|By Rose O’Connor, Gale Ambassador at Maynooth University|

It might take readers by surprise that the History of Emotions is now described as a cutting-edge field of history. When I first discovered it, I asked the same question you may be asking now; do emotions have a history? Yet this research area has been garnering momentum in the last two decades, with scholars from all aspects of academia – from cognitive psychologists to anthropologists – contributing. And no one yet knows how the History of Emotions will develop. Consequently, there is so much room for investigation and innovation. Let’s look at some of the tools we can use in Gale Primary Sources to help us investigate this exciting aspect of history and how it can bolster your own research.

Where to Start?

The archive I will focus on here is Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) due to its broad scope not only in the early modern period, but entering the modern period also. To begin with, Gale’s Keyword Search is a great help; if you wish to search for an emotion like love, tens of thousands of results appear! However, if you wish to be more specific, you can dissect the emotion or its manifestations. You could explore, for example, specific types of love, and identify and track shifts within them. You can also refine your searches by date, which is vital for the history of emotions as we can see what emotions were being discussed, and how they were discussed, at different points in time, and in correlation to the prevailing context. Using Gale Primary Sources, users can access a large number of databases from one search bar which is convenient and helps students and researchers acquire and grasp different research angles faster.

Surprising Depictions of Patriotism

One of the most studied emotions is romantic love, not only across the centuries but across the globe. However, I wanted to investigate other manifestations of love. Within my own research, I am studying patriotic love, the love for one’s country, and examining the transition of this emotion from the early to late eighteenth century.

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, this is an emotion that many of us have grown up with and one which is even encouraged in society – by our families, friends, and communities as a whole. However, in contrast to what you may think, I would argue that this cultivation and the way we understand patriotism today is a relatively modern construct.

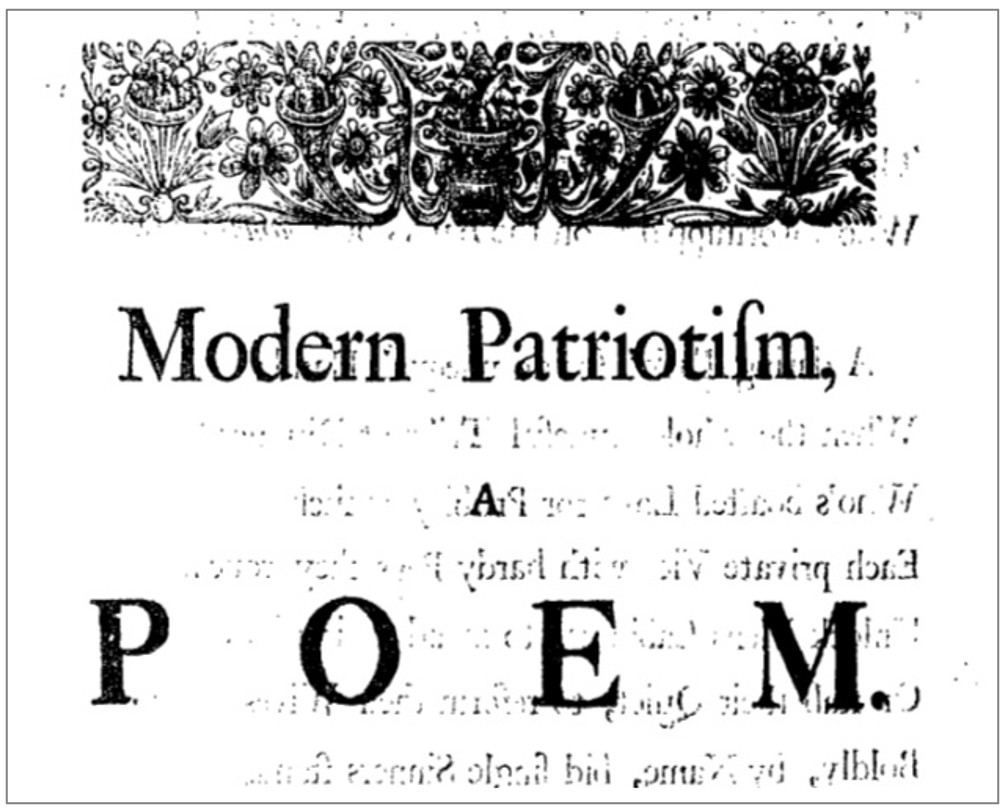

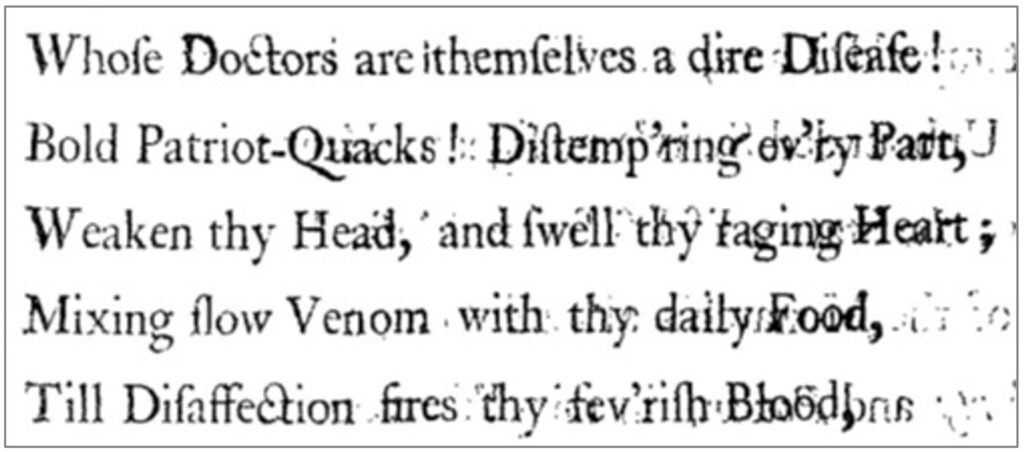

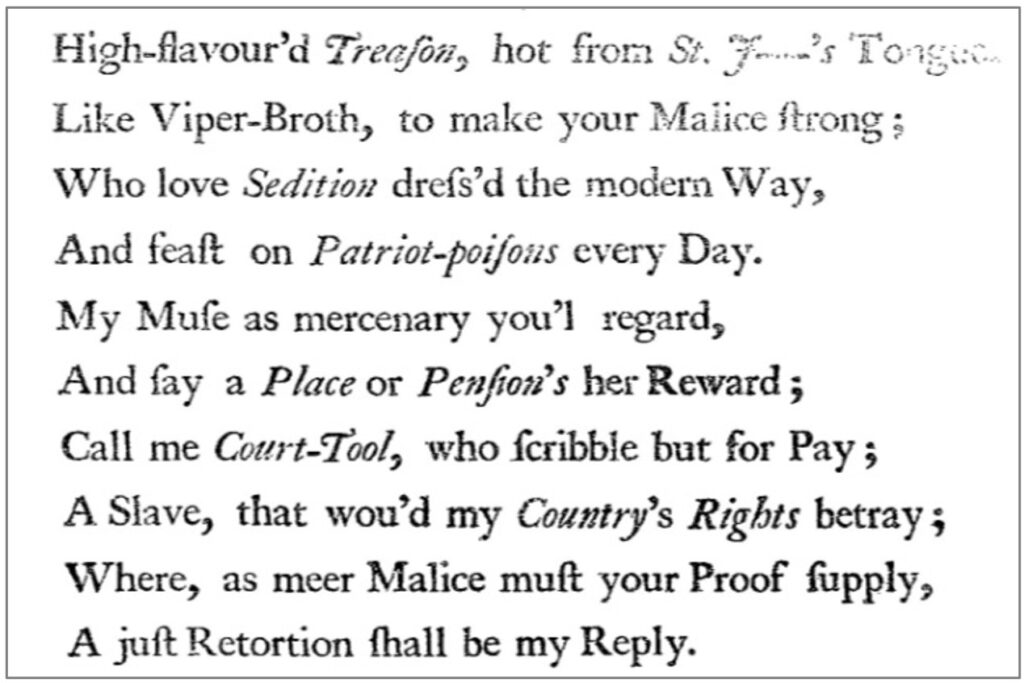

When looking for works about patriots and patriotic love, we are fortunate at my university to have a large number accessible to us through ECCO. When you start reading these texts, you can see that they are not discussing patriotism as a positive force of loving your country, but a negative one, and more of a political stance rather than the same type of love that we define as patriotism today. A great example is found in the poem below from 1734 titled ‘Modern Patriotism’ where the unnamed author berates patriots and those with similar sentiments as they go against the King. He spends about half of the 54-page poem berating patriots for being damaging to the kingdom which seems in contrast to our own understanding of patriotism today.

In the above paragraph, the author refers to ‘Bold Patriot-Quacks! Distempering every part, Weaken thy head, and swell thy raging heart.’ Comparing a patriot to a quack would be considered strange in the twenty-first century as it seems to indicate that they are a joke. And in the enlightenment, to be guided by ‘raging’ passions was a sign of weakness. We can see that during the early eighteenth century in England, loving your country was not considered the positive characteristic it is now, and in fact was considered damaging, as it challenged the love people should have for God and their King. We can see this in the same poem on the next page where it describes it to be ‘treason’:

Nothing Boring About Boredom!

Another avenue to study emotions is via analysing the changing use of language over time, and through this, when and why new emotions emerged – something made easier when using ECCO, where primary sources have clear bibliographic information. Thus, this digital archive not only helps us investigate the history of emotions, but also learn that there is nothing boring about boredom!

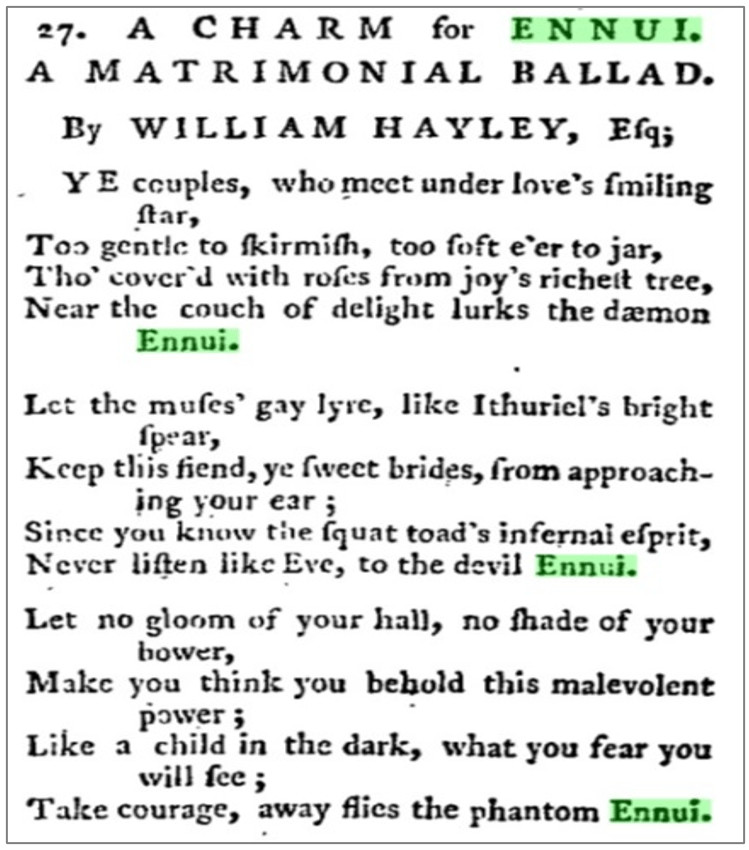

Before the late eighteenth century ‘boredom’ was not written or published anywhere. In contrast to other emotions like love, fear or hatred, when you search for ‘bored’ or ‘boredom’ on ECCO, the first writings about boredom or its variations such as bore as an emotion, or the French word ennui which was also used in English-language texts, did not appear until the late eighteenth century.

As you can see below, when you search for a keyword in Gale Primary Sources, it will highlight the word for you to easily focus in on the term within your chosen document.

So why was boredom – an emotion highly present in the twenty-first century – not documented until only three centuries ago? One argument about the rise of boredom is due to the Industrial Revolution and Georgian Period. This period saw the expansion of the middle classes, with increasing numbers pulled out of agrarian, subsistence lifestyles. As a part of this, there was an unprecedented growth in individuals with free time. Now, unlike ever before, these people had free time for leisure and with this newfound freedom, boredom arose.

Untapped potential in existing sources

These are just two examples of the practicality of investigating the history of emotions with primary sources. I do hope that you can apply this to your own studies as much as it has helped me with my own. At the very least I hope that it has piqued your interest in an area of history that you may not have considered before. The sources are there, and offer potential challenges to previously established interpretations in history. This room for innovation within this new area of history is extremely exciting and I’m keen to see what is to come.

If you enjoyed reading about the history of emotions and social history of the eighteenth century, check out:

- Exploring Early Modern Erotica and Social History in L’Enfer de la Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Researching and Teaching Women Writers Using Eighteenth Century Collections Online

- Teaching with Eighteenth Century Collections Online

- Fashion and the Eighteenth-Century Public Sphere: from Tatler to Twitter

- Etiquette and Advice, 1631-1969 – Good Manners as Prescribed by “Polite Society”

- Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens in the Eighteenth Century

Blog post cover image citation: Charles le Brun, The Expressions Trait é des Passions, 1732. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_le_Brun,_The_Expressions.jpg