│By Meg Ison, Gale Ambassador at the University of Portsmouth│

In my last blog post for The Gale Review, I used my newly found freedom as a PhD student to indulge my intellectual curiosities during the festive period with Gale Primary Sources, exploring the celebration of Christmas around the world. My taste of freedom was short-lived! Studying for a Doctorate of Philosophy comes with many more obligations than one’s own research; you’re also expected to give papers at conferences, attend talks by established scholars, organise postgraduate study days and join research groups. And a particularly important part of the role is teaching undergraduate seminars. I am certainly not complaining, though – I’ve found I really enjoy teaching!

What do I teach?

My broad field of interest is European history, culture, politics and society. This is a key area of study in the myriad of subjects that constitute the department of Sociology, Area Studies, History, Politics and Literature at the University of Portsmouth, within which I teach BA History seminars. An important theme taught is the intersections of gender, race and class in different social, historical and political contexts. This area of research is timely since many Higher Education institutions have pledged to “decolonise the curriculum” and increase equality and diversity.

In keeping with these current research trends, I am currently teaching a seminar series which includes study of Empire and imperial culture in Britain to a group of first-year History undergraduates. A selection of secondary literature and primary sources are essential to the teaching of history seminars.

The popularity of gender-related themes in historiography about the British Empire

Since the 1990s, historians have studied the metropole and periphery together in terms of “co-construction” – the idea that Empire is not just an add-on to British national identity, but that the Empire built the British nation and vice versa. In these works, many historians find gender to have been commonly posited as a marker of difference and justification for imperial rule. Popular themes include:

- How the “native woman” was constructed by the (male) colonial gaze, and how this reinforced imperial rule.

- The impact of colonialism on gender relations and European gender norms.

- The extent to which imperial culture impregnated British society in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century .

For example, renowned scholar Gayatri Spivak speaks of the relationship between the colonised and coloniser in terms of “white men saving brown women from brown men,”1 and post-colonial studies as “white men saving brown women and men from epistemicide”2. Other academics have conducted oral history interviews with formerly colonised women who fought in nationalist wars for their independence. Works on Imperial Feminists are also popular, offering an alternative interpretation to Empire as patriarchal by shedding light on the work of British feminists in the colonies. However, Antoinette Burton has written about the Sutee in India as a “white woman’s burden,” and debates whether British Feminists were rescuers or facilitators of cultural imperialism.

These interesting types of secondary literature commonly feature on Reading Lists at Portsmouth because they write colonised women back into history and in doing so deconstruct the analytic categories of “gender,” “race” and “class”.

From these recent trends in historiography, an interesting discussion point came to my mind: To what extent did European women in history challenge or reinforce the “imperial gaze” constructed by European men? This is not a call to “re-colonise” the curriculum – far from it. Instead, it got me thinking about where I could find primary sources that might shed light on this topic, which I could then use in seminars to complement my History students’ secondary reading on Empire and imperial culture in Britain.

Where should I look for primary sources?

With a stroke of luck, the answer fell straight into my inbox when I was asked if I would like to trial a new Gale archive – the most recent module in the Women’s Studies Archive series, Voice and Vision.

The Women’s Studies Archive series launched in 2017 with Issues and Identities. After this, Rachel Holt, the Acquisition Editor for the series, began to research which additional primary sources would most benefit scholars of Women’s History and Gender Studies. Rachel analysed current trends in undergraduate and postgraduate courses and spoke to academics. She identified three recurring demands:

- A request for more literature penned by women, particularly periodicals.

- Better representation of women from around the world, especially minority groups.

- Coverage of topics beyond the fight for women’s suffrage, such as the abolition of slavery.

In response, Gale sourced documents concerning women from diverse ethnic backgrounds, including European, African American, Indian and Irish women, as well as religious minorities including Jewish, Muslim and Quaker. This became the Voice and Vision module, which allows researchers to understand a variety of perspectives on women’s experiences and their impact on society. This addition to Women’s Studies Archive is extremely topical because the intersections of gender, race and class are inherent. Thus university libraries might like to consider this collection if they’re seeking to decolonise their curriculum.

PART I: EXPLORING THE ARCHIVE

Key concepts and chronology

To guide my first steps into the archive, I made a list of key words relating to stereotypes about colonised women that were commonly appropriated by European men, such as: Islam, Muslim, oriental, veil, harem, Arab and Fatima. Predictably, these broad terms yielded thousands of results. I then used a filter available in the archive interface to narrow my results down to periodicals. I decided to focus on this content type because Women’s Studies Archive contains a whole collection called European Women’s Periodicals. Still faced with hundreds of sources, I then thought about the kinds of questions I could ask of the database. I decided to identify particular dates when certain key words appeared more frequently, to construct a chronology that shows how discourse evolved over time. Women’s Studies Archive allowed me to do this via the Term Frequency function.

To conquer or to imitate?

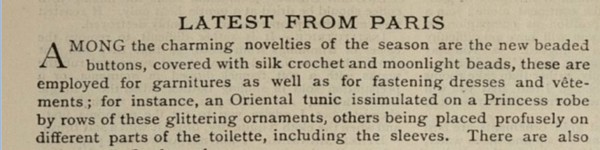

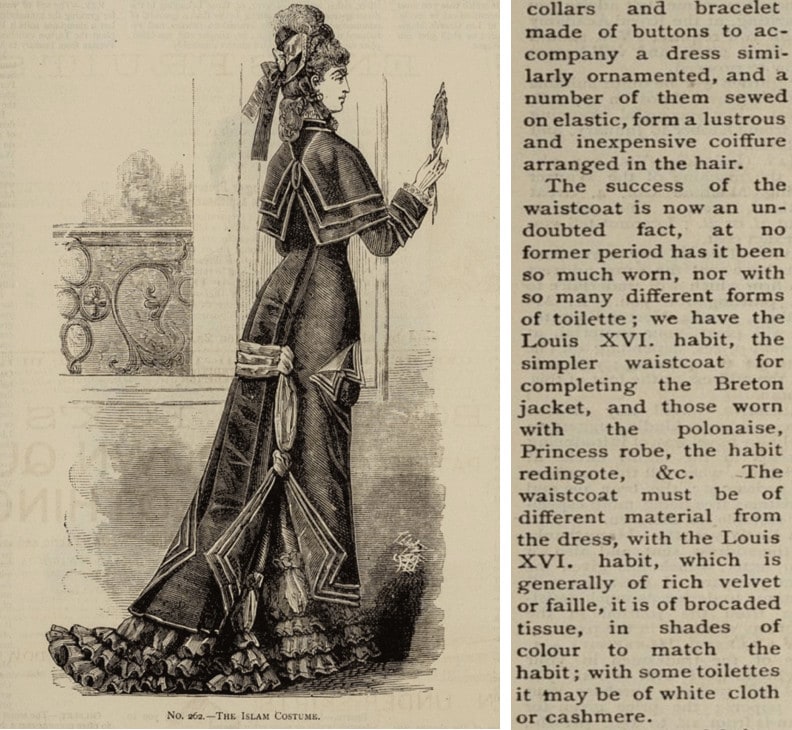

Interestingly, whilst there is consensus in the secondary literature that the “colonial gaze” of European men was fixed on the veil worn by Muslim women as a symbol of their ‘otherness’ – meaning the irreconcilability of European Christian culture with North African Islamic culture – I found lots of sources from the 1870s–1890s that suggest upper-class women were more concerned with imitating the beautiful styles of Islamic fashion. In other words, whilst European men viewed colonised women as mysteriously inaccessible symbols to conquer, European women adopted their style and made it accessible to other rich women in the metropole. Here are some examples:

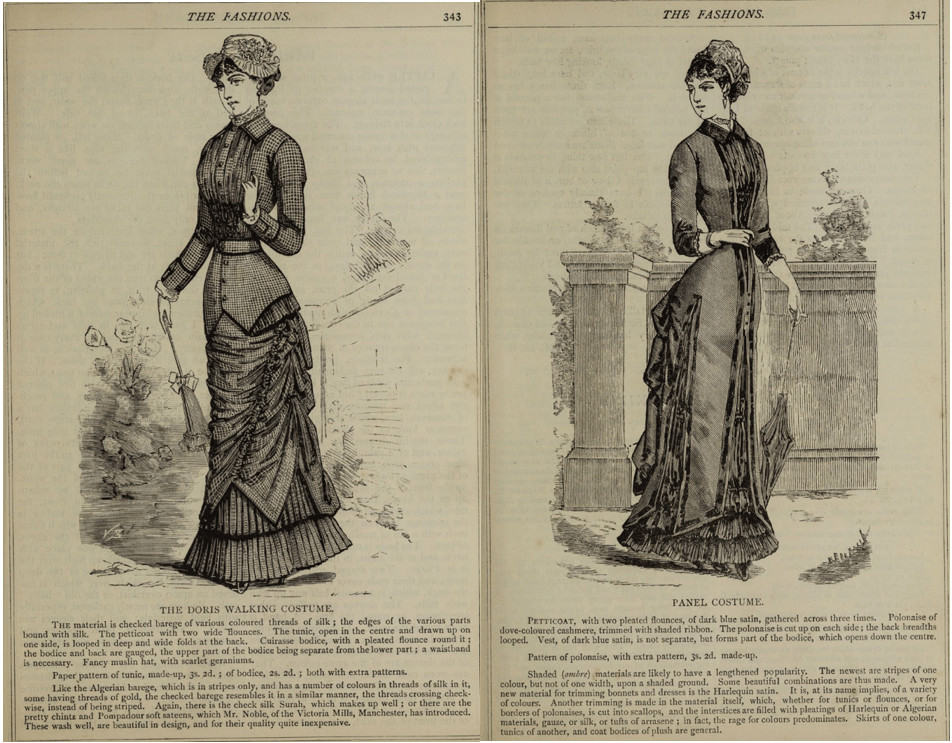

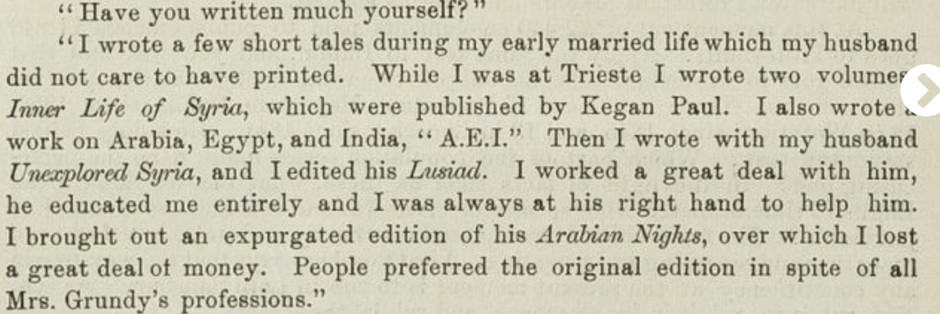

Twenty years later, many periodicals printed articles that suggest upper-class women in Britain were still inspired by colonial fashion, especially home interiors. An interesting example is the interview below with Lady Burton, an English writer, whose husband, Sir Richard Francis Burton, was an explorer and adventurer:

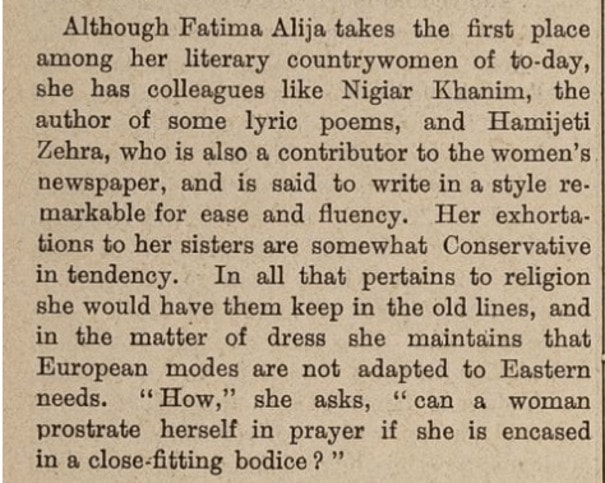

On the other hand, The Woman’s Signal reported that women living in overseas territories were drawn to Islamic clothing for more practical reasons:

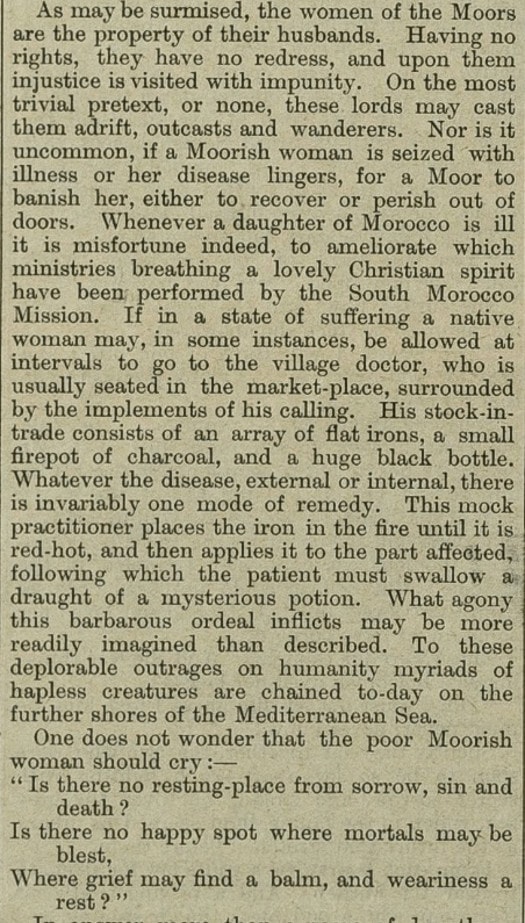

At the same time, some men managed to get articles published in European women’s periodicals which warned their readership that behind the façade of oriental beauty were dangerously uncivilised Muslim men from whom Muslim women need saving. This is evidence of the classic justification of colonial rule along gendered and racialised (/religious) lines that the secondary literature frequently discusses. The article below from 1896 by James Johnston epitomises this trend well:

Some European women challenged prevailing views

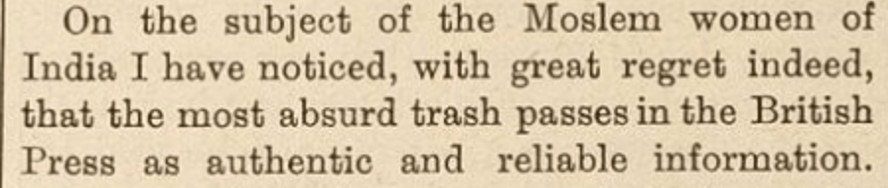

However, I found other articles penned in the 1890s by British feminists which suggest some European women challenged these representations of colonised women. For example, the primary source below demonstrates how some women directly called into question the reliability of the prevailing “facts” about women’s rights in Muslim cultures:

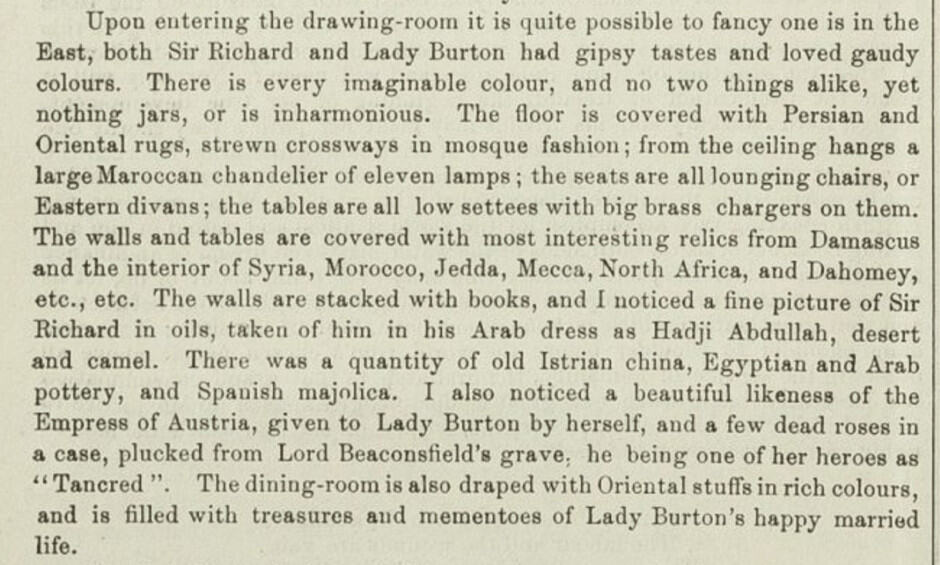

Colonial romance stories reinforced western stereotypes

However, there was also a proliferation of romance stories published at this time which reinforce the western stereotypes of “manly men” going off to explore and conquer Africa and “romantic women” viewing them as brave heroes. These sources could suggest that, whilst some women challenged the male “imperial gaze,” female vision was still framed by conservative European gender roles that remained entrenched in the metropole. Here are some examples of such stories:

![A close up of a newspaper

Description automatically generated

"Chapter V." Lady's Own Novelette, vol. 4, no. 141, [July 29, 1891], p. 22+. Women's Studies Archive,](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Meg-WSA-post-Novel-1.jpg)

![A close up of a newspaper

Description automatically generated

"Chapter V." Lady's Own Novelette, vol. 4, no. 141, [July 29, 1891], p. 22+. Women's Studies Archive](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Meg-WSA-post-Novel-2.jpg)

![A close up of text on a white background

Description automatically generated

"Chapter III." Lady's Own Novelette, vol. 1, no. 21, [April 10, 1889], p. 20+. Women's Studies Archive](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Meg-WSA-post-Novel-3.jpg)

![A close up of text on a white background

Description automatically generated

"Chapter IV." Lady's Own Novelette, vol. 3, no. 61, [January 15, 1890], p. 22+. Women's Studies Archive,](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Meg-WSA-post-Novel-4.jpg)

![A close up of a newspaper

Description automatically generated

"Chapter VIII." Lady's Own Novelette, no. 398, [July 1, 1896], p. 29+. Women's Studies Archive,](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Meg-WSA-post-Novel-5.jpg)

European women who fought alongside men

However, it should not be taken for granted that all European women behaved in the “conventional” way that their sex dictated. For example, also during the 1890s, the Feminist paper The Woman’s Signal published features on brave European women who had fought alongside European men in ferocious wars of colonial conquest:

It also emerges in periodicals published in the 1890s that some European women did not share their male counterparts’ “obsession” with the impenetrable realm of Islamic culture. This may be because (as the sources suggest) European women were better able to gain direct access to colonised women than European men based on their gender, and could thus provide more informed knowledge about the Muslim domestic sphere.

I found some great sources on two female ethnographers, Mrs French Sheldon and Madame Maria Martin, who wrote up their field notes into popular books about the “realities” of colonised women’s lives in the settler colonies. Martin wrote Arab Women in Algeria, whilst Sheldon promoted her research on British Kenya in a series of lectures including a talk at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

![Left: "Interview." Woman's Herald, vol. 3, no. 122, 21 Feb. 1891, p. [273]+. Women's Studies Archive,

Right: "Interview." Woman's Herald, vol. 4, no. 132, 9 May 1891, p. [449]+. Women's Studies Archive,](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Meg-WSA-post-Shedlon-and-Martin-combined.jpg)

Right: “Interview.” Woman’s Herald, vol. 4, no. 132, 9 May 1891, p. [449]+. Women’s Studies Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/TWLRAZ876882355/WMNS?u=womensstudies&sid=WMNS&xid=bf9762ed

Intersections between suffrage and colonialism

Following my examination of sources from the nineteenth century, I used the Date filter in Women’s Studies Archive to narrow my list down further to periodicals published after 1900. I started to notice that more periodicals were penned by Imperial feminists in the years before World War I, and inexplicit references to “race” and “purity” as a marker of social status were drawn upon in many of the suffragette writings about nationality and marriage rights for European women.

Right: De Alberti, L. “Imperial Conference of Women.” The Catholic Suffragist / Organ of the Catholic Women’s Suffrage Society, vol. 4, no. 7, 15 July 1918, p. 54+. Women’s Studies Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/OGWMRS646538664/WMNS?u=womensstudies&sid=WMNS&xid=1b216ec2

Explicit references to race also spiked in sources from the immediate post-First World War period when colonised men and women were quickly suppressed with the reassertion of colonial rule in Africa after the Allied defeat of Germany in Europe. Given this historical context, the reflections of some European women published in periodicals could be seen as being ahead of their time on issues of racial equality:

Influential women in the colonies

The sources showed me that from the interwar period onwards, British Feminists started to take a greater interest in suffrage activity in the colonies. For example:

And when the Wars of Decolonisation broke out following World War II, European women’s periodicals started reporting on the actions of influential European women based in Africa:

I found sources written by Mexican women resisting the cultural imperialism of the United States in the 1970s who looked back to their sisters in the Algerian War of Decolonisation as a source of transnational inspiration:

![A close up of a newspaper

Description automatically generated

External, Dorinda Moreno. La Mujer-En Pie De Lucha. 1973. 1973. MS The National Network of Hispanic Women Archives: Series II: Publications Box 81, Folder [U1]. University of California, Santa Barbara. Women's Studies Archive,](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Meg-WSA-post-What-is-this-tradition2.jpg)

Searching key concepts then filtering the results to construct an ad-hoc chronology has shown me that European women more often challenged rather than reinforced the “imperial gaze” constructed by European men.

PART II: HOW TO STRUCTURE A PRIMARY SOURCES SEMINAR

To encourage students to consider the extent to which the “imperial gaze” constructed by European men was challenged by European women, I would begin a seminar class by taking students through various methods to analyse primary sources. This could include how to read sources “along the grain” and “against the grain” to ask questions such as:

- What agency do colonised women have in these accounts?

- What are the authors’ different interpretations on women in Africa? Why do they agree or disagree? (Think about different times of publication, the social classes of authors and their different political motivations)

- What purpose do each of these articles/interviews serve? (apply the Who, What, When, Where and Why questions to each source)

- What are the differences in tone between the sources? How does thinking about the purpose of sources help us account for this?

- What do these differences tell us about European women’s views about colonised women? – their culture, legal status, political ambitions, etc.

- Whose perspectives are missing?

- What does this tell us about the importance of social class in shaping the opinion of European women?

- Did imperial suffragettes want to win colonised women the right to vote? How do we elicit this?

I would then encourage students to think about how they might put these sources together with the secondary texts on their Reading Lists, read in preparation for the seminar. The aim of combining primary source interpretation with historiography is to deepen students’ knowledge of a specific theme within the broad topic of imperial culture in Britain.

Final reflections on Women’s Studies Archive: Voice and Vision

In the words of Rachel Holt, Acquisitions Editor:

“As academia increasingly recognises the importance of Gender Studies as a discipline (as well as its links to and interdisciplinary significance in fields such as Sociology, Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Studies, Literature, Cultural Studies, Media and Journalism, Politics and more), the focus and study of Women’s History will continue to grow and become more varied. It is a very exciting time to be building digital archives in this area and Gale will continue to listen to researchers in order to meet their needs”.

As shown in this blog post, Gender Studies has strong links to Colonialism and Post-colonialism Studies. As such, to improve its breath and depth, I would suggest Voice and Vision could include more perspectives from outside the cultural imperialism of the anglophone academy, including more sources in French, German, Spanish, Arabic, etc. That being said, Women’s Studies Archive is a rich, revealing and relevant archive. It is easy to use and provides plenty of material for researchers to use in their teaching. As such, I would recommend this resource to scholars for research and teaching purposes.

Want to learn more about colonialism and Women’s History using primary source archives? Check out this post: Sporadic riots’ and ‘false reports’ – British Reporting of the 1929 Igbo Women’s War or Discover the History of British Hong Kong Through Handwritten Documents.

Blog post cover image citation: Image by Christina Morillo on pexels.com.