│By Dr Lucy Dow, Gale Content Researcher│

On May 30, 1845 the first ship carrying indentured Indian immigrants arrived on the Caribbean island of Trinidad from Kolkata (Calcutta). This day is now commemorated in Trinidad as “Indian Arrival Day”. In this article I will use Gale Primary Sources to explore the history of Indian indenture and the South Asian community in the Caribbean, and elsewhere. In doing so, I will highlight how Gale Primary Sources can be used to better understand the role of the British Empire in moving people around the globe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and the inter-connectedness of anti-colonial movements across the British Empire.

The abolition of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies

Following significant uprisings by enslaved people in the Caribbean, and anti-slavery activities in Britain, slavery was abolished in Britain’s Caribbean colonies in 1833. The abolition of slavery was followed by a period of continued forced labour referred to as “apprenticeship”. The apprenticeship system ended on 1st August 1838 and enslaved people, predominantly of African descent, achieved full emancipation.

After emancipation many formerly enslaved people did not want to continue working on the sites of their former enslavement, leading to a shortage of agricultural workers in many of the Caribbean sugar economies. To provide workers for their plantations, former slave-owners and the British government agreed to set up a system of indenture, predominantly from British India.

Indentured labour

Indenture is a form of labour where the worker agrees to a period of unsalaried work in exchange for eventual payment or debt repayment. In the case of the indentured South Asian workers in the Caribbean (often referred to as “Coolies”), they were recruited by local recruiters in rural areas around major Indian ports.

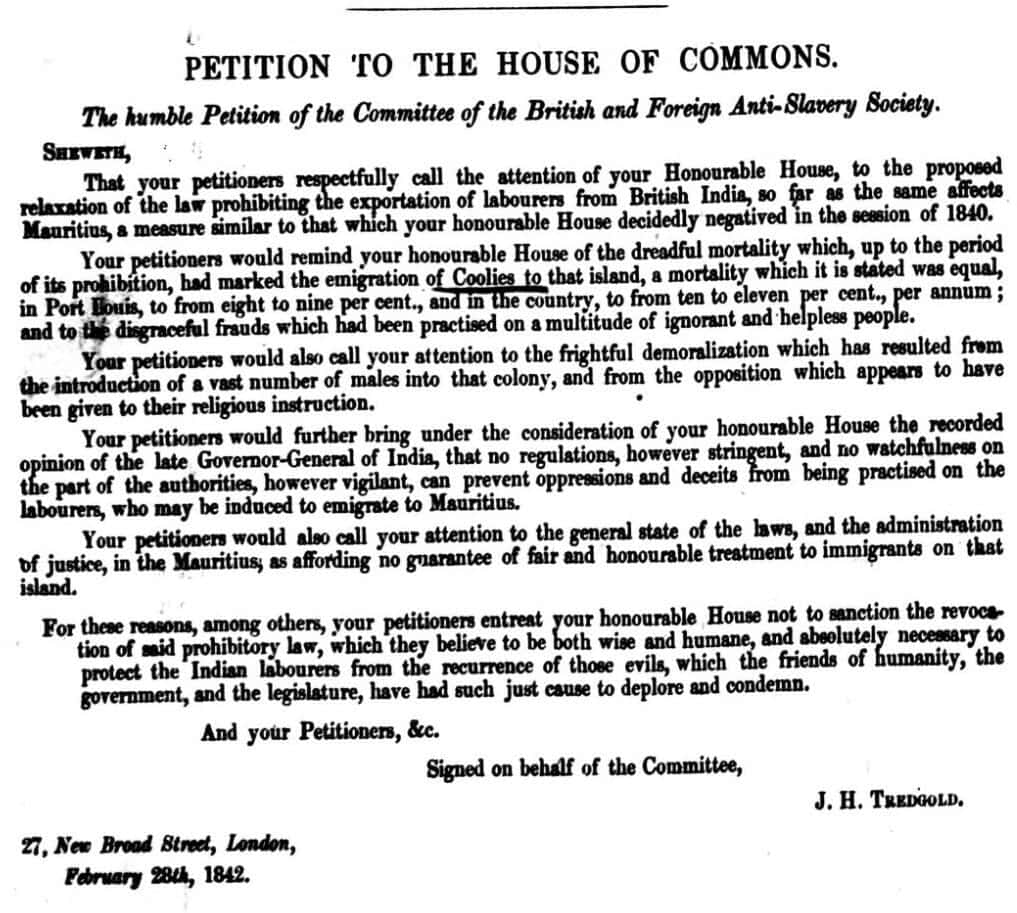

The movement of Indian workers to former slave economies had already started in Mauritius in the mid-1830s. As this petition by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1842, found in Gale’s Slavery and Anti-Slavery: A Transnational Archive, notes, “the exportation of labourers from British India” to Mauritius had already been noted for its “dreadful mortality” and “frightful demoralisation”.

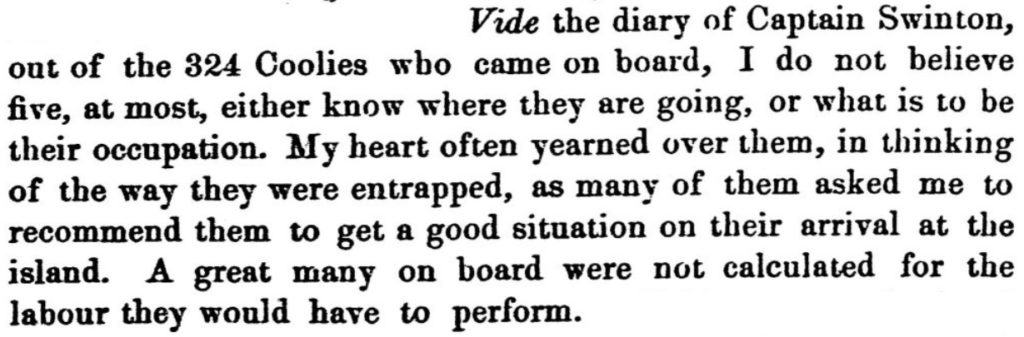

In spite of this, the British government agreed to allow the movement of indentured workers from British India to the Caribbean (and parts of Africa). Another source from Slavery and Anti-Slavery: A Transnational Archive, an 1859 account by a ship’s captain’s wife, highlights there was concern at the time as to the extent to which these indentured workers were made aware of what they were agreeing too:

Adapting to colonial life

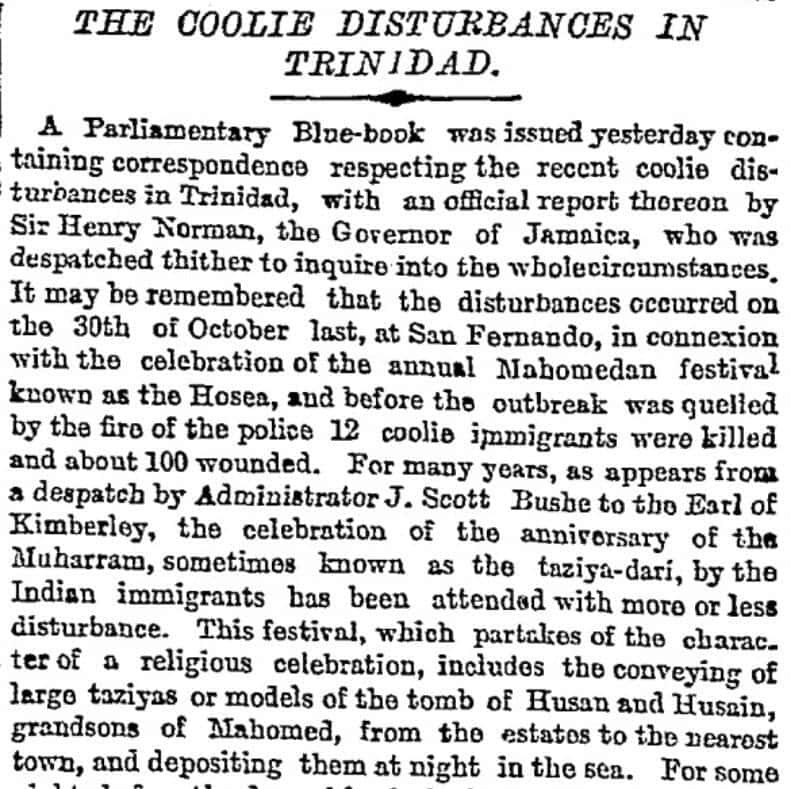

Despite these concerns the system of indenture continued until 1917. During this time many indentured South Asians chose to stay, or were sometimes coerced into staying, in the Caribbean after their period of indenture (which ranged from 5-10 years). As increasing numbers of South Asian people settled in Trinidad, they adapted their religious and cultural practices to their colonial life. In this 1885 article from The Times Digital Archive, the author estimates that the Indian population constituted approximately a third of the island’s overall population. The article is describing events around an Indo-Muslim festival that is held annually on the island, Hosea or Hosay:

The Hosay Massacre

The events this article describes would come to be known as The Hosay Massacre, when colonial troops fired on the Hosay procession after the crowd had refused to disperse before entering the city of San Fernando. As this extract details, twelve indentured workers were killed and around a hundred were wounded.

The inter-connectedness of anti-colonial movements across the British Empire

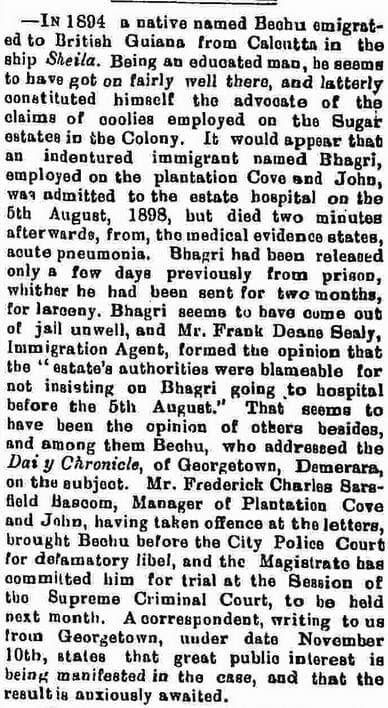

Events such as The Hosay Massacre fuelled wider concern amongst Indian political figures in British India as to the treatment of indentured South Asian workers in the Caribbean (and elsewhere). In 1898, an indentured Indian man known as Bechu was tried for libel after writing to the Daily Chronicle of Georgetown (the capital of British Guiana) blaming the managers of a plantation for the death of another indentured worker, Bhagri. The details of the case were reported in The Friend of India, a newspaper published in Calcutta (Kolkata) and can be found in Gale’s Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals archive:

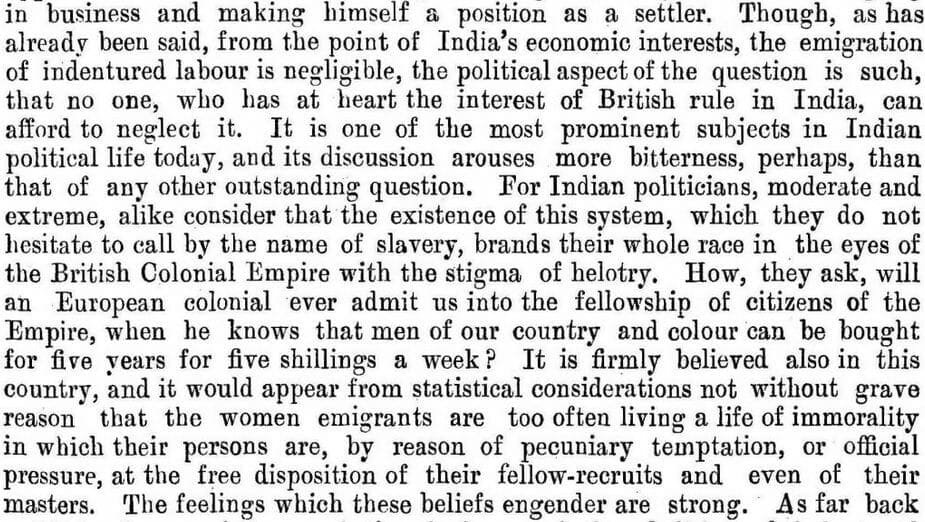

Increasingly, Indian nationalists saw indenture as a humanitarian crisis which not only affected the individual lives of the indentured workers but also undermined the position of India and Indians within the British Empire more generally. The imperial government in India tried to quell these concerns by conducting an investigation into Indian indenture, the McNeill-Lal report. However, this report did little to assuage the concerns of indenture’s critics, as was noted by the then viceroy, Charles Hardinge, 1st Baron Hardinge of Penshurst, in this confidential memorandum from October 1915 held in Gale’s Archives Unbound collection The Papers of Sir Austen Chamberlain:

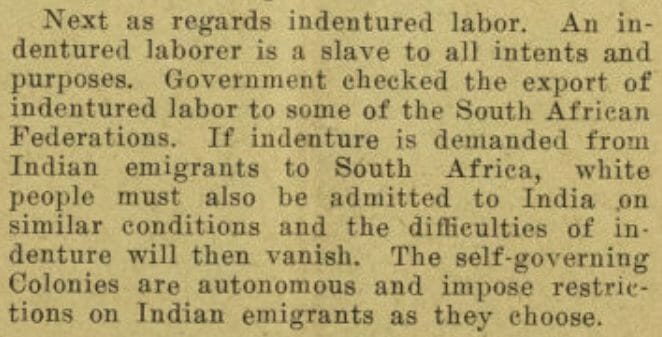

The relationship between indenture and the wider perception of Indians in the British Empire was of concern to Indians living in other parts of the Empire as well. This 1915 document from Gale’s China and the Modern World archive, India’s Appeal to Canada, or An Account of Hindu Immigration to the Dominion by “A Hindu-Canadian” quotes at length from a resolution at the 1914 Indian National Congress which highlighted the racialised inequality between white and Indian subjects of the British Empire. Indenture, in this case in South Africa, is given as an example of this inequality:

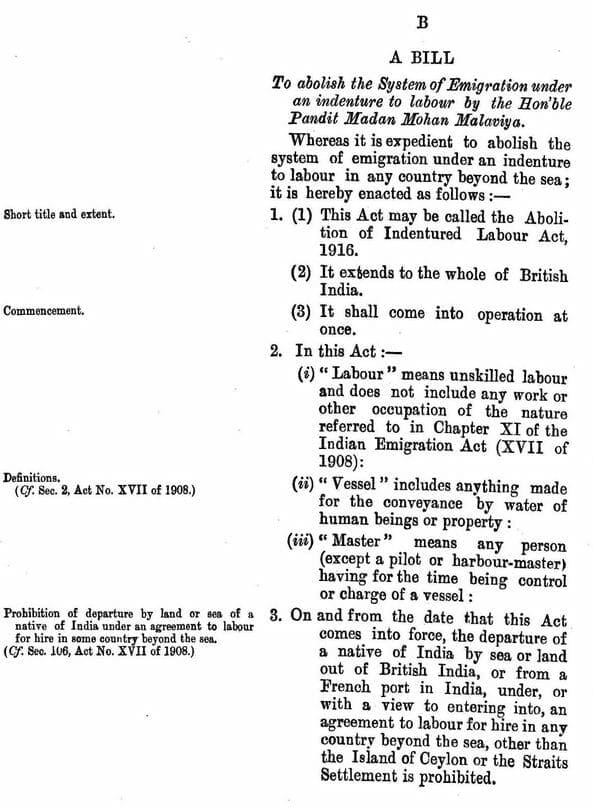

A particularly prominent critic of the indenture system was the Indian independence politician, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya. The Archives Unbound collection, The Papers of Sir Austen Chamberlain include a copy of the Imperial Legislative Council bill which was presented by Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya in 1916 and eventually led to the abolition of indenture:

As the Viceroy’s memorandum from 1915 above highlights, the British government hoped to placate Indian nationalists such as Malaviya with concessions such as the abolition of Indian indenture. However, anti-colonial movements in British India and elsewhere would continue to gain momentum, with India and Pakistan achieving independence in 1947.

A network of anti-colonial movements dedicated to resisting British imperialism

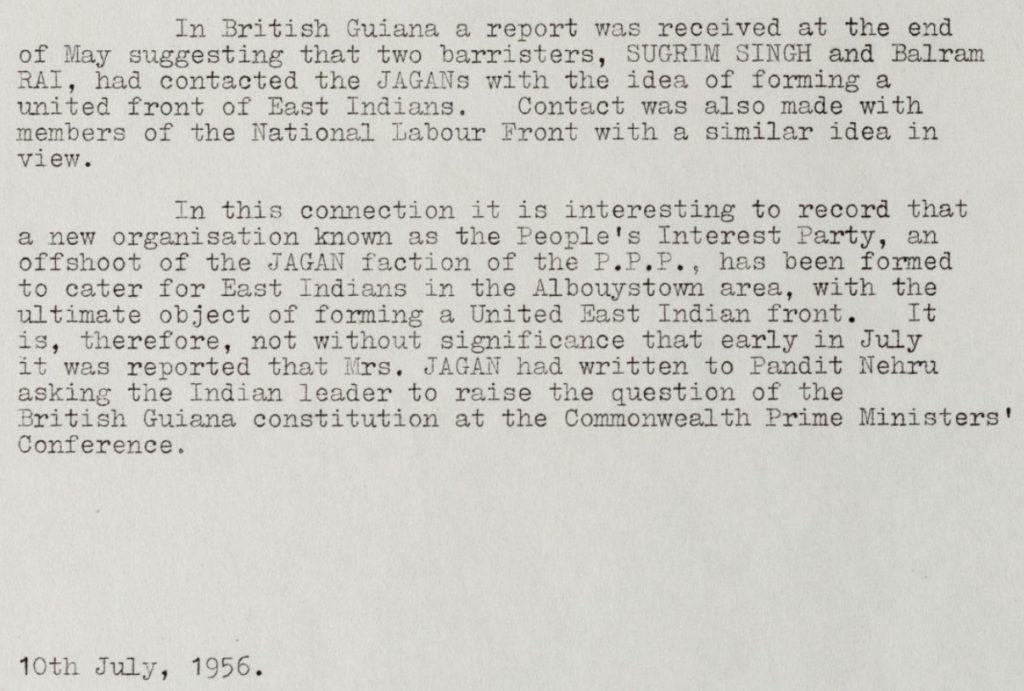

An independent India was seen by the British government as a potential support for other independence movements and thus a threat to the British Empire. This secret security review from Declassified Documents Online: Twentieth-Century British Intelligence includes details of communications between Guyanese-American political figure Janet Jagan, wife of People’s Progressive Party (P.P.P.) leader Cheddi Jagan, and Jawaharlal Nehru, a central figure in the Indian independence movement and independent India’s first Prime Minister:

Cheddi Jagan, who was a key figure in the Guyanese independence movement, was himself the child of indentured Indian workers. Thus we can see, through Gale Primary Sources, both how the British Empire moved people around the globe to serve its economic interests and how this in turn created a network of anti-colonial movements dedicated to resisting British imperialism.

If you enjoyed reading about anti-colonial resistance in the British Empire and the history of indentured workers in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, you might like to read:

- A Triumph for Humanity: William Wilberforce and the Team that ‘Bowled Out Slavery’

- Francis Barber: Samuel Johnson’s Jamaican friend

- Decolonising the Curriculum with Archives Unbound

- Exploring perceptions of Liverpool’s International Slavery Museum using Gale Primary Sources

Or try exploring other pieces on The Gale Review linked to empire.

Blog post cover image citation: South Asian workers preparing rice in Jamaica, 1895. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BKODEX729882137/GDCS?u=gale&sid=GDCS&xid=e4e2ca4c&pg=10