│By Ellen Grace Lesser, Gale Ambassador at the University of Exeter│

Studying a Humanities or Social Sciences subject might seem almost entirely focused on coursework, essays and, of course, the dissertation, but we are not entirely free from exams. At university level you are not “taught to the test,” meaning exams are more sophisticated than just regurgitating everything you’ve learned that term. You may end up feeling a little lost when revising for your exams, but there is hope! Not only have your lecturers taken every care to prepare you, you might find some helpful resources among online primary sources. Read on to find out more!

Different types of exam question

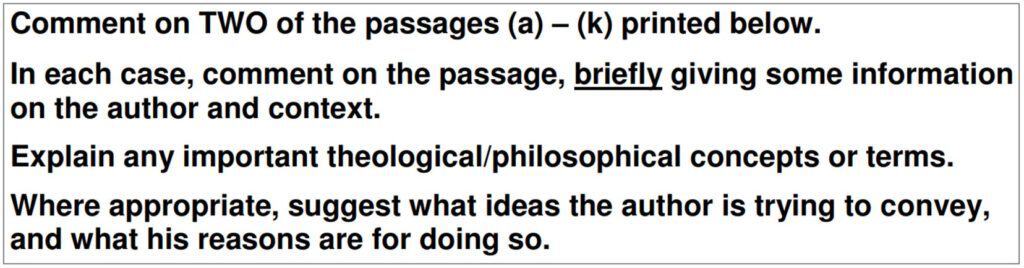

Almost to the point of parody, Humanities or Social Science exam questions follow the structure of “Discuss X claim”. You’re expected to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the claim, followed by presenting your own views of said claim. But what about questions that aren’t structured like that? Indeed, you might have an entire exam without any questions like that! When I was an undergraduate, I took a fascinating module called “Encounters in Philosophy and Theology” which was assessed with both an essay and an exam. The exam did not have any “Discuss X claim” questions – it looked like this:

How might one go about answering such a question?

Obviously, your lecturers will not leave you in the dark. All the texts and authors will have been covered throughout the module and if you’ve been making detailed notes and completing the assigned reading you will be able to have a stab at the question.

But, how might primary sources help?

The authors of the passages in this Theology exam span hundreds of years of thought. You know what else spans hundreds of years of thought? Gale’s archives! If a figure is important enough in the history of your discipline to warrant inclusion in an undergrad module, then the likelihood is that they will have been significant enough during their lifetime or subsequently to have attracted the attention of other thinkers whose work may have ended up the archive.

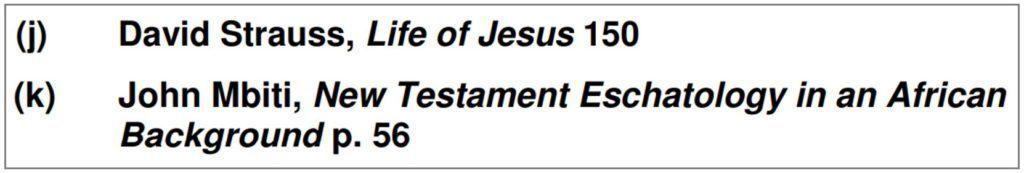

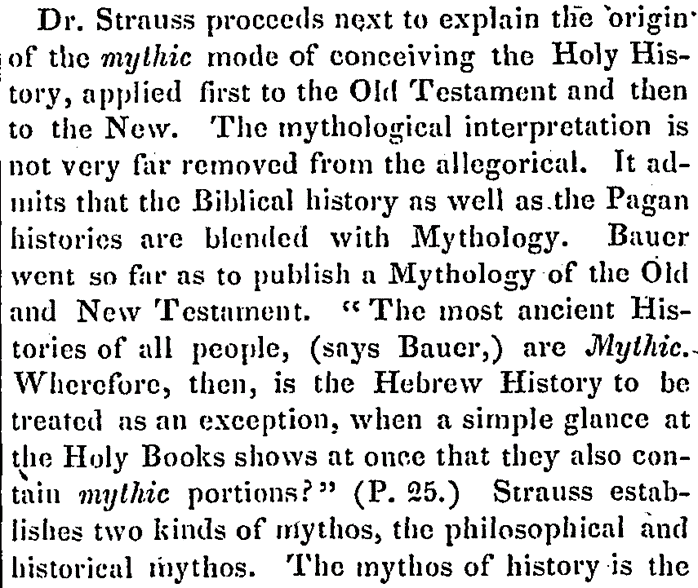

For this particular exam, we are being asked to look at two passages: two books, two authors. Let’s look at passages (j) and (k).

David Strauss

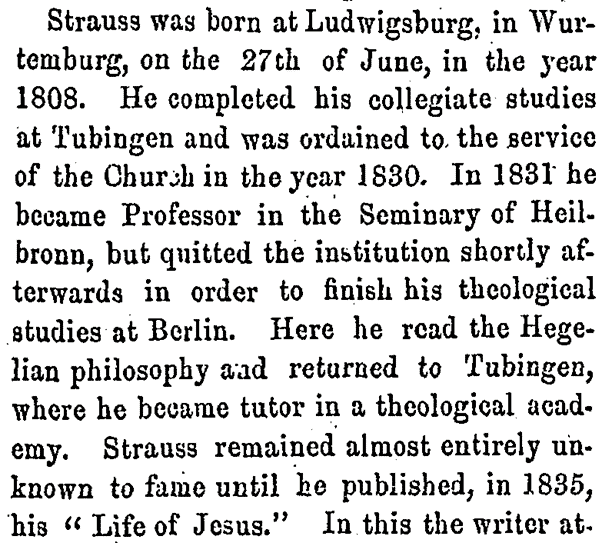

I was surprised, considering he was not American, to find that Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers has a wealth of information about David Strauss. You never know what you’re going to find in the archives, so prepare yourself for surprises whenever you press the search button!

But how do these sources help us with our exam question?

We’re asked to comment on the context of the passage. We might comment on Strauss as a person and his life, or the world in which contemporary, or later, readers of the text lived. A useful source to find out this kind of information would be a reflective piece on Strauss’ life and work. An obituary, perhaps.

In this source, which was only one of several obituaries for David Strauss that I discovered in Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, we are given the professional and theological context of Strauss’ life and, as the article continues, a review (of sorts) of the very text on which we are being asked to comment in our exam question. So incorporating sources such as these into your revision might just bump up your grade!

We are also asked for details about the argument present in the passage, and for explanations of theological ideas. While the above obituary provides a review of the text in question published after Strauss’ death, we can also find reviews of the text which were published shortly after Strauss’ book itself was published.

Sources such as these can speak to a different level of context than obituaries of the text’s author: they can speak to the academic context. What “gap” was Strauss trying to fill? How was he building on what had come before him? This article, so long that it was spread over two issues of the Boston Investigator in 1843, gives exactly that kind of detail.

John Mbiti

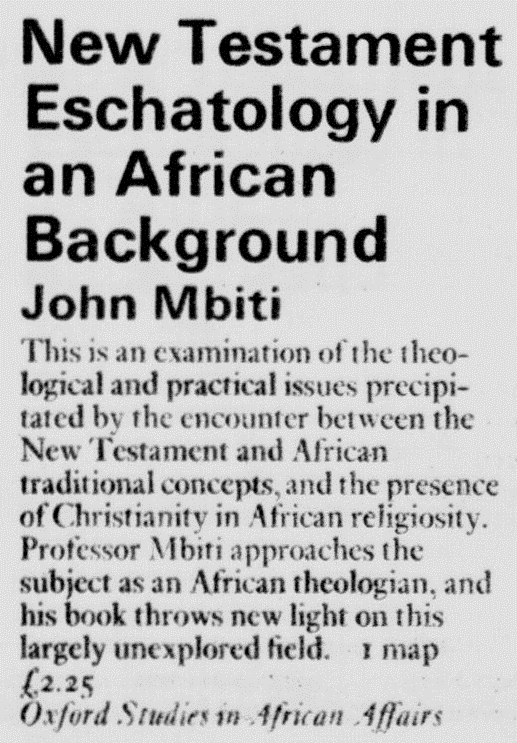

The archives are not just useful for answering questions about nineteenth century thinkers, though. Our second passage is by John Mbiti, from a book published in the early 1970s. As such, the kinds of places where we can find useful sources differs from where we found sources about Strauss. But this can be telling in and of itself. One place we can find contemporary responses to the book is among the thousands of reviews and blurbs in The Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive.

Sources such as that below take on a different style than the articles in the Boston Investigator. It comes from a page of the TLS which covers several books in a way intended to sell them. Only the most important details about each book can be given: what key content does the book cover? What will the reader “get out of” reading it? What is the author arguing? This brief summary is useful – giving us a handle on Mbiti’s overall argument it allows us to understand how the passage in the exam paper fits within the author’s overall argument.

Another aspect which can help us analyse a passage of text is understanding the target audience. How might we come to understand the target audience and appreciate how they were responding? We can look in the archives to find where the book was being discussed when it was first published! Whilst others may also have read the book, such reviews and discussion provide us with a snapshot of the readership.

We can again find discussions of Mbiti’s book in The Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive which speak to how the book was received shortly after its publication, including how the perception of this particular book compares to the reception of Mbiti’s other work:

So, whilst you might be used to diving into archives when writing an essay or dissertation – don’t forget about the archives when preparing for exams! From giving you a greater understanding of how a particular figure thinks to assessing the contemporary and subsequent reception of their work, the treasure trove of primary sources in Gale’s archives can be just as useful to exam preparation. Next time you’re revising, think about having a look in the archives – we bet you’ll find something useful!

With thanks to Dr Jonathan Hill at the University of Exeter for his permission to use his exam paper in this blog post.

If you enjoyed reading Ellen’s revision tips, check out her equally useful shortcuts to tackling complex academic works, or if you want to hear from a lecturer try How To Handle Primary Source Archives – University Lecturer’s Top Tips.

For more about how Gale Primary Sources can be used to explore the reception and reviews of academic arguments, try The Roots of ‘Ecocriticism’: Exploring the Impact of Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’.

Blog post cover image citation: Image from @windows on Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/photos/v94mlgvsza4