By James Garbett, Gale Ambassador at the University of Exeter

“Here was the perfect setting for a crime of the blackest sort” states a captivating document about Jack the Ripper that can be found within Gale’s Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture, 1790-1920 archive; “a city with a network of winding streets; a city of tumble-down, rickety houses and filthy courts and gateways.” “Here took place,” the source continues, “over a stretch of 15 months, one of the most horrible series of murders the civilised world has ever seen”. Found in the ‘TS Wood Detective Agency Records’ collection, this document paints a terrifying and chilling image of the Whitechapel area of London in the late nineteenth century. It speaks of the labyrinthine nature and depravity of the district, as well as the heinous crimes that were committed there.

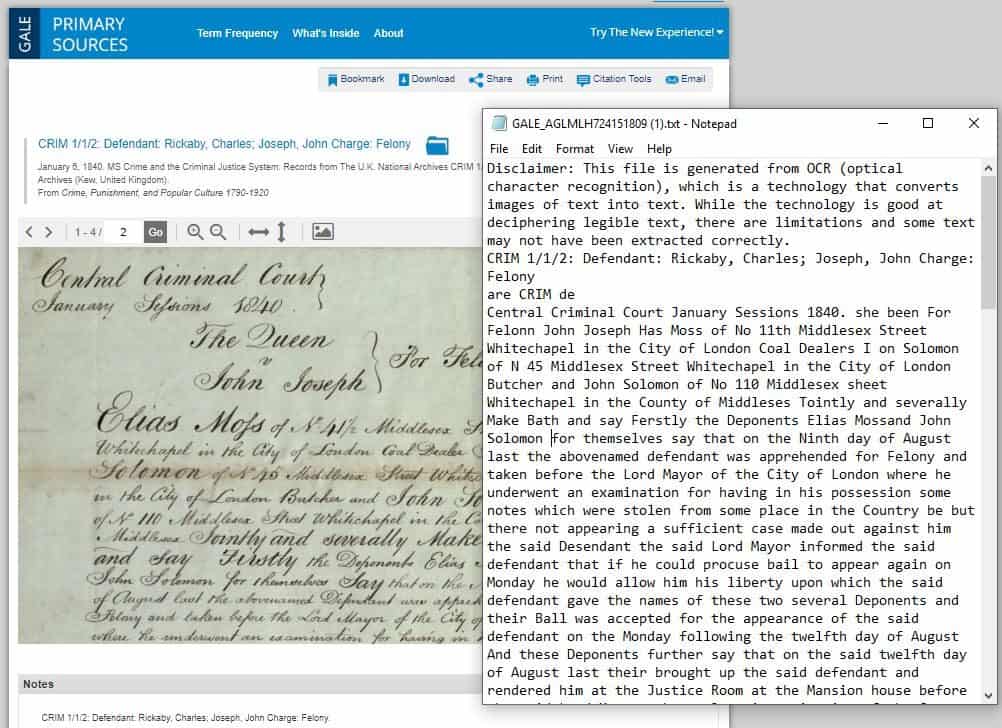

Whilst this document richly depicts the environment of the district, seven collections included in the Crime, Punishment and Popular Culture archive contain handwritten texts which can give us an understanding of the inhabitants of Whitechapel, both those operating within the law and against it. Simply searching ‘Whitechapel’ in these collections provides hundreds of results, including handwritten texts. Many are difficult to read due to their age and dated calligraphy. One of these documents found in the Crime and the Criminal Justice System collection from The UK National Archives is the court testimony of John Joseph, who was defended by John Solomon for a crime of ‘Felony’.

With the handwriting arduous to decipher, students such as I may find using the source in their research a daunting prospect. However, the new HTR technology available in Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture allows easy access to a transcription of the document – it takes just two clicks.

Clicking the ‘Download’ button as highlighted above, and then selecting the ‘OCR Text – Entire Document’ download option, users instantly obtain the transcript of the entire document in Notepad. This can be examined immediately alongside the original, manuscript document.

Thus, with the transcript, we can easily read that John Joseph “was apprehended for felony and taken before the Lord Mayor of the City of London where he underwent an examination for having in his possession some notes which were stolen from some place in the Country.” The source reveals further information to what occurred within the trial as ultimately “the Lord Mayor stated that he did not consider there was a sufficient case made out on which any Jury would convict the defendant and he therefore should discharge him upon his own recognizance to appear to answer any charge which might be made against him”. In making handwritten sources more comprehensible to those without palaeography skills, Gale’s Handwritten Text recognition technology can help students make greater and more effective use of these primary sources, and thus gain a greater understanding of the nuances of some of the crimes occurring in the late nineteenth century, unveiling aspects to the wrongdoings that would not previously have been accessible to them.

The potential to find exciting new documents here is unprecedented. Centuries old documents in Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture inform the reader of endless stories and criminal cases that are as extensive as they are intriguing and also give one a profound perspective of the methods of the Victorian justice system. One such source is a petition to Lord Viscount Melbourne, His Majesty’s principal Secretary of State. This petition is from the sister of a prisoner named George Jones, who stole Seven Shillings from William Ginn. Mary Cappas of Whitechapel asks in the letter to “Please Your Lordship to take this Petition into your humane and favourable consideration”.

HO 17/64/116: Petitions Lq-Ls; George Jones. 16 Oct. 1833. MS Crime and the Criminal Justice System: Records from The U.K. National Archives: HO 17 Records created or inherited by the Home Office, Ministry of Home Security, and related bodies, Home Office: Criminal Petitions, Series I HO 17/64/116. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture 1790-1920, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9cpqF7

Another helpful aspect of the new Handwritten Text Recognition technology is that, operating within the main search functionality, I can search printed and handwritten texts in Crime simultaneously, and pull results (and obtain transcripts) of both. As I continued my exploration of criminality in Whitechapel, I was also intrigued by the source below, also from the National Archives, which discusses the case of Henry Wainwright, who was “under sentence of death.”

Henry Wainwright was the owner of a brush making company, living at 215 Whitechapel Road who murdered his mistress Harriet Lane and buried her under the floor, aided and abetted by his brother, Thomas. Continuing my research in the Crime archive, I could find out more about the murderer. An article found in The Illustrated London Clipper, for example, confirms he was well known as a “lecturer and entertainer,” and gives us an insight into his personality, claiming his lectures are “delivered with great care and effect and the objects and aims of the writers are clearly and forcibly explained,” also stating that “the poetical and literary lectures of Mr H Wainwright have gained for him a well merited popularity.”

Yet this source reveals another side to Wainwright’s character, describing how, despite looking “pale and haggard,” during his trial, he “betrayed not the slightest emotion.” Another lengthy examination notes the statements made by a Mr Beasley, one of the police officers surrounding the case. Wainwright tried to buy-off the policemen who made the arrest, pleading “I’ll give you £100 – I’ll give £200 – and produce the money in twenty minutes, if you let me go”. Thus using the wealth of resources available in the archive allows me to obtain a deeper understanding of this individual from where my research began, with just his name in a record.

Thus, via both printed and handwritten texts (with the assistance of the new Handwritten Text Recognition technology) I have been able to explore some of the individuals that inhabited the winding streets of Whitechapel, revealing some of the intricacies involved and context behind crimes that blighted the area in the late nineteenth century.