|By Ellen Boucher, Gale Ambassador at the University of Bristol|

One of my History modules this year, Outlaws, focused on the robbers, bandits and smugglers on the outskirts of society. For my final presentation for the module, I chose to study maritime wreckers using Gale’s Historical Newspapers, to explore how Daphne du Maurier’s novel Jamaica Inn, published in 1936, fitted into a changing narrative surrounding wreckers. ‘Wreckers’ was the name for those who would strip grounded or wrecked ships of valuable contents. Originally, they have been portrayed as dangerous criminals, in marked difference to other pirates and thieves we studied during this module, whose history has often been romanticised. Instead, wreckers, who were typically opportunists who saw themselves as having a right to the bounty from ships, were portrayed as dangerous and murderous criminals who would purposefully lure ships to wreck. This is the type of wrecker Daphne du Maurier presents in her antagonist, Joss Merlyn, a cruel and violent criminal.

My Outlaws Module Assessment

This presentation was probably my favourite of the assessments; the broad theme and narrated PowerPoint form allowed for a lot of creativity. It asked for a historical commentary on an object, place, person or event relevant to the theme of Outlaws. For this assessment, I chose to focus on the novel Jamaica Inn by Daphne Du Maurier, to examine the presentation of wreckers. Allegedly, wreckers purposefully crashed ships to steal their wares. The truth is more mundane; they tended to be coastal communities who collected anything salvageable from shipwrecks and then saw it as their right to keep this bounty. Wreckers were something of an outlier on this course; while pirates, smugglers and bandit have been romanticised within history, wreckers have been demonised. Using a literary text as well as newspapers allowed me to explore both the history of maritime wreckers, and their representation in culture, literature and legend.

Furthering the Myth of Murderous Criminals

In her book Cornish Wrecking, 1700-1860, Cathryn Pearce has shown that du Maurier’s novel and the film adaptation that followed were central to furthering the myths that portrayed wreckers as murderous criminals.1 Indeed, in the review below from 1995 of the audio version of Jamaica Inn, the reviewer (whilst disparaging of the abridged, audio version) strongly defends how great the power of the original novel to strike fear in the heart of the reader. ‘The drunken Joss Merlyn,’ the reviewer writes, ‘seemed the greatest villain I had ever come across’.

Widespread Views of the Barbarity of Wreckers

Du Maurier’s violently murderous character Joss Merlyn represents a myth that is also present in Gale’s newspaper archives. I put the key words ‘wreckers’ and ‘maritime’ into Gale’s Advanced Search and then filtered the search to newspapers and periodicals. The murderous reputation that wreckers had obtained was quickly obvious; a 1936 article in the Cornishman described historic Cornish ‘fisherfolk’ as ‘wreckers, murderers, barbarians, and treacherous.’ It goes on to define wreckers as ‘those men and women who deliberately lured ships to destruction by false signals and other means for their own material gain’ and says that they were guilty of ‘the vilest crimes against humanity’ such as allowing ‘a fainted brother to perish’ and ‘shoving the drowning man in the sea.’

The fact that the Cornishman, a local publication, published this opinion piece unsympathetic towards wreckers suggests that the myths about their murderous intent was widespread. Du Maurier’s terrifying characters are therefore unsurprising; Jamaica Inn influenced, but was also influenced by, the murderous reputation that wreckers had already obtained.

Roberts, Michele. “Embracing her inner tomboy.” Times, 28 Apr. 2007, p. 9[S3]. The Times Digital Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IF0503645553/GDCS?u=univbri&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=45b43dac

Reception of this Literary Portrayal

Using a literary text, Jamaica Inn, also meant I could explore how the representation of wreckers – in both the film and the original novel – has been received. Was it different to the expected portrayal? Did people enjoy reading about history’s rebels in this way? In 2006, Nick Rennison’s Sunday Times article attributes Jamaica Inn with bringing wreckers into the popular culture, referring to du Maurier’s text as a ‘historical novel’. This highlights a problem with the historiography of wreckers prior to the analysis contributed by historians like Cathryn Pearce and Bella Bathurst; people treated the novel as historically accurate.2 Rennisson echoes the definition of wreckers as ‘hard-hearted’, ‘luring unwary vessels on the rocks and then plundering them.’ It is unsurprising then, that du Maurier’s portrayal of wreckers is murderous and violent, with quotes such as ‘dead men tell no tales’.3

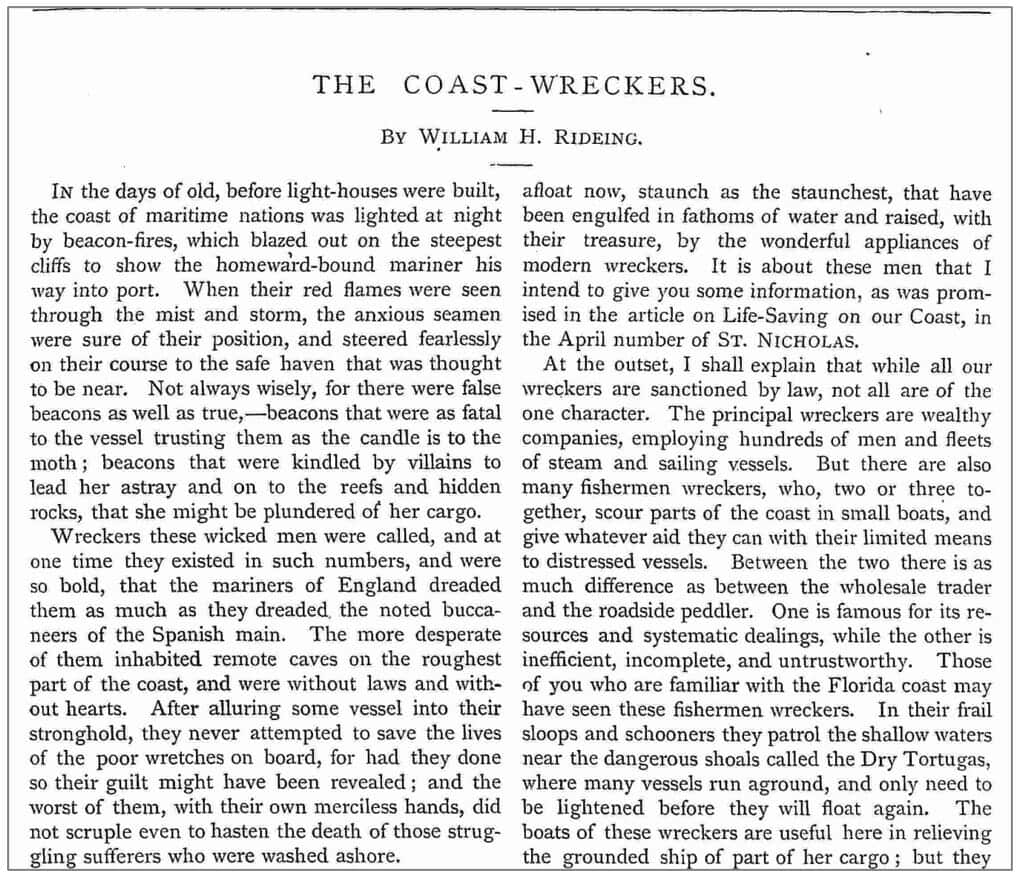

RIDEING, WILLIAM H. “THE COAST-WRECKERS.” St. Nicholas Scribner’s Illustrated Magazine for Girls and Boys, vol. I, no. 8, 1 June 1874, pp. 481+. Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/DX1901890894/GDCS?u=univbri&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=7be194bc

However, this myth is exaggerated, and du Maurier’s representation of wreckers is not accurate. Another, contradictory article published by the Cornishman in 1931 admits that people had begun to ‘discredit stories relating to old-time wrecking.’ A Times article from 1983 admits that deliberate destroying of ships was ‘more a matter of legend than fact’ and that the deliberate luring of ships, using false lights, for example, ‘has no such evidence or even reliable hearsay to support it.’ This suggests that there was a realisation that du Maurier’s novel was not historically accurate.

Shifting Representations of Wreckers

This shift in the reporting on wreckers reflects a historiography that was beginning to discover that wreckers were not the murderous bandits that representations like that in Jamaica Inn suggested. We can also see from this that, not only were wreckers not murderous, they often helped the victims of shipwrecks. Carolyn Fry’s 2003 article from The Times documents her visit to North Devon to hear stories of wreckers on Hartland Quay. One of these is about a Belgian steamship who ran aground in the quay. Fry writes about how ‘villagers fired a line to the ship and saved the man.’ This demonstrates that people often tried to save sailors, contrasting with the image of Joss Merlyn who ‘smashed [a shipwreck victim’s] face in with a rock’ in order to keep his profits and stay out of trouble.

Marsden, Philip. “Around the ragged rocks.” culture. Sunday Times, 10 Apr. 2005, p. 39[S11]. The Sunday Times Historical Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/FP1803672109/GDCS?u=univbri&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=99268fdc

The Value of Gale’s Historical Newspapers

I used Gale’s archives in my Outlaws module to demonstrate this shift in reporting. Initially, newspapers and periodicals helped to create and further the myth of wreckers as murderous criminals, who lured ships to the coast and murdered survivors to capitulate on the bounty of ships. However, accurate historical research and the rise of social history contributed to a shift in reporting to convey the reality; that wreckers were opportunists who saw the bounty of wrecked ships as their rightful property, often trying to help sailors from the wreck. I relativise Daphne du Maurier’s novel Jamaica Inn in this narrative, as something that both added to and was influenced by the myth of wreckers as murderous criminals.

For more on exploring the reception of literature, and Gothic Literature specifically, take a look at:

- Exploring Receptions of Classical Literature with The Times Digital Archive and Gale Digital Scholar Lab

- Examining the Emergence of Gothic Literature in the Early Nineteenth Century

- How Might a Creative Writing Student Use Gale Primary Sources When Working With the Horror Genre?

- From Grimm to Gothic and Everything In Between: The Evolution of the Horror Genre

If you enjoyed reading about depictions of historical criminality, check out:

- The ‘Real’ Peaky Blinders of Small Heath, Birmingham

- Gangster’s Paradise: Exploring British Media Coverage of American Organised Crime

- Atmospheric but Not Accurate – Five Ways ‘Peaky Blinders’ Stretched the Truth

- The Whitechapel Murders: exploring Jack the Ripper’s victims in Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture

- Trials, Tribunals and Tribulation: Witch-Hunts Through the Ages

- Criminality in Whitechapel – Using Hand Written Text Recognition technology to help examine villainy and justice in Victorian London

- ‘A Genteel Murderess’ – Christiana Edmunds and the Chocolate Box Poisoning

- ‘The compartment was much bespattered with blood’: the Brighton Railway Murder

Blog post cover image citation: The Wreckers, 1791 by George Morland, Available on Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Morland_-_The_Wreckers_-_1993.41_-_Museum_of_Fine_Arts.jpg