|By Clem Delany, Acquisitions Editor, Gale Primary Sources|

Last week, I was lucky enough to go to India for the first time. I visited Mangalore in the state of Karnataka, as well as Kerala with its famous backwaters and cool green tea plantations in old hill stations. The British planted pine forests there and hid from the sun; in Mangalore old warehouses built along the river by the Portuguese for tile manufacture were visible from the high rise buildings around them. And everywhere – at busy roundabouts, by old government buildings and in front of smart new colleges – were statues and busts of solemn figures who I could not identify. The names Gandhi, Nehru and Modi are essentially the limit of my knowledge of modern India.

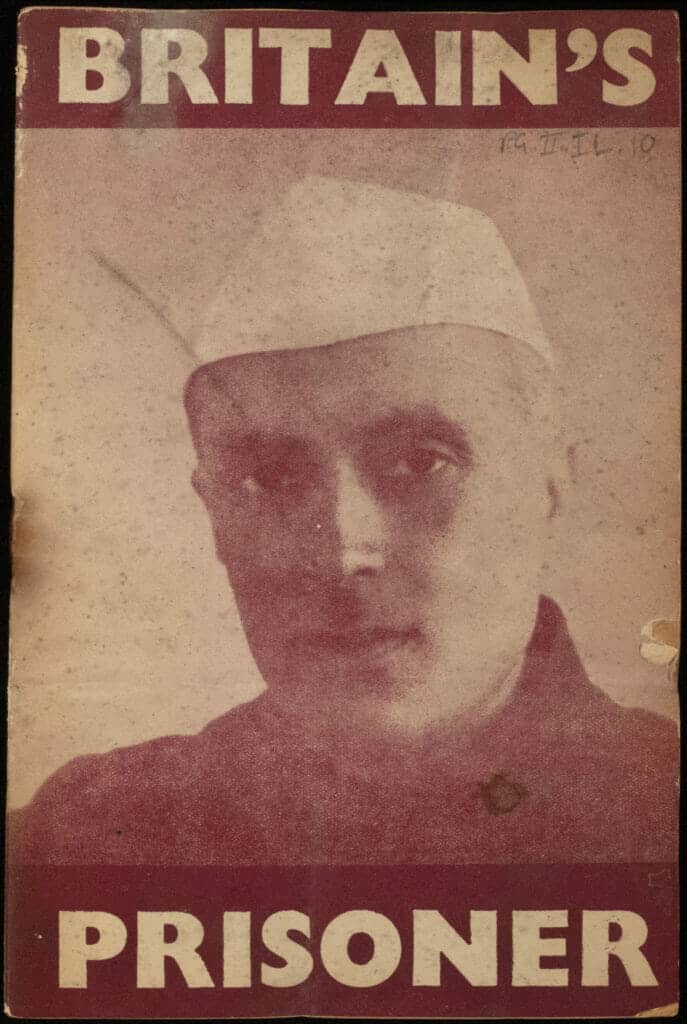

I am not alone in this; most British students (and those elsewhere in the Western world) are lucky if they are taught about Gandhi and the British Raj at school. Cotton and tea; salt and peaceful protest; independence and partition. These are the tent pegs of Indian and South Asian history as we are taught it.

What is the Legacy of Imperialism and Decolonization?

It is unnecessary for me to say that there is a whole lot more to learn! Indeed, in the last hundred years, India has changed so fast that my hosts in Mangalore – born and educated there but based in the UK for over thirty years – could point to few landmarks from their childhoods in the city centre. And it is the same story for many other countries whose histories were so intimately linked to Britain’s or other European Empires, but about which we learn so little.

Why was Ghana the first African country to gain independence from colonial rule? How do people discuss and frame environmental problems in the Caribbean? Who are the national heroes of resistance, and how do politicians approach international relations with one-time colonisers? What are the everyday concerns of the people, and what is the legacy of imperialism and decolonization?

Improving Access to Neglected Histories

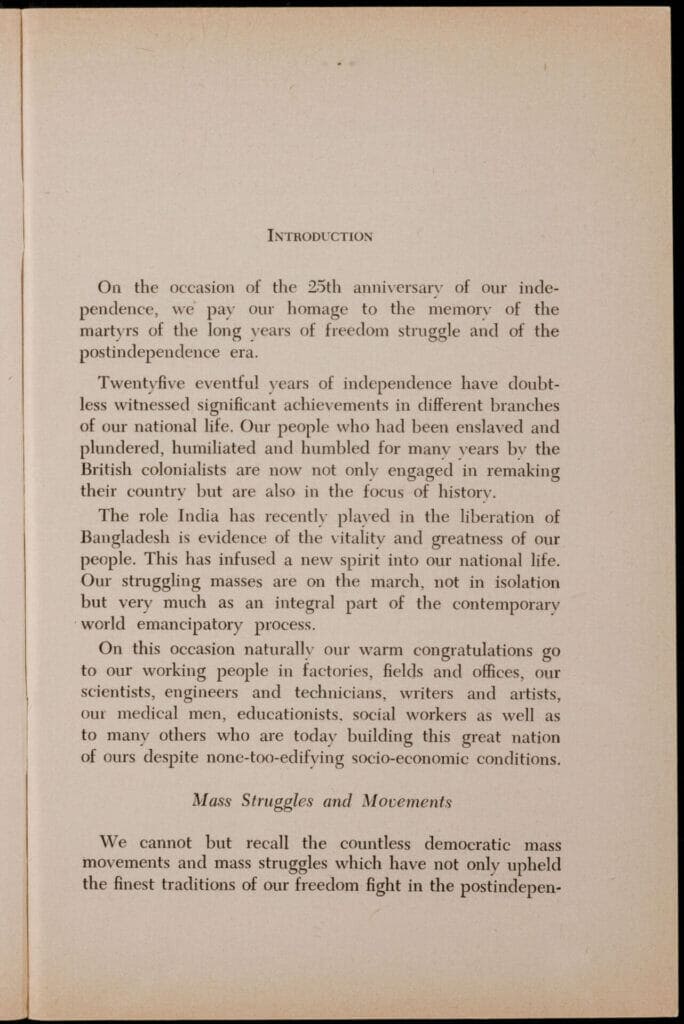

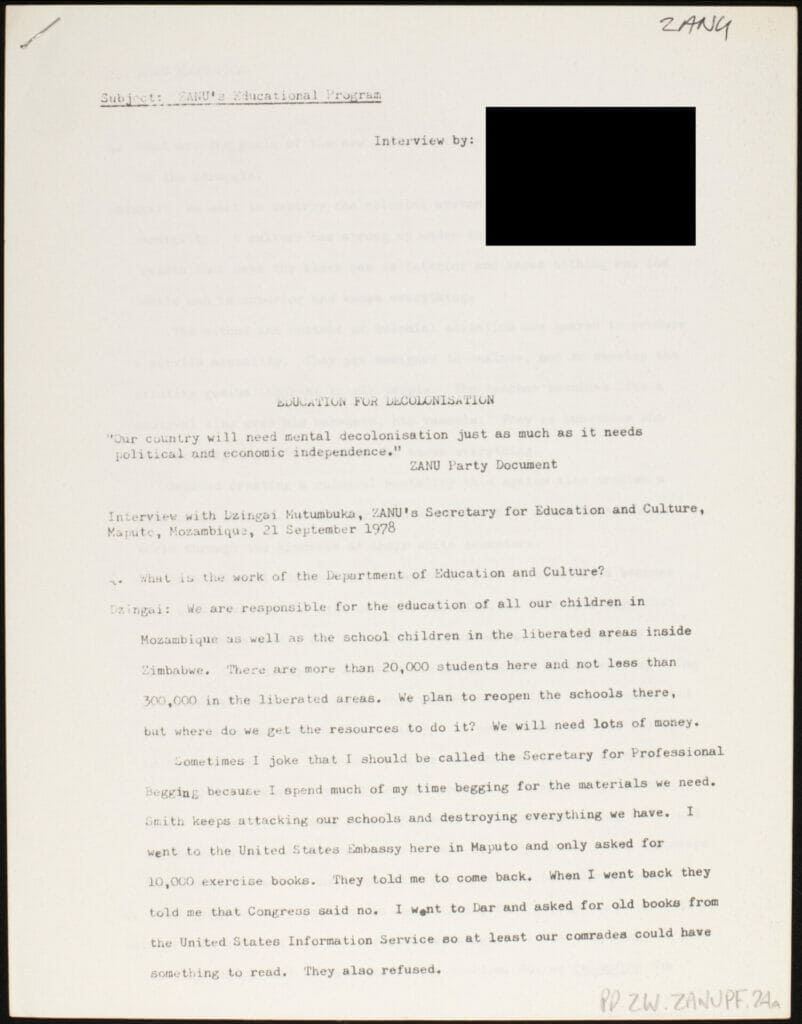

The Gale archive Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories brings together three archival collections of twentieth-century primary source materials in order to improve access to these neglected histories. The largest part of the material is the Political Pamphlets collection from the Institute of Commonwealth Studies (ICS) held at Senate House Library in London. Alongside this are a collection of African Trade Union material from Nuffield College at Oxford University, and the subject files from the Marjorie Nicholson papers of the Trade Unions Congress (TUC) Library, held at London Metropolitan University.

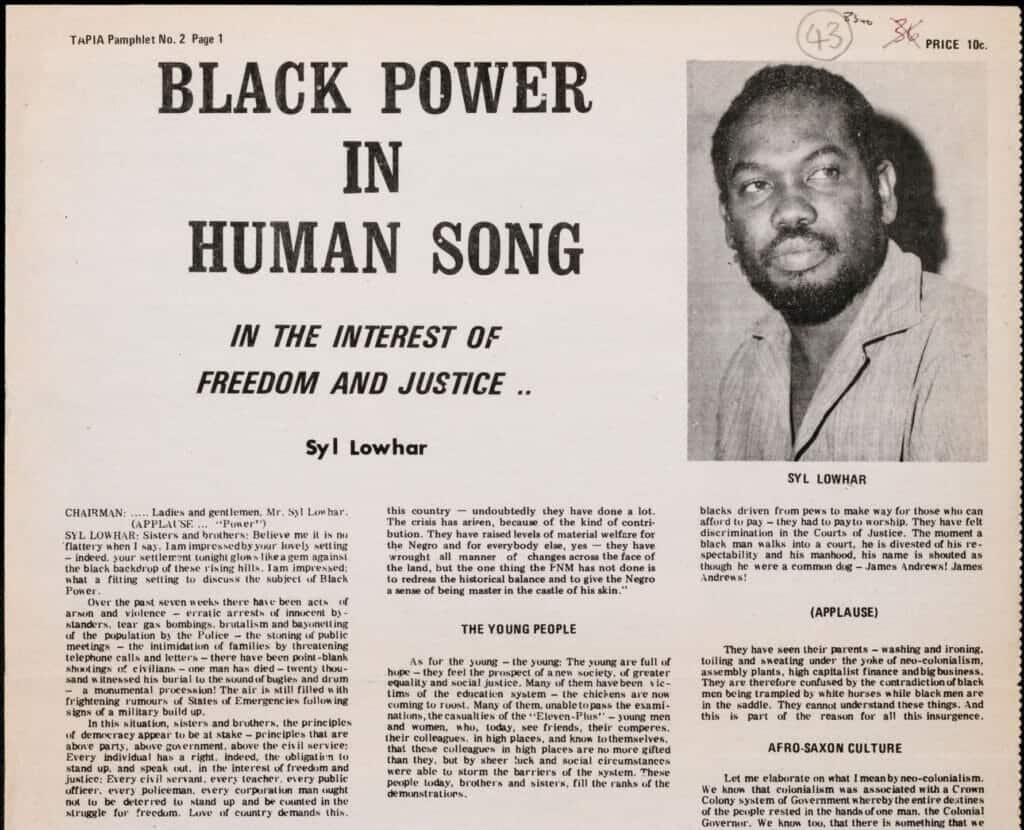

Primary source material is invaluable in finding diverse voices and in allowing students and educators to explore perspectives beyond their own experiences. Working with primary sources not only allows users to improve their research skills, to interpret and analyse sources critically and to expand their historical knowledge, it prompts curiosity and questioning in new directions, and about the material we cannot easily access.

It also leads to the crucial question: what happened next? And of course, what happens next?

What Will Researchers Find in This Digital Archive?

Over 70 countries are represented in this archive, some with thousands of documents and pieces of political ephemera from pressure groups, trade unions and political parties across a spectrum of ideologies – and some with only a handful of pieces.

The composition of these collections reflects the manner in which they were created; both the ICS collection and the collection of African Trade Union pamphlets at Oxford were put together initially in the 1960s and 1970s by contacting groups in different countries and asking for material. This was supplemented by material gathered by researchers on visits to the regions.

The TUC material differs from these collections, as it is the subject files of the papers of Marjorie Nicholson, who worked for the International Department of the TUC between 1955 and 1972. The papers she gathered relate to her interests in the international Trade Union movement, and include files on trade unionism in many different countries.

The Long Processes of Decolonization

It is worth noting that the ‘decolonization’ referred to here is not indicating the moment of independence in each country, or even the independence struggles that preceded it. Rather it relates to the long processes of decolonization, broadly begun in the early twentieth century and continuing to this day, by which countries and regions once under the power and influence of European empires approached the reshaping of power as the imperial presence withdrew, and the ways in which systems changed or adapted away from imposed imperial or colonial structures.

Different Forms of Decolonization

Processes of decolonization also take place in Commonwealth countries and former Dominions like Australia or Canada, where independence from Britain took an entirely different shape to that in, for example, Malaysia or Ghana. The ways in which these routes differed, and the reasons for that, are another facet of decolonization processes and global history that collections such as this can help researchers explore, as they offer the ability to compare regional material.

![Australian Independence Movement. [Leaflet Describing Aims of the Movement]. [1976]](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/image-6-484x1024.jpg)

Decolonizing the Curriculum

The collection also aims to address increasing calls to decolonize student curriculums by providing materials and narratives that include indigenous and diverse voices and go beyond the view of Western governments. One primary source collection like this is of course only a drop in the ocean, but it is a starting point for scholars who are looking for material by local and regional voices aimed at local and regional audiences.

With material created in South and Southeast Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, Australia and the Pacific, and the Americas, as well as items from international organisations, this archive caters to a wide scope of themes and subject areas including economics and development, trade and industry, society and culture, education, environment, race, gender and class.

Looking Beyond Independence

It is worth noting, finally, that the process of publishing this material included a long period of research and contacting copyright holders. Wherever there was sufficient information to identify potential copyright holders, they were contacted and asked for their permission to include the material in this digital archive. Some refused, and their material does not appear in the digital versions, although it is still held in physical form in the source libraries. The majority agreed, reflecting to an extent the original purpose of this material – to inform and educate, sometimes to convince or persuade, or rile up or call to action, but always to engage with wider audiences and the politics of nations, regions and people around the world in a fast-changing century.

In that, digitisation mirrors the original impulse; to better allow researchers and scholars to explore and understand places and peoples beyond the experience of colonialism and the direct moment of independence. Indian history does not pause at 1947, no more than Ghana’s history ceased in 1957 or Jamaica’s in 1962. The end of empire is only the beginning. What happens next?

If you enjoyed reading about Decolonization: Politics and Independence in former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories you may like:

- Decolonising the Curriculum with Archives Unbound

- Unearthing and Decolonising the Rasta Voice

- Discovering New Points of View about European and Colonised Women

- African Hairstyles – The “Dreaded” Colonial Legacy

- Indentured Indian Workers and Anti-Colonial Resistance in the British Empire

- Peyote Rights, Religious Freedom and Indigenous Persecution in the Women’s Missionary Advocate Papers

Blog post cover image citation: Montage of images created from primary sources shared in this blog post.