│By Grace Pashley, Gale Ambassador at the University of Birmingham│

Erotic literature and the representation of human sexuality has been around for thousands of years, whether that be the erotic lyric poems of Sappho of Lesbos or the highly commercialised Fifty Shades of Grey. Embracing one’s sexuality and authentically representing human experience has been and continues to be a contentious topic in the modern day. The Private Case from the British Library, one of the collections in Gale’s Sex and Sexuality, Sixteenth to Twentieth Century archive, brings to light erotic printed books which were previously deemed too deviant and morally corrupt to be available to the general public in the British Museum Library. Whilst The Private Case from the British Library is now a historical collection which is no longer updated, this historical archive provides readers with an insight into the realities of sexuality, desire and contemporary attitudes around sex at the time that these books were produced.

Despite the benefits of uncovering the perceived, or potentially true, realities of intimacy in a period when sexual desire was condemned and criminalised, we must remember that much of the erotic literature is written by men for men. The representation of women in erotic literature is often limited as women are objectified by the male gaze, and not able to voice their own thoughts about their sexual encounters. Whilst objectified, women are still represented as individuals who enjoy sexual encounters, but usually only in service of men, and have little to no agency in these sexual encounters. Yet, whilst it’s important to recognise the male gaze and its impact on how women and their sexual desire is portrayed, The Private Case from the British Library is able to provide researchers with an unabashedly revealing depiction of human sexuality.

Female Power in Sexual Encounters

The Loves of Venus, or the Young Wife’s Confession is a Victorian erotic novel published in 1881 which reminiscences on the sexual encounters of a husband and wife, and perversely the incestuous relations between a brother and sister. The text varies from poems to letters addressed to one another, and even includes very explicit drawings of their sexual encounters.

One poem is written from the perspective of a newlywed woman, Emma, as she recollects having sex on her wedding night. Despite her initial reservations and ‘prudish resistance’, Emma embraces her sexual desires. Emma’s initial hesitancy highlights the conflict between the societal shame surrounding sex at the time and the sexual duties Emma feels she has to perform as a wife.

The drawing below illustrates how sex was both an enjoyable experience and an educational one. The woman depicted in the drawing is learning about the anatomy of a penis and both individuals are learning about how to gratify the other in the erotica.

![The Loves of Venus, or the Young wife's confession, etc. [With plates.]. Privately Printed, 1881. Archives of Sexuality and Gender.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Gale-Review-3_Page_1-679x1024.jpg)

Sex is also portrayed as a sacred, heavenly act between husband and wife, as Emma is described as having ‘wafted to heaven’. Emma then embraces the pain and pleasure induced by sex and goes on to take charge of their sexual encounter:

‘I courted brisk action, and whispered, “push on.”

All attention, he promptly the summons obeyed’

In this way, Emma reverses the power dynamic by telling her husband how she wants to be pleasured and being unashamed of her desires.

![The Loves of Venus, or the Young wife's confession, etc. [With plates.]. Privately Printed, 1881. Archives of Sexuality and Gender](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/wafted-to-heaven-highlighted.jpg)

Limitations of Female Sexuality

Despite the progress which erotica makes by dealing with stigma around sexuality, the portrayal of women is often constraining and limiting. Even the sexual encounter above, in which Emma is portrayed to have some agency is clearly written with a male perspective in mind. Emma repeatedly uses language of conquest, and refers to herself as ‘his snug little dwelling’ – an object for pleasure and comfort, rather than an equal.

The dichotomy between husband and wife, and their sexual roles, is also seen through the explicit labels of ‘lion’ for her husband and ‘his prey’ for Emma. Although Emma is proud of her sexuality, it is only praised in the context of pleasuring her husband. Sex is regarded as an obligation for women rather than an option.

![The Loves of Venus, or the Young wife's confession, etc. [With plates.]. Privately Printed, 1881. Archives of Sexuality and Gender.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Gale-Review-2_Page_1-648x1024.jpg)

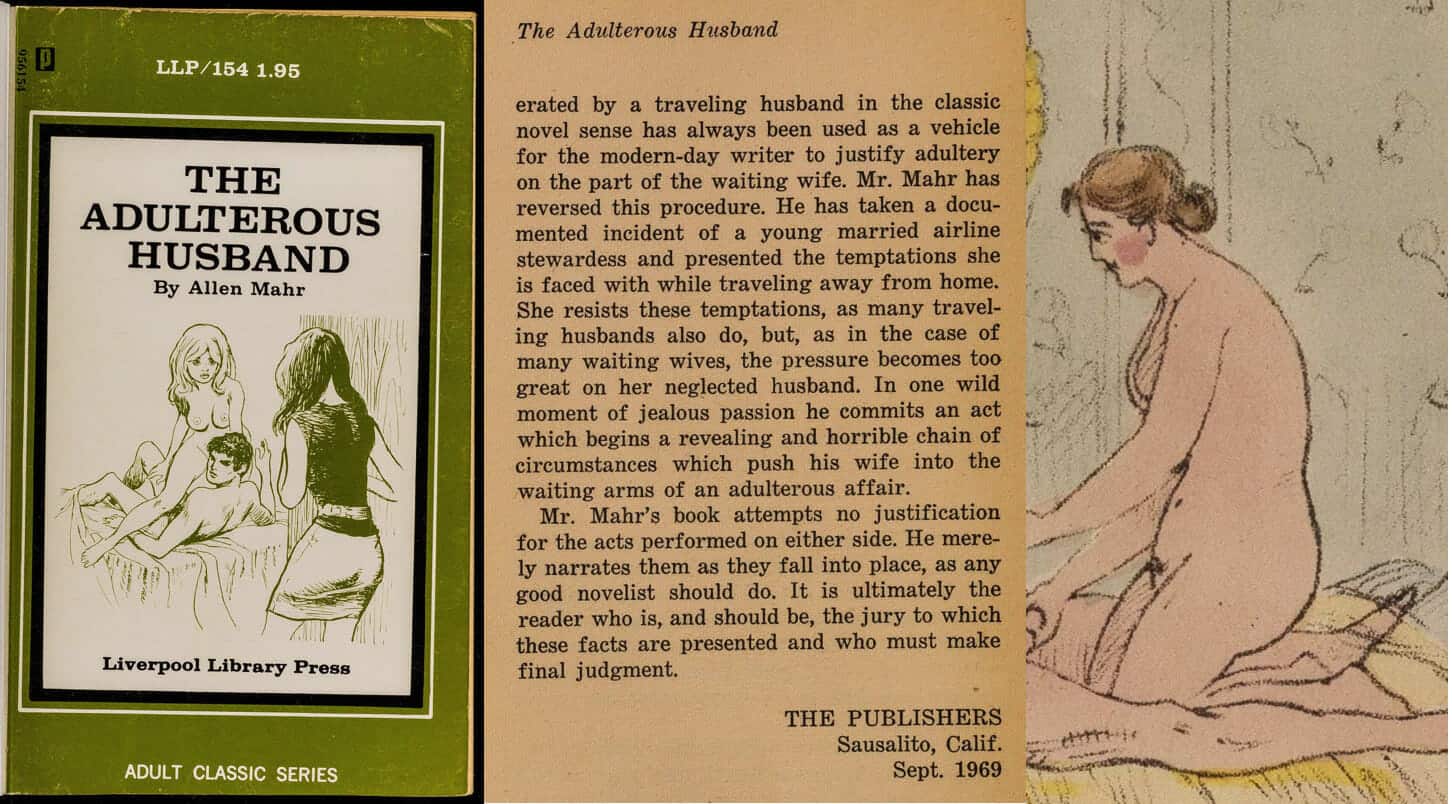

The Adulterous Husband by Allen Mahr (1969)

In The Adulterous Husband, a classic adult novel published in 1969, the reader follows the story of a married airline stewardess and her husband who both decide to cheat on one another and the wife eventually begins an affair.

I found the foreword of this erotic novel, where the publisher comments on the morality of the actions of the characters and the book as a whole, especially interesting. Here the publisher writes: ‘Mr Mahr’s book attempts no justification for the acts performed on either side. He merely narrates them as they fall into place, as any good novelist should do. It is ultimately the reader who is, and should be, the jury…who must make the final judgement.’ In this way, the publisher is emphatically insisting on the amoral status of the erotica (that the novel is labelling the actions of the characters as neither moral or immoral, instead leaving it up to the reader to decide).

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/PYGAGE046388994/AHSI?u=bham_uk&sid=bookmark-AHSI&xid=c9435e9b&pg=13

But I would argue differently. Despite the supposed amoral status of the erotica, the female protagonist is already cast in a negative light in the foreword, as her husband is deemed ‘neglected’ and her feelings are ignored. And when the erotica describes a sexual encounter between Larry, a pilot, and Bobbi, Mahr villanises Bobbi. The author frames Larry’s sexual assault of Bobbi as Bobbi’s fault, regardless of Bobbi’s explicit lack of consent.

Throughout the book, Bobbi, the air stewardess, is continually sexualised and objectified by all the men she encounters. Mahr also romanticises the violence and brutality of sexual encounters and normalises the blatant disrespect with which Bobbi is addressed. Her husband, for example, shouts at Bobbi:

‘Well, maybe if you weren’t such a gadabout glamour girl… such a spiffy fly-girl… ‘servicing’ all those passengers, all those johns who only fly the very best…’

Thus Bobbi is shamed by her husband for pursuing a career which she loves and not adopting her role as housewife and homemaker. She is condemned for failing to uphold the standards her husband deems fit for a wife and woman.

Women are continually viewed as sexual objects whose sole purpose is providing sexual gratification for men.

An Overlooked Branch of Literature

The Private Case from the British Library offers a myriad of different sexual encounters in the form of erotic literature which offer readers a perspective on contemporary attitudes towards sex at certain points in history. It is important to note the limitations, as erotica often catered to a male perspective and fails to capture the authentic experience of sexual encounters from a women’s perspective. At the same time, erotic literature is an area which is often overlooked and stigmatised, even though it contains valuable insights into attitudes and, albeit fictionalised, sexual encounters of people at that time. So to truly appreciate the immense value of erotic literature, I would recommend exploring this collection yourself!

Search for ‘Archives of Sexuality and Gender’ in your library catalogue, then, if the resource is available at your university, you will be able to select ‘Sex and Sexuality, Sixteenth to Twentieth Century’ which contains The Private Case from the British Library:

If you enjoyed reading about how females protagonists are presented in erotic literature, try these other insightful articles:

- Early Modern Medicine: Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health

- Exploring news coverage and media discussion of sexual violence

- L’Enfer de la Bibliothèque nationale de France – A Student’s Perspective

- Exploring Early Modern Erotica and Social History in L’Enfer de la Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Exploring Twentieth-Century Art and Social History in Erotica from L’Enfer de la Bibliothèque nationale de France

If you want to learn more about the archival content in Sex and Sexuality, Sixteenth to Twentieth Century, check out:

Blog post cover image citation: A montage of images found throughout this blog post.