│By Chris Houghton, Head of Digital Scholarship, Gale International│

Studying extremist groups has, sadly, never been more relevant or more important. Can text mining and data analysis be used to enhance this study, and potentially make discoveries that could help with the ongoing fight against political extremism? In this blog, I provide some suggestions of how scholars might benefit from utilising these research methods, by showing what can be uncovered by combining Gale’s Political Extremism and Radicalism archive with the Gale Digital Scholar Lab.

Using Radical Collections Workshop

In December 2020, I was asked to participate in a workshop entitled Using Radical Collections: Challenges and Opportunities, hosted by the Searchlight Archive at the University of Northampton. My fellow speakers were researchers and archivists from the most fascinating and challenging archives, including the Wiener Holocaust Library. Indeed, the Searchlight Archive itself firmly belongs in this category, comprising one of the major collections of material documenting the activities of British and International fascist and racist organisations.

Participating in unique events like this grants me the opportunity to dive into areas of the Gale primary source collections that I don’t frequent very often, and most importantly, view them through the lens of my day job – digital scholarship, digital humanities and text and data mining. My primary focus was the Political Extremism and Radicalism archive, a compilation of rare and unique archival collections covering a wide range of fringe political movements, from the far left to the far right.

The challenges of presenting and contextualising sensitive material

There are many pieces written about the challenges of presenting, framing and contextualising extremely sensitive or disturbing material such as that contained in this archive. In short, there is huge value in not shying away from this material in a classroom or exhibition setting, but sensitive, inclusive access and context is crucial. This naturally presents challenges for publishers of this type of material – read how Gale addresses these challenges here and here.

The Index of Digital Humanities Conferences – finding a gap in research coverage

Tasked with presenting radical archival material outside of the traditional “close-reading” paradigm, one of the first places I visited when researching my talk was an extraordinarily useful tool: The Index of Digital Humanities Conferences. Developed by a team of researchers, this resource enables detailed searching of keywords, topics and titles of over 7,000 papers presented at what might broadly be termed “digital humanities events”, over the last 60 years. Although the developers are clear that this is not a complete resource, it is the best resource of which I’m aware for exploring the subjects researched in digital humanities during that period.

To understand how much digital humanities research has been attempted on topics that might require a radical archive, I first downloaded the list of assigned topics. Going through this list turned up nothing that I would readily associate with this kind of research, so I switched to the Keywords list – a few words that a scholar or organiser would have assigned to a talk to better classify it. This generated scarcely better results, with the keyword phrase “Hate Speech” generating one paper, “Extreme Speech” three papers and “Racial Violence” one paper. The “Hate Speech” paper was also one of the “Extreme Speech” papers, so really, I had four papers, out of 7,113. Lastly, and to give myself the best chance of finding something, I used the full text search, searching every aspect of papers, from full text (where available), to title. Searching for racism or extremism or radicalism or “hate speech” or “extreme speech” netted a more respectable 92 results, although when I examined them, few actually applied to the subject, featuring titles including; “Quantifying narrative perspective in Ancient Greek: Narrator language and character language in Thucydides” and “The Logic of Kanji Lookup in a Japanese <-> English Hyperdictionary”.

These results certainly suggest that the study of political extremism and radicalism has, up to this point, been mainly conducted in a traditional academic manner, and hasn’t yet widely embraced techniques such as text and data mining and big data analysis.

Excitingly, this suggests a wealth of opportunity. With the widening availability of archives like Gale’s Political Extremism and Radicalism, and the availability of their underlying data for text and data mining through platforms like Gale Digital Scholar Lab, researchers working in this area have an unprecedented opportunity to explore this material in completely new ways and make discoveries that will propel the subject forward.

Analysis within Political Extremism and Radicalism

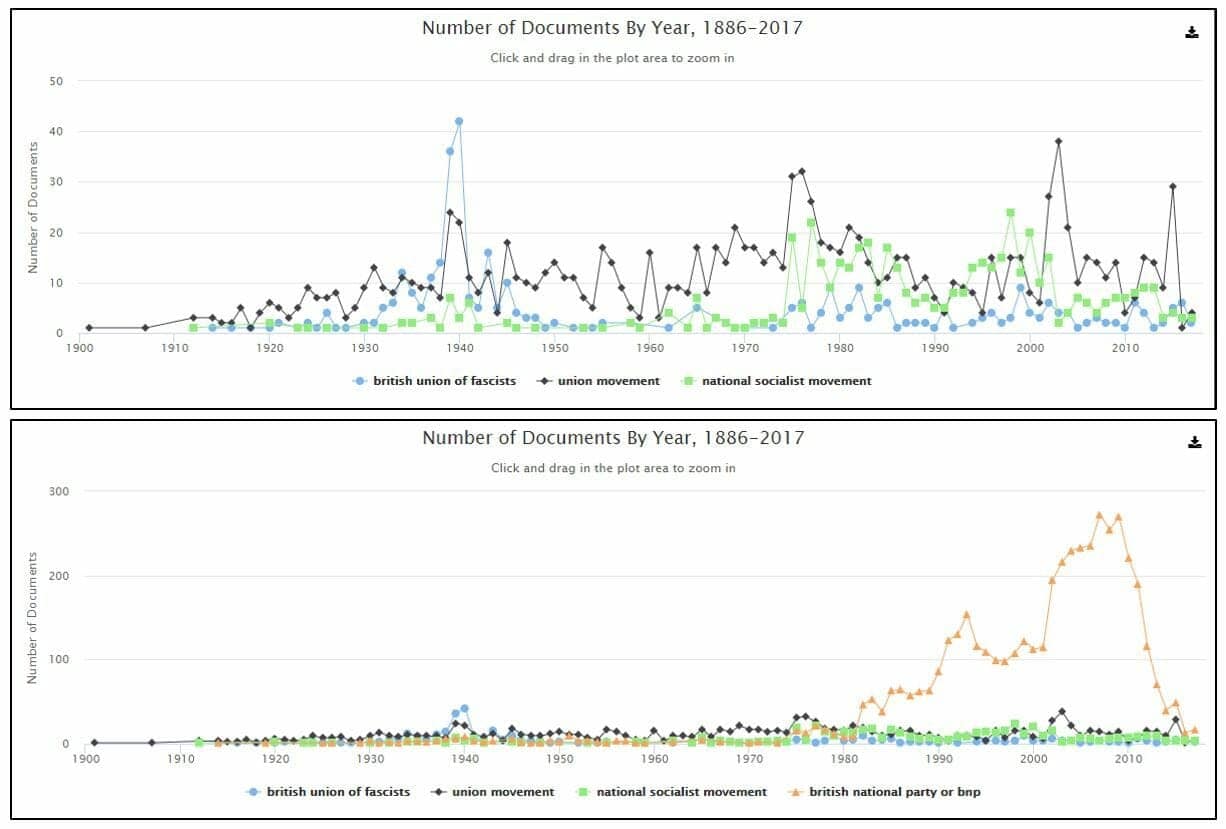

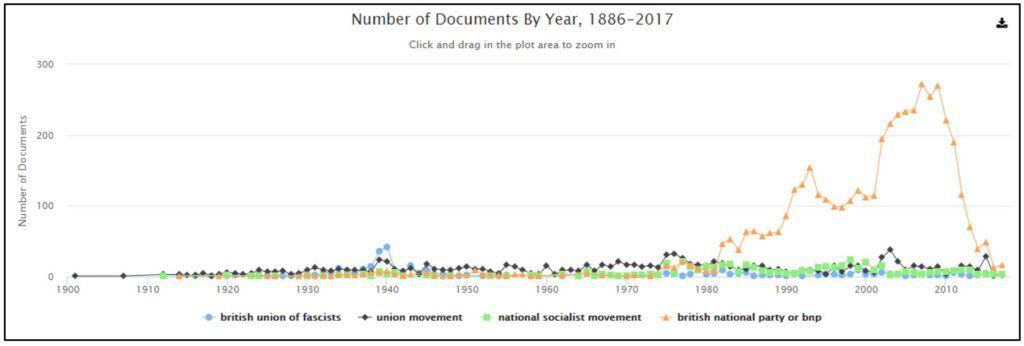

I went straight from the discovery that political extremism was relatively under-studied in digital humanities to the archives themselves. To begin with, I wanted to take a broad view of Political Extremism and Radicalism and use the integrated Term Frequency tool to track the mentions of various British far-right and fascist organisations. Firstly, I plotted occurrences of the phrases “British Union of Fascists” (Oswald Mosley’s fascist political party), “Union Movement” (the successor to the British Union of Fascists) and “National Socialist Movement” (a 1960’s UK neo-nazi group):

As we can see, this chart shows the story of the rise and fall of these various organisations and suggests peaks and troughs of their popularity and notoriety, at least within the archive.

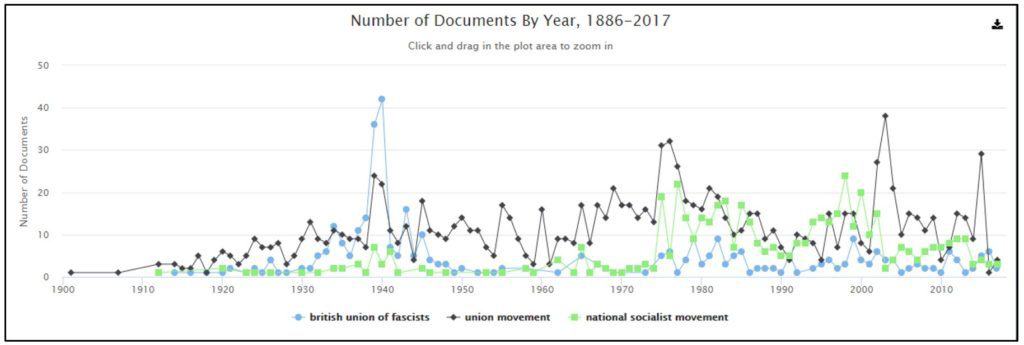

To provide context, a further term can be added to the chart, and I plotted “British National Party or BNP” alongside the previous terms:

The result is stark, as we can see mentions of the BNP slowly overtaking its far-right predecessors and eventually dwarfing them.

Deeper analysis with Gale Digital Scholar Lab

From analysing documents at scale within the archive itself, I moved to using Gale Digital Scholar Lab to start uncovering the themes contained in the archive. As with many such projects, I went into the Lab with some questions and hypotheses and was prepared to experiment and iterate to put these to the test.

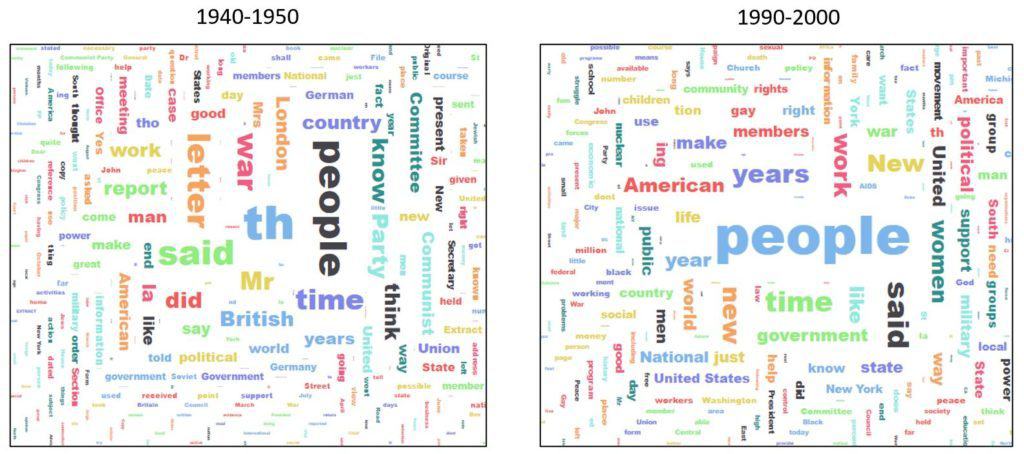

Firstly, I wanted to explore how the themes within Political Extremism and Radicalism had changed over time. By using the Ngram tool within the Lab, I could easily extract and visualise the most commonly occurring words and phrases in two decades, the 1940’s and 1990’s:

Unsurprisingly, some of the most common words in the 1940’s include: German, Communist, Soviet, Military and War. In the 1990’s, you are much more likely to find references to Gay, Rights, Black, Women and Nuclear, reflecting the struggles and conflicts of the age.

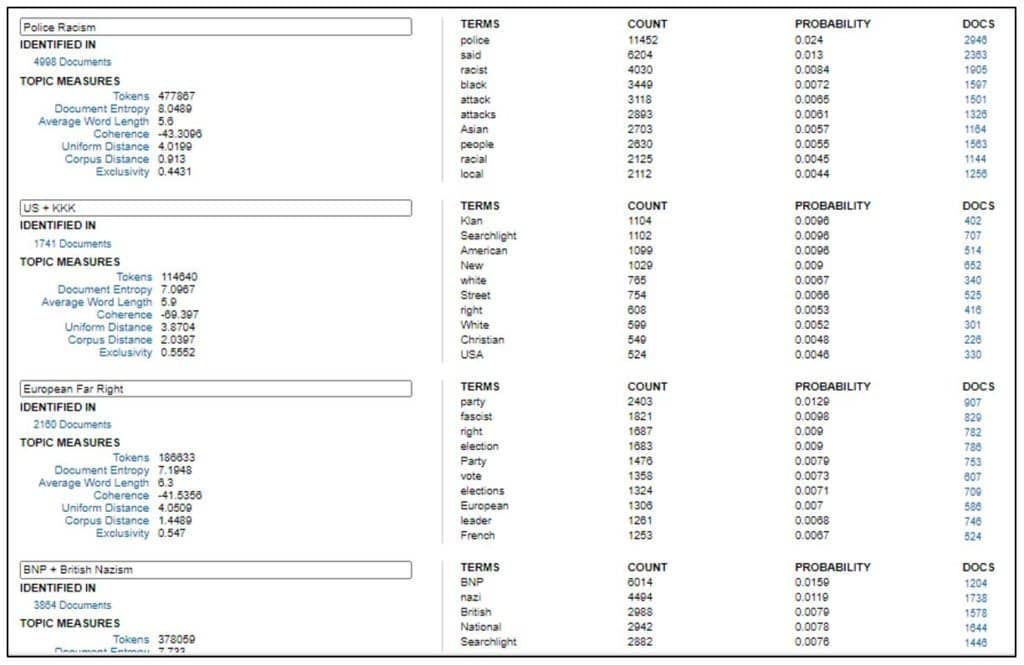

Having tested that hypothesis, the next step was to dig further into one of the collections within Political Extremism and Radicalism, the Searchlight Archive itself. Given the previous prevalence of mentions of the BNP in the latter half of the twentieth century, I concentrated on the period 1970-2000, using the Topic Modelling tool in the Lab to identify the most commonly occurring themes within the 9,472 documents from those thirty years:

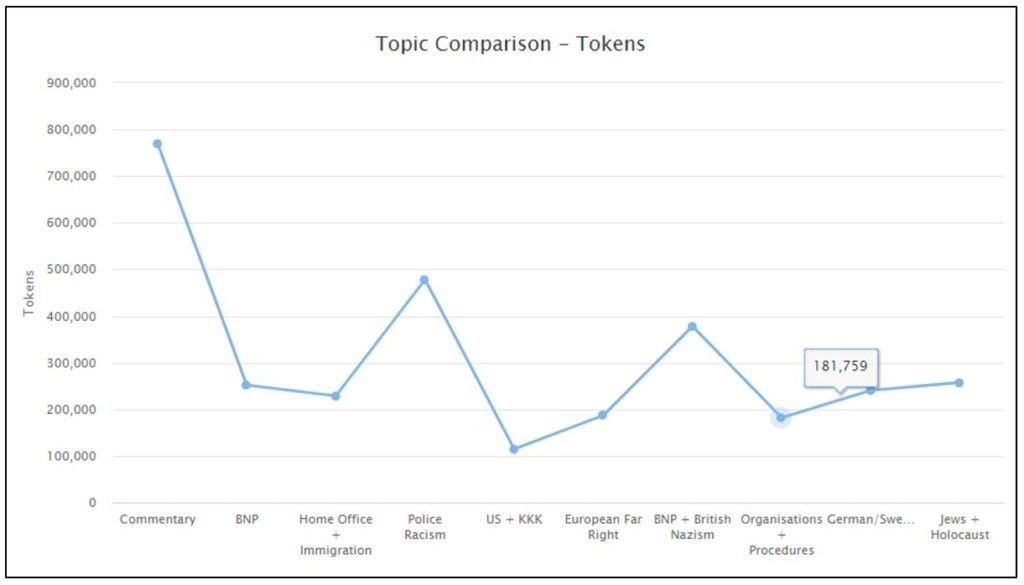

Topic Modelling is an ideal method to apply when you want to understand the “shape” of a collection, especially if you want to identify avenues for further study. After taking some time to classify the topics that had been identified, I was able to investigate the relationship between them, including which ones contained the most “tokens” (words):

For a researcher with limited experience in the archive or the subject, tools such as these in Gale Digital Scholar Lab – that require no prior coding experience – are an invaluable way of investigating a collection on a macro level, as opposed to exploring it document by document.

Macro analysis of archives like Political Extremism and Radicalism in the future

To conclude my presentation at the “Using Radical Collections” workshop, I wanted to issue a challenge to the researchers and academics in attendance. Given:

a) the lack of DH scholarship in this area

b) the increasing availability and access to DH methods through tools like Gale Digital Scholar Lab

c) the absolute relevance of these subjects to the modern world

Could they start to conduct more large-scale analysis of archives like Political Extremism and Radicalism?

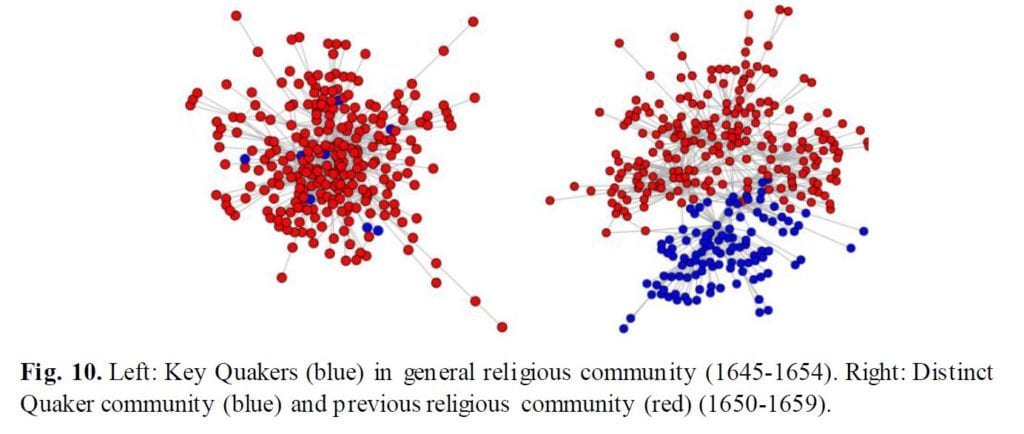

An area that is increasingly interesting to me is the algorithmic construction of networks to identify communities and influences within specific groups. As an example of this, researchers could look to the work of scholars like Hill, Vaara, Säily, Lahti & Tolonen who have identified shifting relationships in seventeenth century religious communities using network analysis:

Combining methods like this with analytical methods like Named Entity Recognition (available in the Lab), which allows the researcher to identify and extract “entities,” including people, geography or event, suggests the possibility of uncovering extremist networks from material like the Searchlight archive, and further expanding our understanding of a subject that is, regrettably, ever more relevant.

If you want to read more about Gale’s Political Extremism and Radicalism archive, check out the Acquisition Editor’s piece Political Extremism and Radicalism Archive: Why create it and why is it important now more than ever? or Inside the BNP: Being a Mole in the British Far-Right.

To read more about the complex and often sensitive process of building a digital archive, check out our Building an Archive series: The Role of Privacy and Content Breadth or The Role of Relevance and Research Trends when building a digital archive.

Or for more about the Gale Digital Scholar Lab, try: Lifting the lid on how we created the Gale Digital Scholar Lab or New Learning Center added to the Gale Digital Scholar Lab.