│By David Rosson, Doctoral Researcher at the University of Helsinki│

A big-picture goal for the Computational History research group at the University of Helsinki is to develop methods for studying how ideas spread during the Age of Enlightenment. This was a time period marked by notable thinkers and burgeoning ideas about reason, science, human nature, the state, and society as a system operating on certain principles. These ideas have profoundly shaped the modern world we live in today and in many ways still bear influence on current affairs.

An indispensable resource for studying historical discourse in this period is Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO), which covers a considerable portion of books published in Britain between 1700 and 1800. Our research group has been working with the datasets and building research infrastructure on top of Gale’s primary sources for more than a decade. One of the latest examples of our researcher-oriented tools is a web interface, Reception Reader, that helps with the tasks of exploring text reuse patterns in ECCO documents.1

Textual Reuse as a Window into Intellectual History

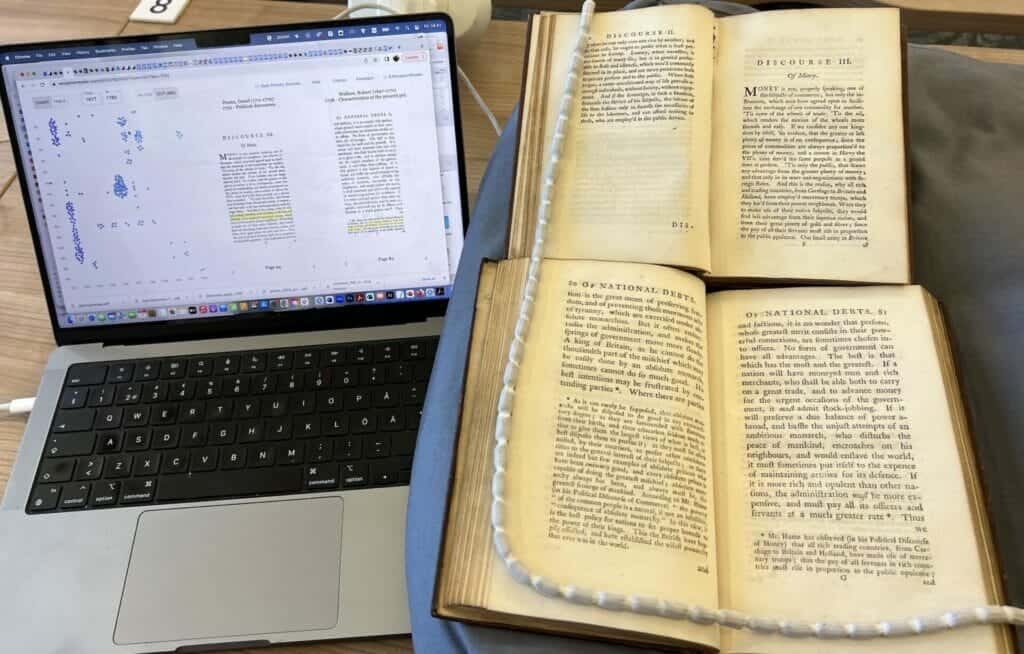

When you go to a prestigious library and dig up some valuable old books, you might find on these pages David Hume said something about fiscal policy, then, in a later book, another author is quoting Hume’s words and making references to his observations and opinions. This is quite exciting, because it’s as if you were witnessing philosophers who are now long dead having a discussion in the past, and you are looking at the direct evidence of that interaction.

Photo credit: taken by Mikko Tolonen while visiting the National Library of Scotland.

Not everyone is afforded the great fortune of being able to access these libraries and books. In Umberto Eco’s days a scholar would have to physically travel there, no less. Now, thanks to the internet and Gale Primary Sources, you can have it all from the comfort of your laptop.

But wait, there is more! Tracing historical discourse by going through thousands of books, flipping through the pages and eyeballing for overlapping pieces of text, such as quotes, to establish links and patterns of reception is extremely laborious work, if not impossible. The wonders of computing are changing that too.

The Computational History research group at the University of Helsinki found a modified version of the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) algorithm2 – a technique originally designed for comparing protein sequences – to be a much more error-resilient way of detecting textual overlaps compared to conventional string-matching methods, and applied it to the OCR text corpus of the ECCO documents. This allowed us to extract a reasonably exhaustive extent of all the links between text in such a vast number of books.

The Reception Reader tool: Reception Visualised Across Time and Pages

Given a book of interest, the Reception Reader tool can list and show the hundreds, even thousands, of connections fanning out from that book after the year of publication, to see how later authors are reusing its text segments. Conversely, you can also see the incoming connections from earlier publications as sources that influenced the book in question.

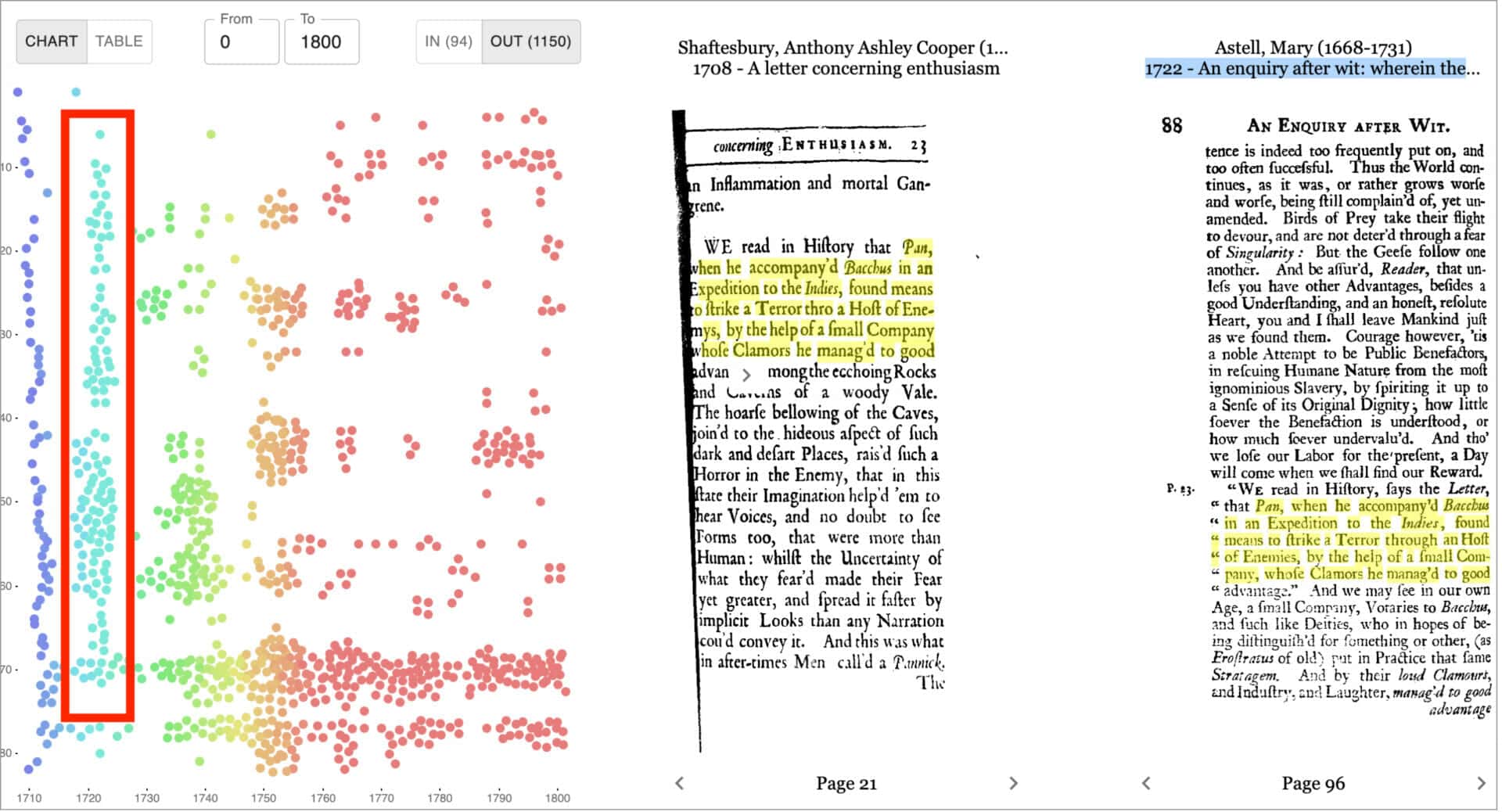

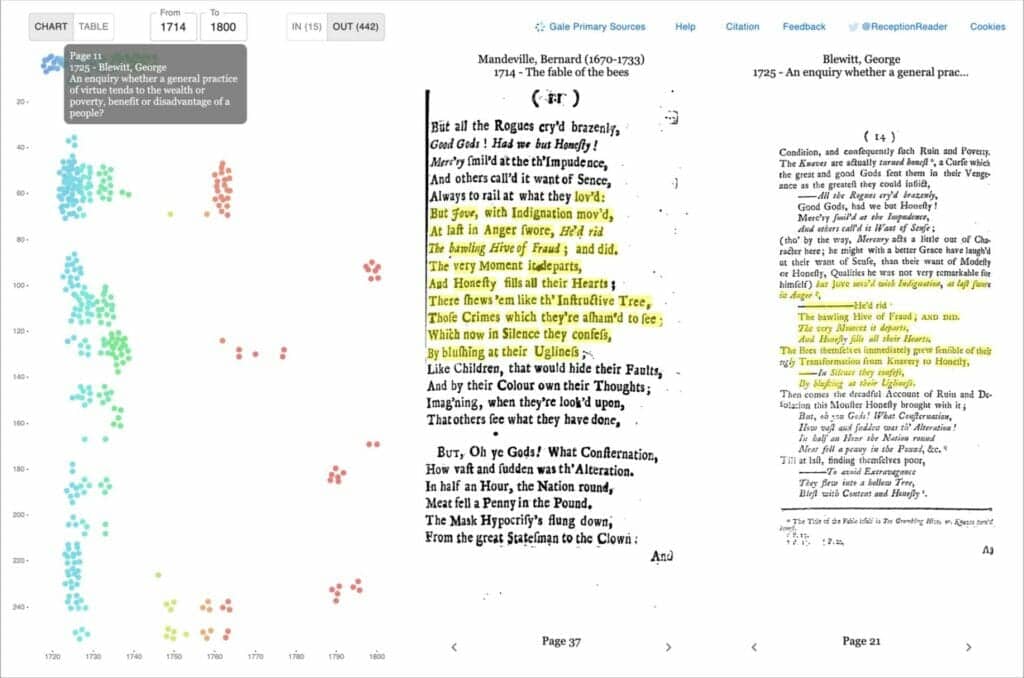

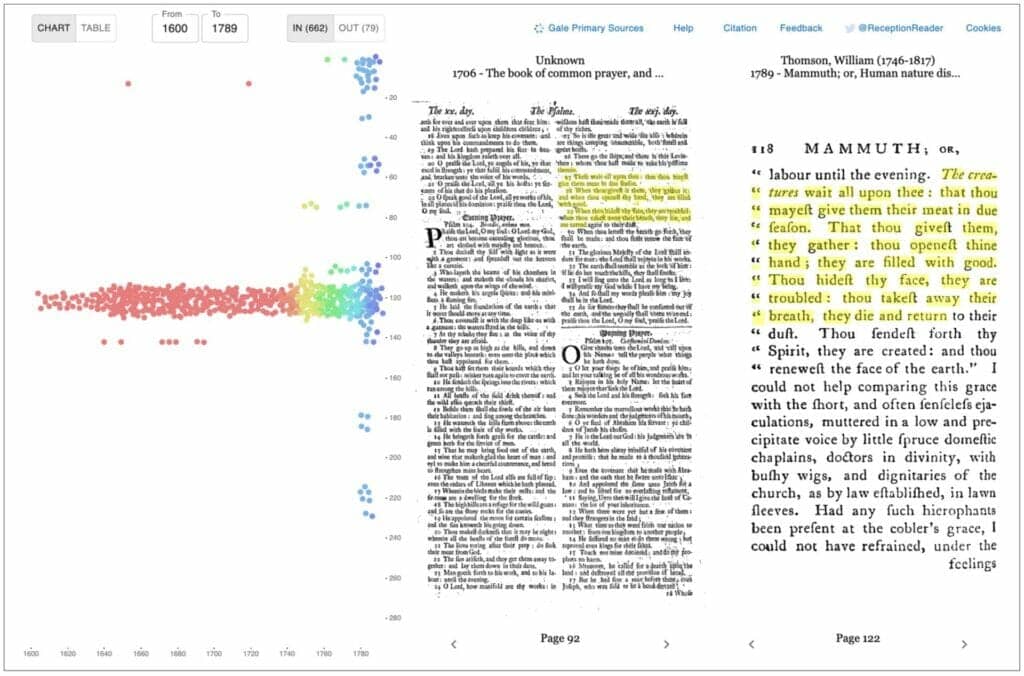

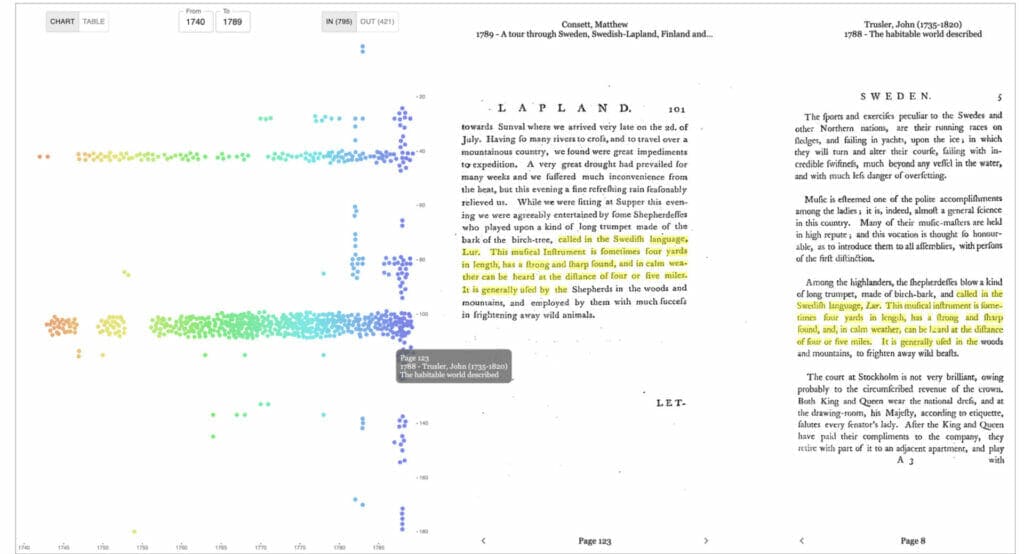

The visualisation above shows the reuse connections as a bee-swarm chart, as displayed in our Reception Reader tool. Each instance of text reuse (highlighted) is represented by a dot, arranged by location (page number in the source document) along the Y-axis, and by publication year (also reflected by the dot’s colour) of the destination document on the X-axis.

From the overall patterns, we can try to spot which parts of the book were most talked about, and when. By hovering over a dot, we can see the details of “who” was talking about that section of the book. Clicking on a dot brings up the reuse context – shown on the right in the above picture. Again, thanks to Gale’s archive collections we can also see the scanned images of the pages. This context allows researchers to switch from “distance reading” of looking at the patterns to “close reading” of examining the reused text and its surrounding nuances.

Dialogues, Arguments, and Clichés

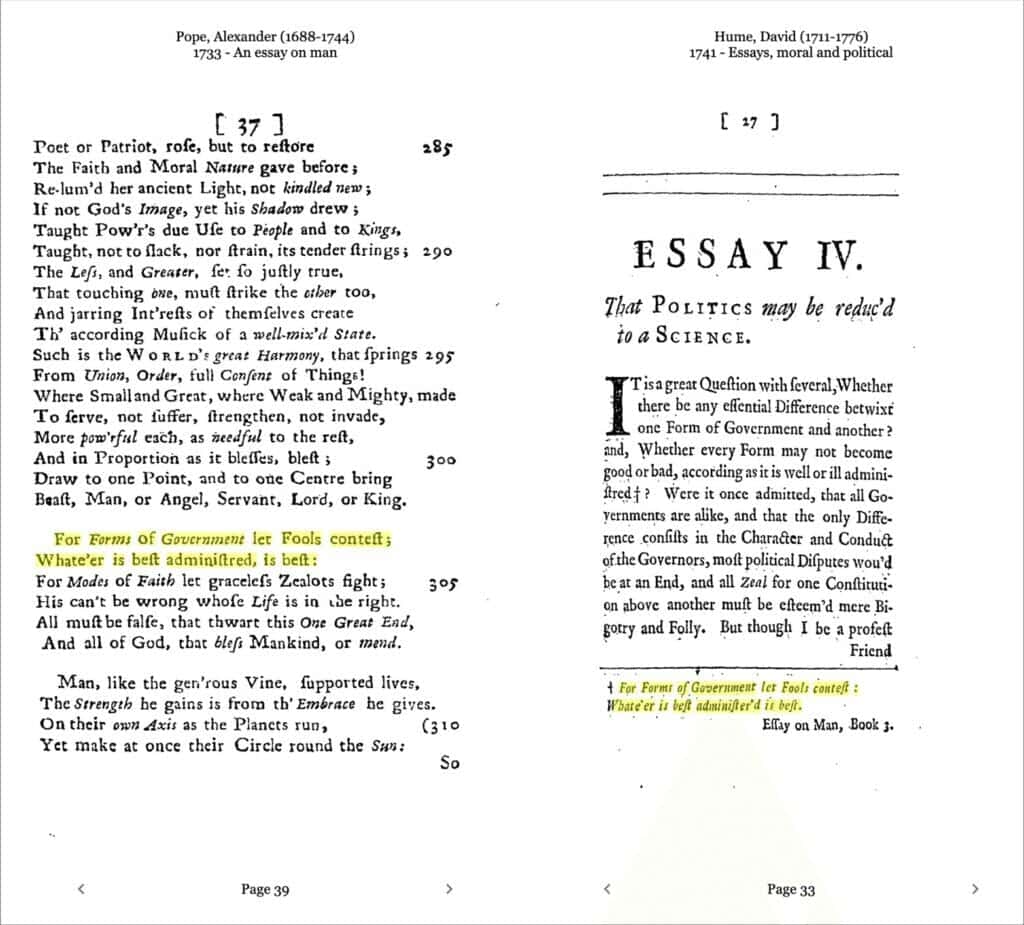

Isn’t it a delight to see how famous authors were quoting each other, as if they were having a contemporary conversation?

Or, it may also pique your interest to see how they were critical of each other, as it was common at the time to use full quotes when criticising another author’s ideas. Often one can find a book that critiques through the whole length of an earlier book.

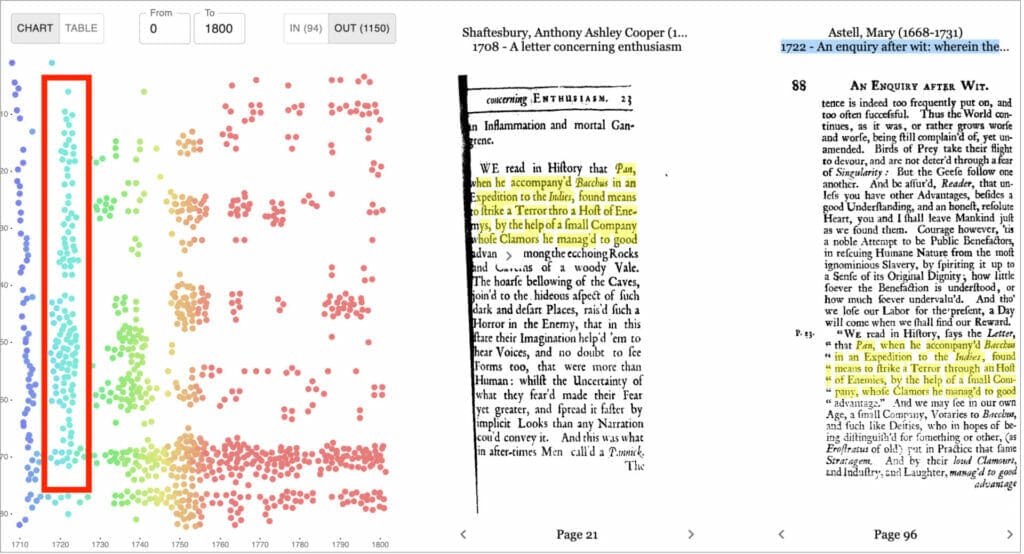

overlaps with Astell’s An Enquiry After Wit highlighted by a red box.

Then, there were some passages that were everyone’s favourite, and got quoted over and over throughout the ages, which can be seen in the pattern of a long, stretched-out horizontal band. In the picture below, the utopian author William Thomson quotes a psalm that was found in popular prayer books.3

The dataset of the Reception Reader features a good 961 million connections between passages, so there’s plenty to explore!

Research Questions and Text Reuse Cases

The Reception Reader is very versatile. How it helps with exploration very much depends on your specific research interests: you can use it to gauge the reception history of a specific work; you can use it to examine unattributed reuse as fresh evidence for authorship; you can use it to study editions and reprints.

Here are some examples of the types of reuse and what questions they can help answer:

• Quotes (e.g. Latin, biblical, famous quotes) What was the process of quotes from Lucretius becoming epigraphs over time?

• Reprints of longer passages (reused sections from essays or treatises appearing in works by different authors) What was the distribution of Hume’s essays outside of his published works?

• Modified reuse (how a specific work was received by later works) How did Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion feature in other historical works?

• Verse reprints (e.g. reuse of poetry in unexpected or uncommon locations) How did Dryden’s poetry spread outside of known collections?

• Unattributed reuse (hidden or obscured reuse of texts) Can we gain a broader understanding of the reception of Hume’s essays by exploring their use in other works without proper attribution?

• Artefacts (e.g. imprint of publisher, advertisement) What was the distribution pattern of advertising for Hume’s Treatise in printed books in the eighteenth century?

Try the Reception Reader to Explore Topics in Your Own Research Area!

To try out the Reception Reader for yourself, please visit https://www.receptionreader.com. We have also prepared an article which includes a brief guide on using the interface: https://doi.org/10.5334/johd.101.

The tool will probably prove more fun to use if you find a good fit for your research interest and specific research question. What we (the authors) are most interested in is to learn more about what users can do with the tool. We would love to gather feedback and incorporate new ideas into the future development of the Reception Reader and other research tools. Please feel encouraged to reach out and talk about your experiences using the contact details below!

Web: https://www.receptionreader.com/

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @ReceptionReader

This work has been funded by the Academy of Finland under Grants 1333716 and 1347706.

If you would like to read more about the ways Gale Primary Sources have been or can be used in Digital Humanities projects, try:

- Introducing My Students to Digital Humanities Research Techniques (also uses ECCO)

- The Author Gender Limiter Tool Brings Exciting Potential to the Study of Women’s Authorship and Digital Humanities

- Investigating the Evolution of Twenty-First Century Pop Culture Using Digital Humanities Techniques

- Can Digital Humanities teach us more about Political Extremism?

- Exploring Receptions of Classical Literature with The Times Digital Archive and Gale Digital Scholar Lab

Blog post cover image citation: Reception Reader showing reuses of Shaftesbury’s A Letter Concerning Enthusiasm; overlaps with Astell’s An Enquiry After Wit highlighted by a red box.

- Tolonen, M., Mäkelä, E., & Lahti, L. (2022). The Anatomy of Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO). Eighteenth-Century Studies 56(1), 95-123. https://doi.org/10.1353/ecs.2022.0060.

- Vesanto, A. (2019). Detecting and analyzing text reuse with BLAST. Pro Gradu-Tutkielma. https://www.utupub.fi/handle/10024/146706.

- Hinderks, K. S. (2023). Cromwell on the Moon; Or, Printing, Popularity, Persuasion: An Account of Text Reuse Patterns and Eighteenth-Century Utopian Thinking.