| by Masaki Morisawa, Senior Product Manager, Library Reference, Tokyo |

Last year, an American high school student’s twitter account flamed up when she posted prom pictures of herself wearing a cheongsam, or Chinese dress. Some Asian Americans accused her, who is not of Chinese descent, of cultural appropriation. “My culture is NOT your [expletive] prom dress,” wrote one particularly upset commenter. Others, including many Asians living in Asia, defended her actions and dismissed such criticism as irrelevant.

While “cultural appropriation” is a fairly recent term, similar debates have arisen in the past where the borrowing of “exotic” elements from foreign cultures have been criticised as offensive or disrespectful. One such example is Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera The Mikado, a work that is often hailed as the duo’s masterpiece, yet at times has stirred controversy due to its use of Japanese costume and settings. In this post I would like to take a look at the history of Mikado performances and the controversies surrounding them.

The Mikado

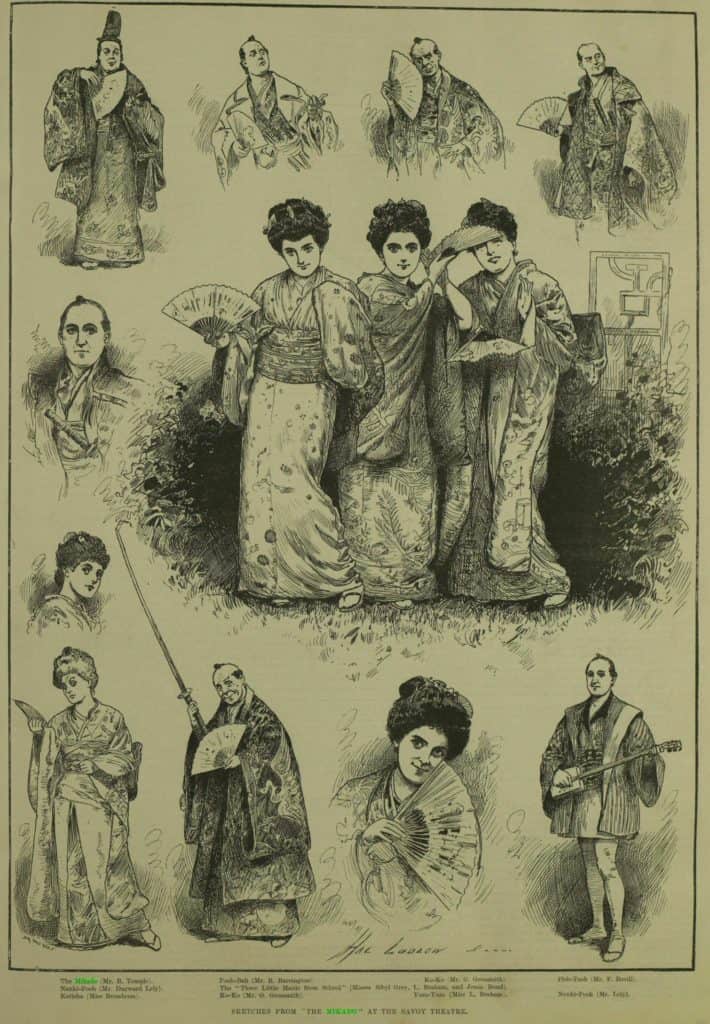

The Mikado is British librettist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900)’s ninth collaboration. It premiered at the Savoy Theatre in London on 14 March 1885. Set in the fictional Japanese town of Titipu, the opera revolves around the love triangle between Nanki-Poo, the crown prince in disguise as a wandering minstrel; Ko-Ko, a tailor turned Lord High Executioner of Titipu; and Yum-Yum, their mutual love interest who is also under the wardship of Ko-Ko. Other characters include the Mikado (Emperor) of Japan; Katisha, an elderly lady in love with Nanki-Poo; the noble lords of Titipu, Pooh-Bah and Pish-Tish; and the two sisters of Yum-Yum, Pitti-Sing and Peep-Bo.

The 1885 Production: Costumes, Set and Props

When I looked at contemporary photographs and illustrations of the 1885 production from Gale Primary Sources, what struck me the most was how accurate and authentic the Japanese costumes looked:

Apart from the obviously Caucasian faces, the kimonos, the hairstyles, the props—even the poses—are strangely familiar, resembling those Japanese actors and actresses appearing in our local period dramas on television. How did they get it so right visually?

The “Japanese Village” of Knightsbridge, London

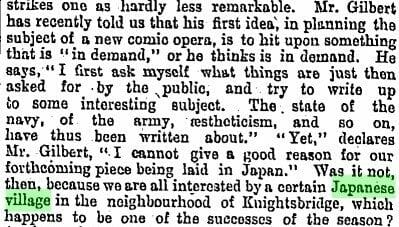

The Sunday Times review of the March 1885 premiere gives a clue. Dismissing Gilbert’s claim that he “cannot give a good reason for [their] forthcoming piece being laid in Japan”, the reviewer states slyly, “Was it not, then, because we are all interested by a certain Japanese village in the neighborhood of Knightsbridge, which happens to be one of the successes of the season?” (emphasis mine).

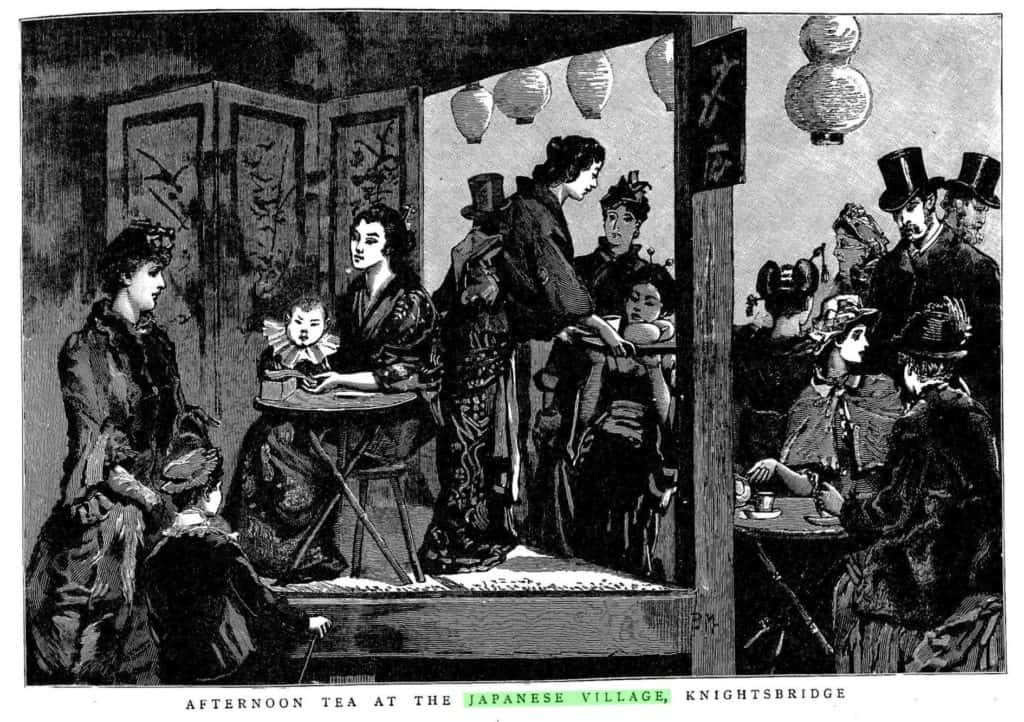

This “Japanese village” of Knightsbridge, London, opened in January 1885, was a sort of theme park where nearly 100 Japanese artisans and entertainers enacted various scenes from their everyday lives. It was the brainchild of one “Tannaker Buhicrosan”, a mysterious figure who often claimed himself to be Japanese (or half-Japanese), but whose name sounds equally outlandish to English and Japanese ears. Buhicrosan was actually the alias of a Dutchman, Frederik Blekman (1839–1894), who originally came to Japan as an interpreter, narrowly escaped punishment for embezzling Shogunate funds, assumed the Buhicrosan name to become an impresario of several Japanese juggling troupes (see my previous post), and then went on to mastermind the Japanese Village. It became a singular success, recording 250,000 visitors in the first four months.1

While it is debatable whether or not the initial inspiration for The Mikado came from the Japanese Village, with Buhicrosan’s help, Gilbert certainly took advantage of the presence of its actual Japanese artisans during the opera’s production:

Gilbert employed a male dancer and a geisha who knew only two words of English—”Sixpence, please,” the price of tea—from the [Japanese] village to instruct his cast in comportment, dance, makeup, and such details as the snapping of fans.

There is even this joke inserted in the opera referring to the village’s location in London.

KO. It’s quite easy. That is, it’s rather difficult. In point of fact, he’s gone abroad!

MIK. Gone abroad! His address.

KO. Knightsbridge!

A Biting Satire on Victorian England

Speaking of the opera’s libretto (the text of an opera), in contrast to the well-researched costumes and settings, I was struck by how little Japan is featured in the opera’s words. True, there are a few offhand references to Japan, and a couple of lines from Japanese songs for comic effect, but that’s about it. Instead, the majority of Gilbert’s satire seems to be pointed at his own people:

All prosy dull society sinners,

Who chatter and bleat and bore,

Are sent to hear sermons

From mystical Germans

Who preach from ten till four.

The amateur tenor, whose vocal villainies

All desire to shirk,

Shall, during off-hours,

Exhibit his powers

To Madame Tussaud’s waxwork.

Stripped of the elaborate costumes and visuals, the words alone sound like Gilbert is merely using Japan as a remote, exotic setting to camouflage his biting satire on Victorian England, much like Jonathan Swift used the fictional lands “Lilliput” and “Brobdingnag” in Gulliver’s Travels to cloak his.2 However, one crucial difference is that, while the odds of a Lilliputian or a Brobdingnagian chancing on Swift’s book is extremely low, the odds of a Japanese attending The Mikado is not.

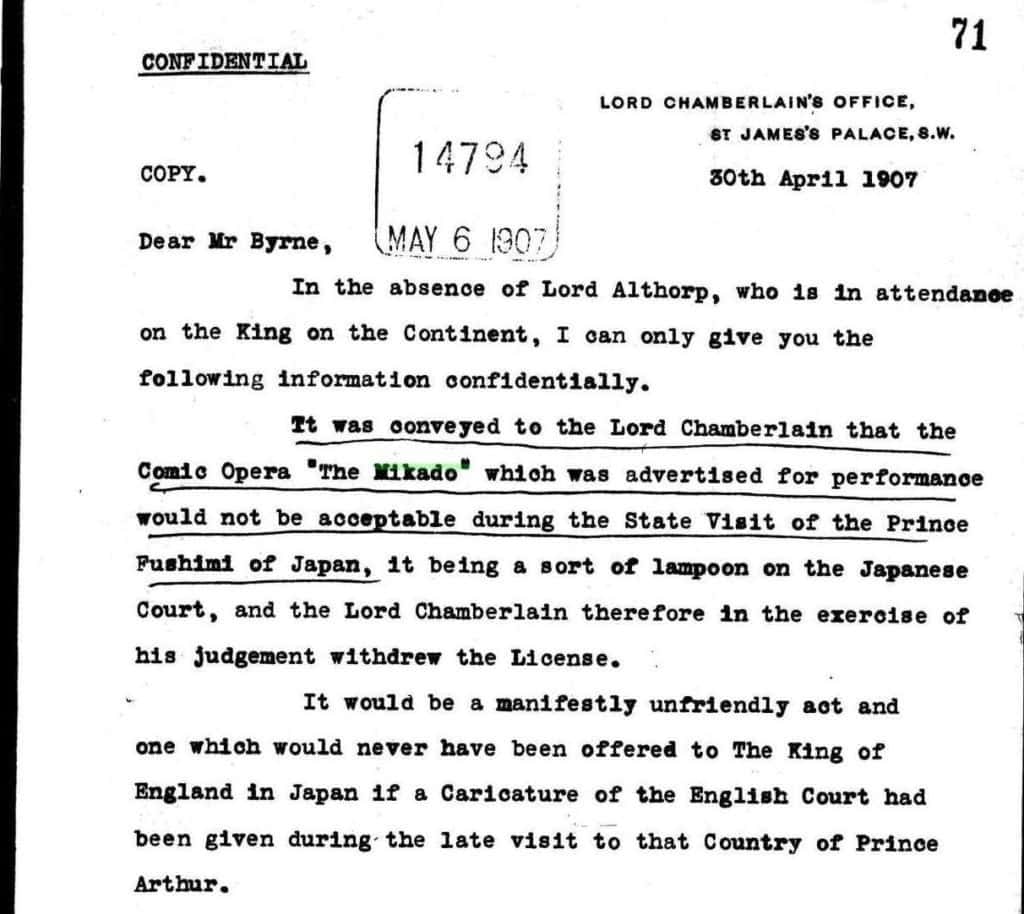

Withdrawn for Diplomatic Reasons

In 1907, during a revival run of The Mikado, Prince Fushimi Sadanaru (1858–1923), a member of the Japanese Imperial Family, visited England on a diplomatic mission. At the time Japan was deemed an important political and military ally of Britain, and the Lord Chamberlain was so worried that The Mikado may offend their honoured guest that they took the extraordinary measure of withdrawing the opera’s license just prior to his visit.

The decision understandably caused an uproar among the opera-going public, with some calling for a petition to be presented to Prince Fushimi himself.

Interestingly, the above article states, “according to a member of his party, the Japanese Prince would certainly not have made any diplomatic representations on the subject.” Similarly, the Daily Mail humorously reports an incident where British naval officers who happened to board a Japanese warship docked in England witnessed the ship’s naval band “insult themselves” by merrily playing the prohibited tunes, which they praised as “quite one of the nicest things of your music”.

Most disappointed of all, of course, was W. S. Gilbert himself, as the ban deprived him of a significant income. In an interview he wryly remarks, perhaps having read the above article, that “the music of ‘The Mikado’ is being played at this moment on the Japanese ships in the Medway.”

![[By the Herald's Special Wire]. “Sir W. S. Gilbert Gives Views on the Censorship.” New York Herald [European Edition], 20 Aug. 1909, p. 3. International Herald Tribune Historical Archive 1887-2013](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/IHT_Gilbert_on_Censorship_HOJEKT514281290_DT.jpg)

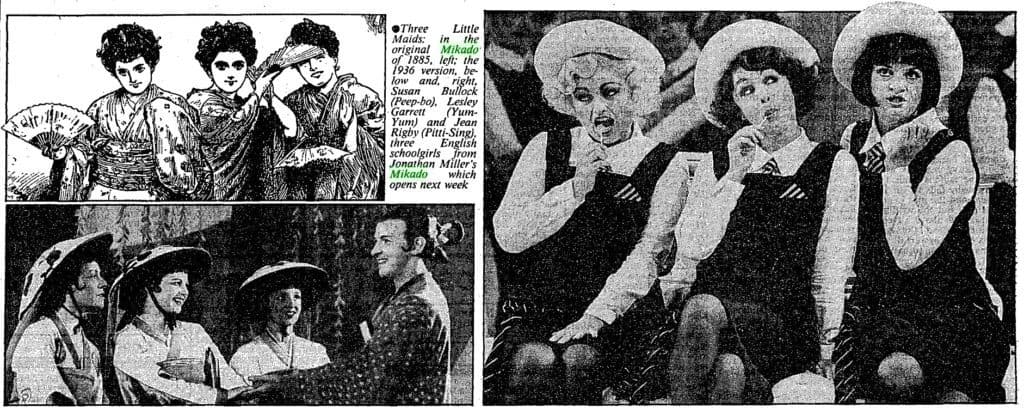

Charles Ricketts’ 1926 production

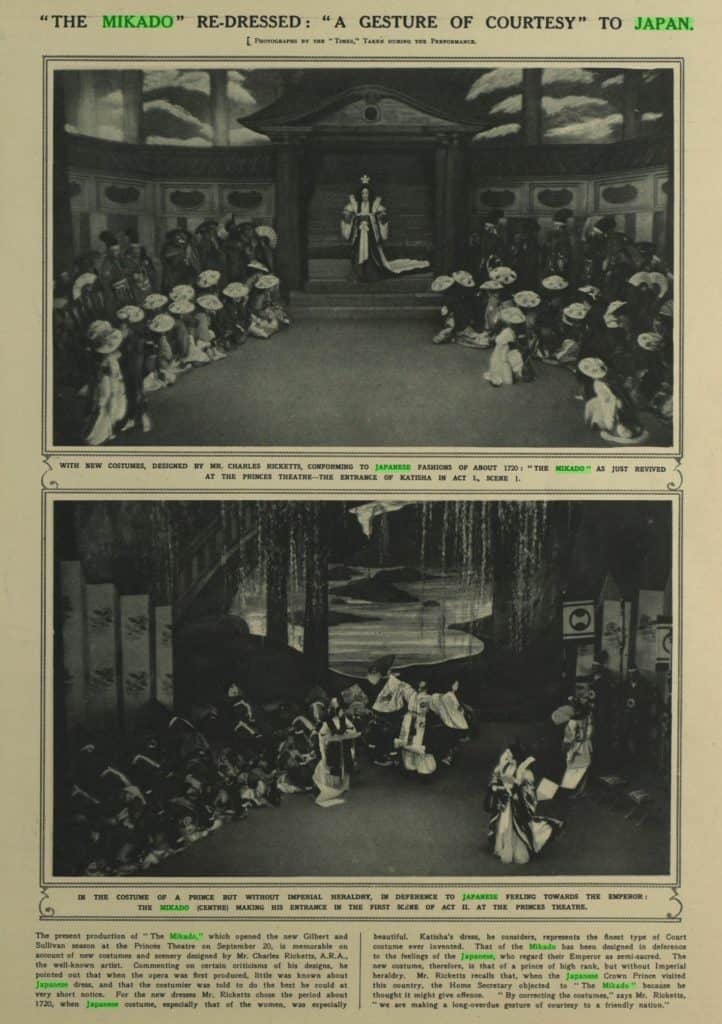

While the 1907 censorship was led by British authorities fearing a diplomatic gaffe, later on it was the stage directors and designers who felt that the opera needed modifying to make it more palatable to modern sensibilities. One attempt was by the stage designer Charles Ricketts (1866–1931), who as the basis for the 1926 production’s costume design “chose the period about 1720, when Japanese costume, especially that of the women, was especially beautiful.” He hoped that “by correcting the costumes, we are making a long-overdue gesture of courtesy to a friendly nation.”.

I am not sure where Ricketts got the idea that 1720 was the peak of Japanese female costume, but even if it was, I feel that the solemn grandeur shown in the photographs is rather incongruous with the light-hearted, tongue-in-cheek spirit of the libretto.

Apparently I am not alone in feeling that he may have missed the whole point, as a contemporary reviewer in Punch writes, “If The Mikado makes a mockery of Japan, how does it help matters to render the costumes more realistic?” The reviewer also states that if W. S. Gilbert were alive then, “he would have put the idea of The Mikado into a wholly different and remoter setting, and that without the slightest damage to the libretto and still less to the music of Sullivan.”

The 1986 Jonathan Miller Production Set in Britain

Sixty years later, another opera director did more or less what the Punch reviewer suggested. The 1986 Jonathan Miller (b. 1934) production of The Mikado ditched the Japan setting entirely, “putting it instead into a Grand Hotel in Britain between the wars”. Miller states, “When you take away the D’Oyly Carte accretions—all those fans and knitting needles—you can see that the Mikado has nothing to do with Japan but everything to do with England, its snobbery, class system, offficialdom.” Very true—but by stripping the opera of its ironic setting and basing it squarely in Britain, doesn’t the humour lose some of its bite?3

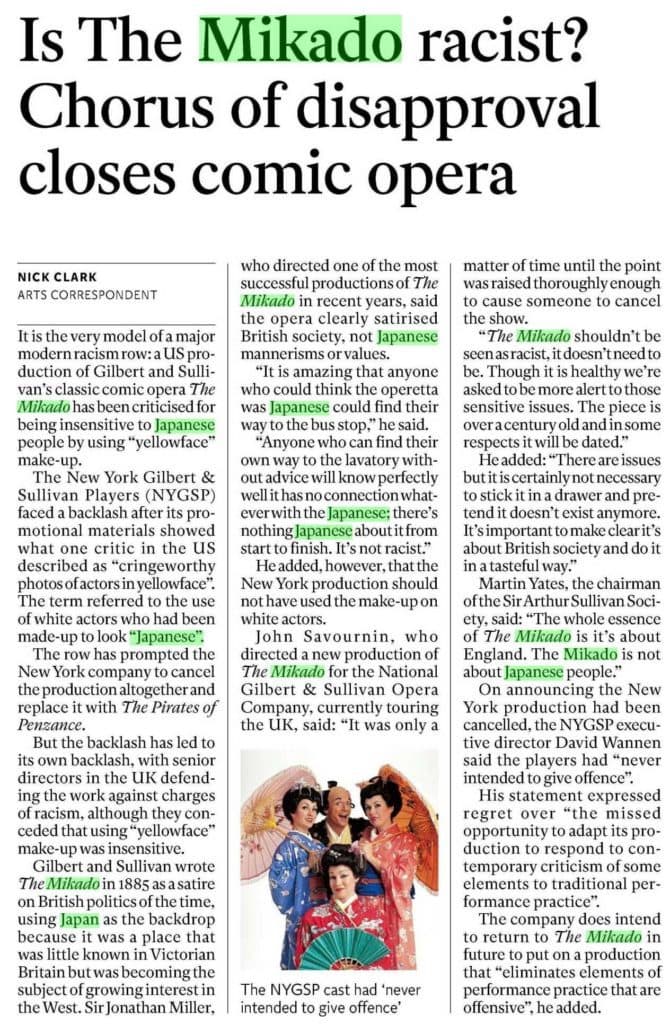

Disapproval of the 2015 New York Production

But nowadays simply reverting to the original kimonos and topknots can prove too hazardous. In 2015, a revival in New York tried it—including skin make-up to make the actors look more “Japanese”—and was forced to close down amid cries of “racism” and “yellowface”. One online essay critical of the production, subtitled “Cultural Appropriation 101”, compares the opera with various xenophobic racist images portraying Asians, and asserts that it is making “jokes at the expense of the powerless”.

Not everyone shared that view. Jonathan Miller, the British director of the 1986 “Grand Hotel” production, sarcastically commented, “It is amazing that anyone who could think the operetta was Japanese could find their way to the bus stop.” It needs to be noted, however, that this was an American production, and that much of the criticism came from the local Asian American community. While as a Japanese residing in Japan I am not offended by the production photos, it is not difficult to imagine how Asian Americans found the racial cross-dressing unbearable, as it may have reminded them of painful incidents of discrimination that they face as a minority in America.

Utilising the Harajuku Esthetic

The United States hasn’t heard the last of The Mikado, however. A recent Los Angeles production once again uses Japanese-inspired costumes, except they are not from 1885, or 1720, but inspired instead by “the Harajuku esthetic in that district of Tokyo famous for its wild mix of colors and styles”. As anyone who has visited the famed Takeshita street in Tokyo would attest, the youthful ‘Harajuku culture’ is a wild mish-mash of east, west, old, modern, everything in between and beyond. In fact, its uniqueness lies in its total disregard of cultural boundaries and traditions. While I cannot comment on the production without having seen it myself, it sounds like an ingenious way to update the opera for the twenty-first century, without rejecting the Japanese setting, and at the same time avoiding the “cultural appropriation” trap. Whether we are British, Asian, American, Asian-American, or members of any other tribe, in the glittery anarchic world of Harajuku fashion we can all become “Gullivers” in a stranger Japan than Swift or Gilbert ever could have imagined.

The writer would like to thank Miyazawa Shin’ichi sensei for introducing to him this topic for this post.

- Koyama, Noboru. London Nihonjinmura wo Tsukutta Otoko: Nazo no Kogyoshi Tannaker Buhicrosan 1839-94. Fujiwara Shoten, 2015.(小山騰『ロンドン日本人村を作った男:謎の興行師タナカー・ブヒクロサン1839-94』藤原書店,2015年)An alternative theory holds that the Frederik Blekman identification is mistaken. For more details please consult Paul Budden’s Paper Butterflies: Unravelling the Mystery of Tannaker Buhicrosan (Gatekeeper Press, 2020).

- It should be noted that Japan also appears in Gulliver’s Travels as the only real location visited by the main character.

- Miller’s Mikado has enjoyed countless revivals since, and remains in performance today (English National Opera, London Coliseum, 22 Nov–30 Nov 2019), so perhaps my judgement is mistaken.