|By Lola Hylander, Gale Ambassador at University College London|

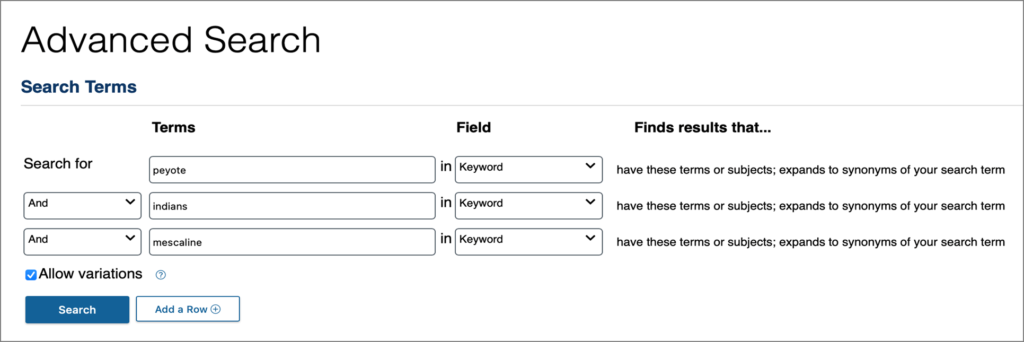

I am a student of the History and Politics of the Americas at University College London, and my dissertation will analyse Employment Division v. Smith (1990),a Supreme Court ruling that overturned almost a century of activism surrounding the Native American Church’s (NAC) right to practice peyotism, a religion based on the ceremonial use of the psychedelic cactus, peyote, in the United States. Religious debates largely define the discourse around peyote use, examining whether or not it should be protected under the First Amendment’s freedom of religion clause. Wanting to further understand the role of religion in the peyote debate, I turned to Gale’s Archives Unbound collection to see what I could find.

The Women’s Missionary Advocate

I used the Advance Search feature on the Gale platform, simultaneously inputting ‘peyote’, ‘Indians’ and ‘mescaline’ – the protoalkaloid that gives peyote its psychedelic property.

From this search, I found a fascinating publication called the Women’s Missionary Advocate in the International Women’s Periodicals, 1786-1933: Social and Political Issues collection. Circulated between 1880 and 1910, the periodical contains correspondence between Christian missionaries, detailing their visits to reservations that aimed to mass-convert Natives to Catholicism. Although this was a post-colonial goal, conversion was also a prevalent theme of the colonisation of the Americas and the Spanish Inquisition. When analysing the letters, I encountered religious motifs that have been used historically to attack indigenous traditions, including peyote use, pointing me closer to an answer about the role religion played in the debate.

Peyote as inhibiting Christianisation

Throughout the periodicals, peyote is consistently referenced in relation to the devil, and described as a factor preventing conversion to Christianity. An 1894 issue of the publication chronicles how ‘the devil multiplies forces and increases efforts to stay the work of Christianity in this field’ through peyote. Four years later, a letter written by a missionary in Oklahoma described peyote as ‘just one of the devil’s clever counterfeits of religion,’ that can ‘shut them off from the true.’

![Woman's Missionary Advocate, [Volume 19, Issue 2], August, 1898. Archives Unbound,](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Devils-clever-counterfeits.jpg)

These quotes speak to a fear of Native tradition, and the belief that suppression of these ‘savage’ traditions was seen as necessary to ‘save’ the Natives from evil. Peyote, referred to in the periodicals as ‘mescal’ – not to be confused with the agave beverage – was feared to cloud the mind with evil, preventing Natives from becoming ‘civilised’.

This source references a debate over whether or not peyote is compatible with Christianity (specifically Catholicism). Indeed, historians have drawn parallels between peyotism and the Eucharist: partakers will fast before both ceremonies, and mutter prayers while chewing; both ceremonies are perfumed, with copal in peyote ceremonies and frankincense during the Eucharist; peyote is thought of as the flesh of a deity, and the bread in the Eucharist represents the body of Christ.

Yet, missionaries disagreed on whether or not this comparison was in bad faith. One missionary spoke of a priest who ‘teaches them that… all they need to do is come to him to be baptised into the Catholic Church, and they can go on worshipping the mescal,’ implying that peyotism is compatible with Christianity. Yet, an 1896 issue details an interaction with a Christian Indian who said that through peyote, he expresses his love for Jesus. The missionary responds, ‘Jesus don’t pay attention to your prayers, because you go right on and do the bad things again.’

![Woman's Missionary Advocate, [Volume 16, Issue 8], February, 1896. Archives Unbound](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Jesus-dont-pay-attention-to-your-prayers.jpg)

When the Native American Church was formed, 22 years later, it mimicked the structure of the Christian Church, becoming an official religion protected under the First Amendment. Opponents argued that it was fictitious to recognise peyote as a religion, and yet, peyotists masterfully argued that the use of the cactus was no different than sacramental wine in Christianity.

Peyote as physically harmful

An 1894 issue of this periodical described peyote intoxication as ‘extremely hurtful to the Indians, mentally, physically, and morally,’ and the 1898 issue depicted above described peyote as ‘the intemperance of both the Kiowas and the Comanches,’ implying that it was consumed without limits, as a drug. The reduction of peyote to simply a drug in these statements overlooks its significance as a deity and an instrument of worship.

An earlier issue describes the aftermath of a ceremony with ‘four of the Indians under the stupefying influence of this false worship, which is cursing these Indians, both body and soul.’ These beliefs of the physical and mental harm to Natives served as justification for Christianisation.

Impacts today

Debates over the potential harms of peyote still play out today. One contemporary contradiction is the listing of mescaline and peyote as Schedule I substances in the 1971 Controlled Substances Act. This means that the drugs have high potential for abuse and cannot be used safely without medical supervision. However, there is an exemption for members of the NAC, who can prove membership to a federally recognised tribe and a blood quantum of at least 25% Native blood. Some historians argue that to consider peyote as a Schedule I substance and simultaneously allow NAC members to use it, logically infers that either the government believes that NAC bodies will not be physically harmed by the drug in the same way their white counterparts may be, due to inherent biological differences – a pseudoscientific stance disproved by modern genetic research – or that there are alternative but equally discriminatory and unjust reasons behind this governmental decision.

![oman's Missionary Advocate, [Volume 14, Issue 7], January, 1894. Archives Unbound](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/mescal-highlighted.jpg)

Peyote and other ‘sins’

Peyote is likened to other ‘sins’ throughout the periodical, playing into stereotypes about Native Americans and addiction. An 1898 issue repeatedly compares the ‘chaos’ created by peyote to alcoholism, claiming to have witnessed ‘a mother sip from the glass of “burning water” and then put it to the lips of the child in her arms,’ then describing how many Natives cannot be converted due to alcohol abuse. Not only does the alcoholic stereotype ignore the fact that alcoholism can be an issue in Native communities due to generational trauma from colonisation, these claims overlook the fact that peyotism is a healing process that allows many alcoholics to free themselves from addiction.

Another example is a comparison to gambling in an account of a mission in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The author speaks about how in the testimonies of converted Indians, ‘in enumerating their sins they always put mescal worship right in with gambling, horse racing, etc.’ Two months later, an issue likened the peyote ceremony to an orgy – a common post-colonial trope – claiming that ‘one experimenter reports that the symptoms in the early stages of the orgasm resembles those which precede some forms of insanity’ in ceremonies.

The religious nature of peyote persecution

With attitudes to freedom of religion ever-changing, the future of peyote use in the US is uncertain. What has been made clear through researching within these fascinating documents in Gale’s International Women’s Periodicals, 1786-1933: Social and Political Issues collection is the religious nature of peyote persecution, stemming from colonial beliefs surrounding Indigenous traditions and desires to suppress them by forced assimilation.

If you enjoyed reading about perceptions among Christian Missionaries of peyote use, check out:

- Indigenous populations: exploring early encounters, subjugation and protection

- Unearthing and decolonising the Rasta voice

- Occupying Alcatraz: the Native American experience then and now

- Marking Columbus’s first journey

- Discovering new points of view about European and Colonised women using the “Voice and Vision” archive”

Blog post cover image citation: ‘Woman’s Missionary Advocate, [Volume 16, Issue 8], February, 1896’ (1896), Feb, available: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/SC5105626310/GDSC?u=ucl_ttda&sid=bookmark-GDSC&xid=205521d0&pg=1