| By Robert Youngs do Patrocinio, Gale Ambassador at University College London|

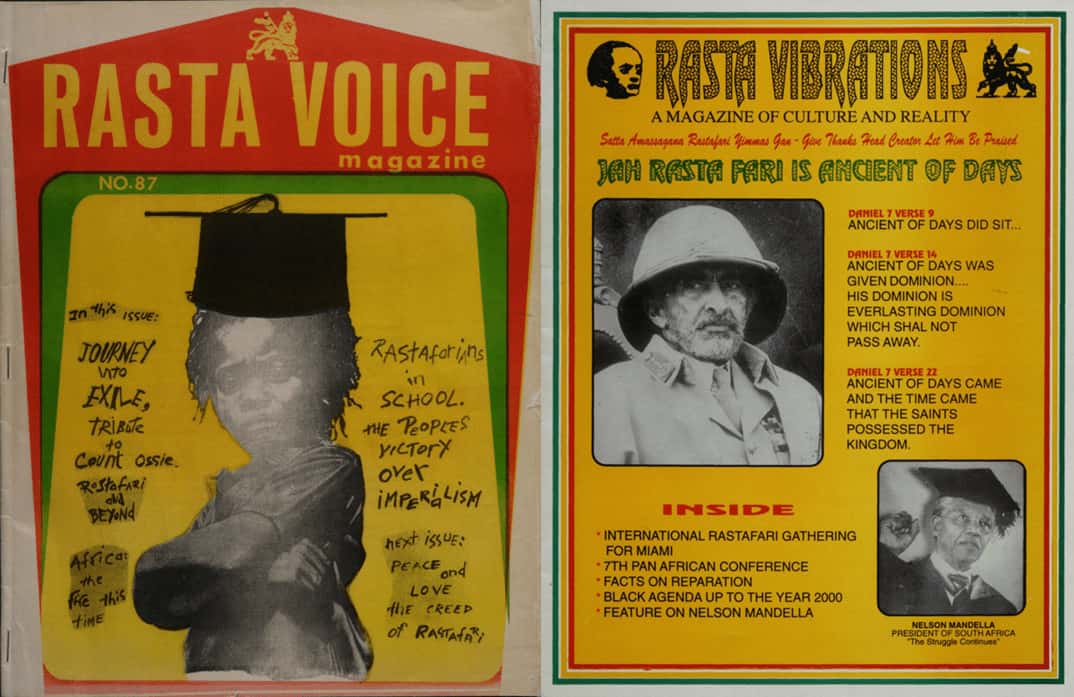

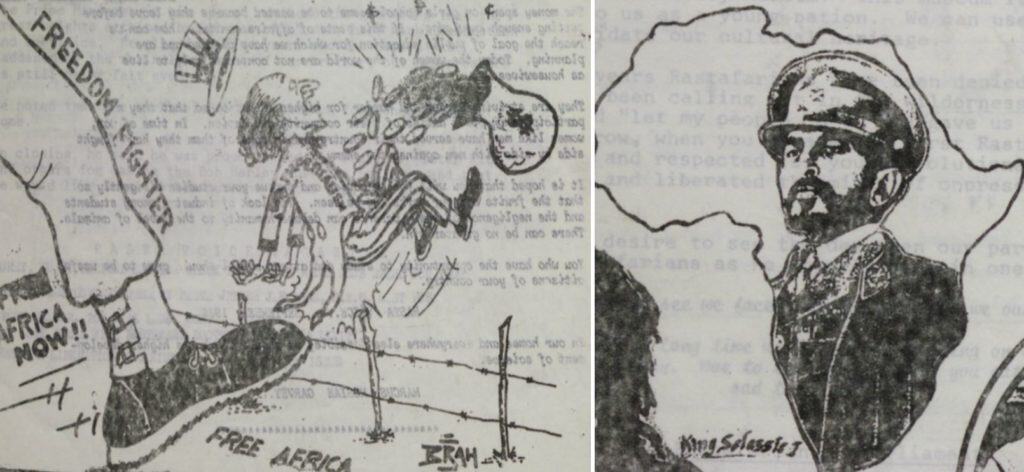

This post will focus on raising awareness of the Rasta struggle to practise their religion, principally using Gale’s Archives Unbound collections, an extensive database of primary sources included in Gale Reference Complete that many university students such as myself can utilise when conducting all types of research. It currently comprises 382 collections (more are added each year), and includes a compelling collection titled: Rastafari Ephemeral Publications from the Written Rastafari Archives Project. The Rastafarianism movement can be traced back to its beginnings in 1930s Jamaica and its strong connections with the coronation of the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie (1930) who remains a principal figure in the Rastafarian religion. As the political cartoon below illustrates, the Rasta faith is rooted in an ideology which believes that Africa is paramount to black individuals obtaining freedom and escaping their physical, spiritual, emotional and historical oppression and struggle against slavery. As a religious belief system, I think that it is important to become mindful of Rastafari traditions and invest time in accessing elements of this culture, due to the significance of its relationship to the black experience and post-slavery trauma.

‘Wrap Collection Volume 1; Rasta Voice; #26 Issue no. 95 May 1986’ (n.d.), Archives Unbound, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/SC5110287229/GDCS.GRC?u=ucl_ttda&sid=bookmark-GDCS.GRC&xid=b0b19bef&pg=21

Rasta Religious Traditions

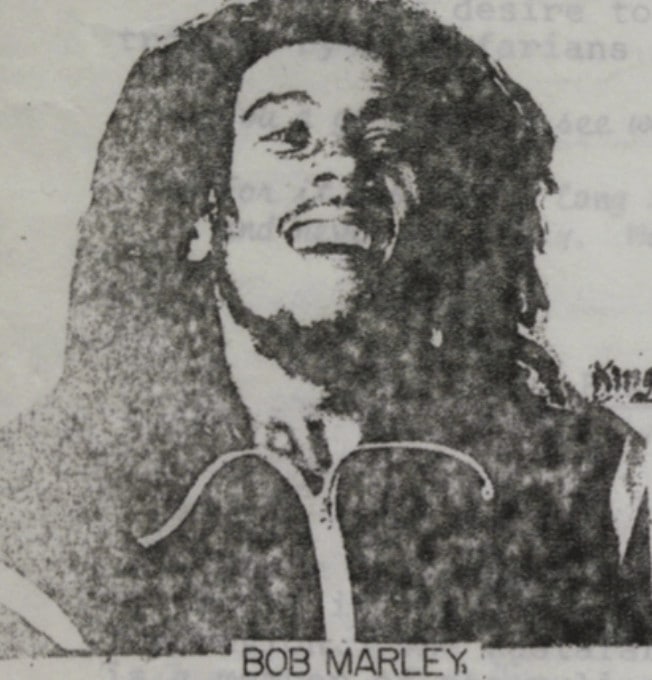

Internationally recognised by the songs of Bob Marley and Dennis Brown, the Rasta community’s message has spread globally and is perceived mainly through reggae music. Important messages about black liberation and oppression are expressed in songs such as Buffalo Soldier, Get Up, Stand Up and Revolution, but to what extent do we really understand this complex movement? Beyond the “locks” and the “ganja,” do we appreciate that central to this rich belief system is the notion of the “holy herb” which is essential to their religious rites and rituals?

Rastas lifestyle choices are religiously motivated and rooted in a central message relating to peace. Ganja, for example, is central to their religion, and is considered to be a “wisdom weed” allowing individuals to reach an important meditative state of higher connection to their spirituality and faith. But, when researching this using Gale’s resources, I found an article from the 1970s – a time when Jamaica was home to only 7000 Rastas – entitled “God is Black and is Living in Ethiopia” which describes how “most avenues of work are closed to [Rastas] because they wear dreadlocks and smoke marijuana.” This highlights the historical discrimination the Rasta community faced, which has since intensified in Jamaica and around the world, even though their numbers have now grown to over one million. Discriminatory attitudes towards Rastafarianism have resulted in in their religious culture becoming synonymous with illicit drug consumption, and Rastas being the subject of scrutiny by the authorities. This is further exacerbated by the ignorance surrounding their choice of hairstyle that contributes to fuelling a prejudice resulting in their social isolation as an outcast community.

‘Wrap Collection Volume 1; Rasta Voice; #26 Issue no. 95 May 1986’ (n.d.), Archives Unbound, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/SC5110287229/GDCS.GRC?u=ucl_ttda&sid=bookmark-GDCS.GRC&xid=b0b19bef&pg=21

A Religion Under Attack

Historically, the Dangerous Drug Act in Jamaica has resulted in inspiring a constant systematic attack on the Rasta community due to the restriction of cannabis. This is regardless of the national constitution’s declaration that citizens have the “Right to Freedom of Religion and Conscience.” The inflexibility surrounding these laws, which has only recently been addressed with amendments in 2015, has resulted in the social stigmatisation and exclusion of Rastas, despite the growing urgency of calls to protect the group’s rights and their developing international presence. Since 1996 the status of Rastafarianism as a religious system has been recognised by the UN and understood to be a distinct religious identity. “The Rastaman’s Right to Religion” (1997) is a valuable primary source, available through Gale Primary Sources, that introduced me to this struggle, in which Dr Dennis Forsythe’s thought-provoking article explores the injustice of the laws surrounding ganja. Although laws are created in order to promote the betterment of society, conversation is important to integrating and including the voices of minority groups.

The Rasta’s Place in a Decolonised Curriculum

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as a result of the global impact of the Black Lives Matter movement, societies across the western world have been challenged to rethink the way race-related topics and histories are presented, specifically in terms of decolonising the curriculum and advocating for a more pluralistic syllabus. As an ongoing phenomenon, the black experience has always been underrepresented and often disregarded so far as its importance in education, and is often highly controlled and regulated as an area of study. Traditional subject areas including Religious Education, Theology, History and Philosophy and Ethics would benefit from a wider range of modules to challenge the very normative structures which dominate the building blocks of our society, and introduce important new perspectives.

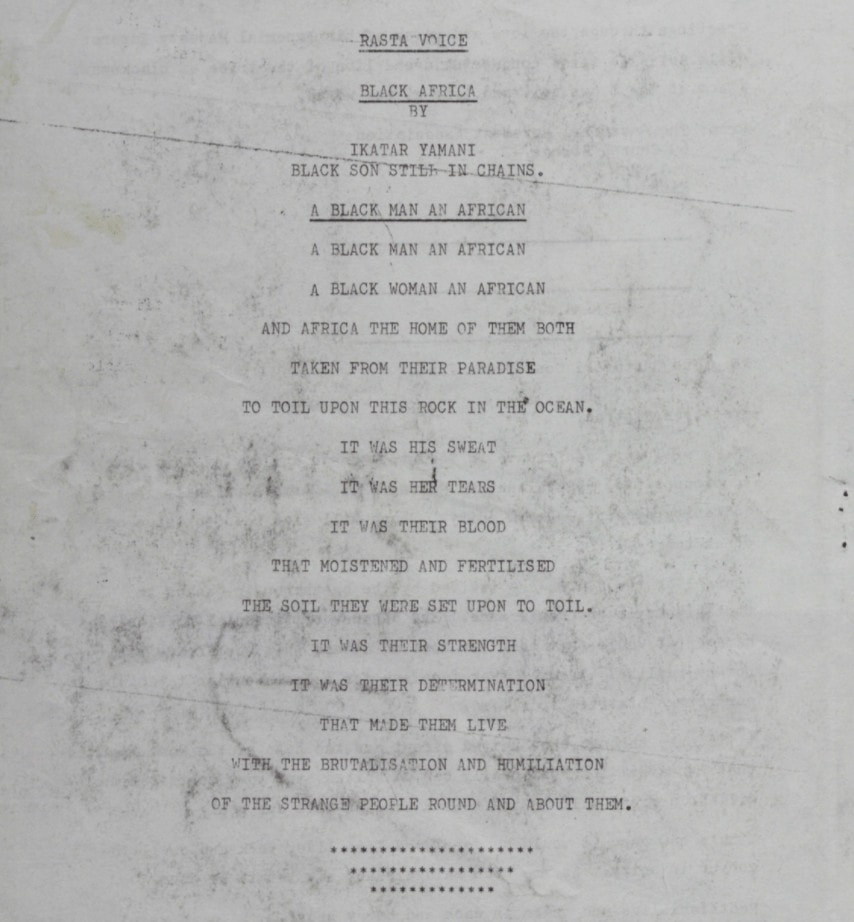

The esoteric knowledge preserved within the Rasta religion pertaining to the black experience is significant, similar to Vodou in Haiti, and Candomble in Brazil, which are also valuable areas of study. This is especially important in terms of eliminating stereotyping and racial bias, as often these religions are stigmatised and ridiculed due to a lack of knowledge. For instance, the primary source titled “Rasta Voice” that I came across in Gale Reference Complete highlights the Rasta voice and illuminates the puzzling complexities of navigating and approaching identity in the traumatic aftermath of slavery and subsequent black diaspora. The author Ikatar Yamani writes as a “black son still in chains” that a reoccurring idea present across Rastafari traditions is that, whilst rooted in slavery, the black struggle is no longer physical, but rather as an imprisonment of the mind in the context of the modern world.

A great deal more information on this topic and others can be found using Gale Reference Complete. Collections of primary sources such as these are crucial in unearthing these insightful and valuable voices.

‘Wrap Collection Volume 1; Rasta Voice; #23 May 1982’ (n.d.), Archives Unbound, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/SC5110287161/GDCS.GRC?u=ucl_ttda&sid=bookmark-GDCS.GRC&xid=3433e35b&pg=15

If you enjoyed reading about unearthing Rasta voices in the modern world, you might also like these other blog posts:

- Decolonising the Curriculum with Archives Unbound

- Beyond Notting Hill Carnival: Re-visiting the life of Claudia Jones

- Indentured Indian Workers and Anti-Colonial Resistance in the British Empire

Blog post cover image citation: Wrap Collection Volume 1; Rasta Voice; #20 No. 87* March 1978. N.d. Archives Unbound, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/SC5110287176/GDCS.GRC?u=ucl_ttda&sid=bookmark-GDCS.GRC&xid=a70bac6c&pg=1 combined with Wrap Collection Volume 6; Rasta Vibrations; #02 Fall 1994. N.d. Archives Unbound, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/SC5110289703/GDCS.GRC?u=ucl_ttda&sid=bookmark-GDCS.GRC&xid=9a823c15&pg=1