George argues that his crucial takeaway was ‘that haunting idea: When he left the beach the sea was still going.’ Here, St George quotes from the poem’s closing line and relates it to the central theme of the sea as symbolic of the tides of culture and of history.

By his reading, therefore, Omeros’ central theme involves temporality and differing ideas of permanence/ impermanence. The same tides of history that shape the present also change it and adapt it: while this history might not be constant, its evolution will be. Such an interpretation provides both a hopeful and melancholic note, as Omeros explores not only pain overcome with colonialism and cultural loss, but equally imminent pain as climate change threatens St. Lucia’s natural beauty and the livelihood of the natives recently restored.

That this idea of temporality and change feels ‘haunting’ to St George intrigues me, as it strikes a profound humanity as the wheel of fortune spins. But it also resonates strongly with Walcott’s epic vision: the endurance of hybrid St. Lucians throughout these endless tides of history, empire and capitalism certainly becomes epic, as their trying appears perpetual and cyclical.

In his epic vision, Walcott integrates the past, yet also succeeds in building upon it so that his poem can haunt the very core of our being. It is this unique quality of the poem that propels contemporaneous relatability, which classical epic arguably lacks, paired with its meditations on race and empire that make studying it such a pleasure.

Postcolonial Writers are Foundational for Decolonised Curricula

As these various sources have demonstrated, Omeros is a complex work built on sensitive engagement with the epic past as well as the Caribbean present. As most university courses on epic include Homer, Virgil, Ovid, Dante and Milton, it is worth interrogating why they so frequently overlook Walcott. His parallels with and allusions to these myriad poets can only enhance readers’ understandings of these works while simultaneously revitalising them for the necessary decolonisation of Eurocentric reading lists. If we want a decolonised curriculum, it is imperative we prescribe the same attention to postcolonial writers as to the established Greats. As we have explored in this piece, there’s a haunting value to Walcott’s work that I hope will make Omeros a classic as widely recognised as the Graeco-Roman and English literary epics.

If you enjoyed reading about decolonisation and Derek Walcott’s Omeros, you might also enjoy:

- Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories

- How Slave Narratives Give Voice to the Enslaved

- Unearthing and Decolonising the Rasta Voice

- Decolonising the Curriculum with Archives Unbound

- Discovering New Points of View about European and Colonised Women Using Gale’s Women’s Studies Archive: Voice and Vision

- How Ancient Egypt Was Presented in Nineteenth-Century Newspapers

- Using Primary Sources to Explore How Courts Punished Interracial Sex in Apartheid South Africa

For a further example of using Gale Primary Sources to study Classical literature, try:

Blog post cover image citation: A photo by Corinne Kutz of The Pitons, mountains in St Lucia in the Caribbean, available on available on Unsplash.com