By Dr Alexander Morrison, Fellow & Tutor in History, New College, University of Oxford

The exciting new archive China and the Modern World: Diplomacy and Political Secrets launches this month. This will be the third instalment in the China and the Modern World programme, which covers many aspects of nineteenth- and twentieth-century China, including its international relations, trade, and domestic and foreign policy. Diplomacy and Political Secrets is sourced from the India Office Records at the British Library, and presents a wealth of rare records, gathered by the British, pertaining to the relations among China, Britain, British India, British Burma, Central Asia, Russia and Japan. Below, academic advisor Dr Alexander Morrison discusses one of the influential characters whose career can be traced through these files.

The tentacles of Britain’s Indian Empire stretched far beyond its nominal frontiers throughout the nineteenth century. From the Durand Line in the far North-West, which provided a contested border with Afghanistan, to Hunza, Chitral and the far reaches of the Karakoram range, Ladakh and the Tibetan plateau, the Naga Hills and the Shan and Kachin States of Upper Burma, the formal territory of British India was surrounded by an informal penumbra, where British trade, diplomatic and military influence still penetrated. Much of this lay in the outlying regions of the Qing Empire: Tibet, which was effectively independent and under British protection after 1913, with a British agent at Gyantse from 1904;[1] Yunnan, which bordered British Burma, French Indochina and the buffer-state of Siam between them;[2] and perhaps most fascinating of all, Xinjiang, reconquered by the Qing only in 1877 after a widespread revolt by the region’s Chinese and Turkic Muslim population, and thirteen years of independence under the rule of the Khoqandi adventurer Yaqub Beg (1820-1877).[3]

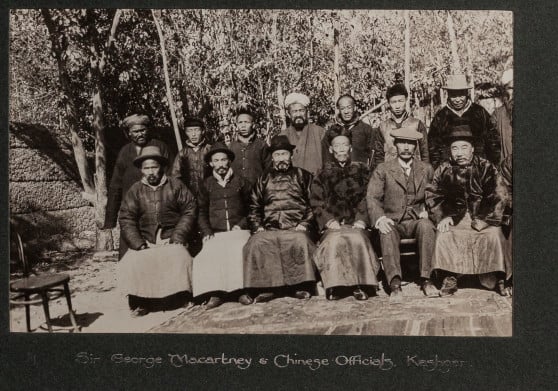

After Yaqub Beg’s death and the return of Qing rule, the remote Central Asian city of Kashgar in Xinjiang became the site of competing British and Russian consular outposts. The best-known protagonist on the British side was Sir George Macartney (1867–1945), the son of a Scottish diplomat and a Chinese noblewoman, born and brought up first in Nanking, and then educated at Dulwich College in London.[4] Arriving in Kashgar in 1890 as part of an expedition led by Francis Younghusband (1863–1942), Macartney was fluent in Chinese, and soon added a good knowledge of Turki. Despite these obvious qualifications, as a mixed-race man from a middle-class background he struggled for recognition within the notoriously snobbish diplomatic service. Though he served in Kashgar from 1890–1918, he was only officially appointed as consul in 1908, something that was a considerable handicap to him in his dealings both with the Chinese and with his Russian counterpart.[5] The latter was the irascible Nikolai Fedorovich Petrovskii (1837–1908), who claimed to have great influence over the Qing authorities in Kashgar despite never learning a word of Chinese.[6] A string of travellers passing through the city were entertained by one or the other of this pair, and many travelogues and memoirs evoke the atmosphere of consular Kashgar in those days, notably that of Macartney’s wife.[7]

Meanwhile, however, Macartney was doing his job, in which he was much more concerned with his relations with the local authorities than with entertaining passing travellers. The record of these day-to-day interactions and communications is found in his correspondence with the British resident in Kashmir (his nominal superior) and with the Foreign Department of the Government of India, held in the Political & Secret files of the India Office. In December 1896, for instance, we find Macartney passing on the objections of the Chinese provincial governor to a map of Kashmir which placed the Aqsai Chin plateau in British territory, having had his attention drawn to this by Petrovskii.[8] Seventy years later the Chinese construction of a road linking Xinjiang and Tibet through this remote, barren, region would become a casus belli of the 1962 Sino-Indian War.[9]

More often throughout the 1890s Macartney was encouraging the Chinese to resist Russian encroachments in the terrain which the latter claimed on the high Pamirs as a result of their annexation of the Khanate of Khoqand in 1876.[10] In December 1891 Macartney wrote to Sir Henry Durand in Kashmir that the Russian authorities had informed the Chinese that the large body of their troops who had occupied the Pamir plateau the previous summer had no official status (this was untrue – it was in fact an official military expedition, led by Colonel Mikhail Efremovich Ionov, which was tasked among other things with removing Chinese boundary-markers in the Pamirs, something which Petrovskii considered needlessly provocative).[11] With the same letter he forwarded his translation of the inscription on a pillar which had recently been discovered at Somatash in the Pamirs – it commemorated a victory by a Qing general over the ruling Khwajas sixty years before, and could potentially have been used to bolster the Chinese claim to the region.[12] Ultimately the Russians did annex much of the Pamir region, pushing aside both Chinese and Afghan claims, and in 1895 a new frontier line was amicably agreed with the British, leaving a sliver of Afghan territory – the Wakhan Corridor – between British India and Russian Turkestan.[13] In 1907 an Anglo-Russian agreement was signed to resolve continued disputes between the two powers in Asia, which did help to ensure that in 1914 Britain entered the Great War against the Central Powers as part of the Entente with Russia.

Nevertheless, tensions remained,[14] and in 1915 Macartney was still proposing a comprehensive agreement to settle continued disagreements over respective British and Russian interests in Xinjiang.[15] Yet his proposal was rapidly overtaken by events when Russian power in Central Asia dissolved in the wake first of the 1916 revolt against Russian rule (which saw a wave of Kyrgyz refugees flooding into Xinjiang), and then of the February and October revolutions in 1917.[16] One of the few things the discreet Macartney published in his own lifetime was an account of his journey home through Central Asia during the turmoil of the Russian Civil War.[17] It was only after 1921 that the Soviets reconquered Turkestan, and only in 1924 that the new regime reasserted control over the former imperial Russian consulate in Kashgar.[18] By then Macartney had gone into a well-earned retirement in Jersey, where he died in 1945 just after the island was liberated from German occupation, and only four years before the Kashgar consulate would close for good as the Chinese Communists moved in after 1949.[19]

SEE ALSO: For digitised primary sources on the earlier George Macartney (1737-1806), British Ambassador to China at the end of the eighteenth century, see The Earl George Macartney Collection in Archives Unbound. This collection features fascinating materials from the Charles Wason Collection at Cornell, including letters, books, sketches and journals relating to the important Macartney mission from George III to the Chinese Emperor Qianlong in 1792–1794.

Blog post cover image citation: Photographs taken by Lt-Col Sir Percy Sykes to illustrate Chinese Turkestan, the Russian Pamirs and Osh. April-November, 1915. IOR/L/PS/20/A119. http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9X9bU1

[1] Alex McKay, Tibet and the British Raj. The Frontier Cadre 1904-1947 (Richmond: Curzon, 1997)

[2] On Anglo-French Rivalry in this region, see Patrick Tuck, The French Wolf and the Siamese Lamb: The French Threat to Siamese Independence, 1858-1901 (Bangkok: White Lotus, 1995)

[3] See James Millward, Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998) & Hodong Kim, Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864–1877 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004).

[4] Katherine Prior, ‘Macartney, Sir George (1867–1945), diplomatist’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004). See further James McCarthy, The Diplomat of Kashgar. A Very Special Agent. The Life of Sir George Macartney (Hong Kong: Proverse, 2014).

[5] The standard account of his career there is Clarmont Percival Skrine & Pamela Nightingale, Macartney at Kashgar: new light on British, Chinese and Russian activities in Sinkiang, 1890-1918 (London: Methuen, 1973).

[6] On the Russian presence in Kashgar at this time, see Aleksandr Kolesnikov, Russkie v Kashgarii. Missiya, Ekspeditsiya, Puteshestviya (Bishkek: Raritet, 2006); much of Petrovskii’s correspondence has been published as N. F. Petrovskii, Turkestanskie Pis’ma ed. V. S. Myasnikov (Moscow: Pamyatniki Istoricheskoi Mysli, 2010)

[7] Lady Catherina Theodora Macartney, An English Lady in Chinese Turkestan (London: Ernest Benn, 1931).

[8] ‘Memorandum of Information received in December 1896 Regarding the North-West Frontier of India’. IOR/L/PS/7/90-2 pp.5-6

[9] ‘Informal Note of the Indian Government (Aksai Chin)’, 18/10/1958, Notes, Memoranda and letters Exchanged and Agreements signed between The Governments of India and China 1954 –1959 (New Delhi: Ministry of External Affairs, 1959) pp.26-8. On the parallel border dispute in the Eastern Himalayas see Bérénice Guyot-Réchard, Shadow states: India, China and the Himalayas, 1910-1962 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[10] S. C. M. Paine, Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and their Disputed Frontier (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1996) pp.272-4; Scott Levi, The Rise of Khoqand 1709–1876. Central Asia in the Global Age (Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh UP, 2017) pp.188-209.

[11] Petrovskii to Osten-Sacken 05/10/1891; Petrovskii to Osten-Sacken 25/10/1891, Turkestanskie Pis’ma, pp.220, 222. Ionov also encountered and removed Francis Younghusband, who gave a celebrated account of the incident in his memoir: Francis Younghusband, The Heart of a Continent, A Narrative of Travels in Manchuria, Across the Gobi Desert, through the Himalayas, the Pamirs, and Hunza 1884–1894 (London: John Murray, 1896), pp.293-4.

[12] Macartney to Durand 05/12/1891. IOR/L/PS/7/65-Sec.No.41 p.919

[13] M. G. Gerard, Report on the Proceedings of the Pamir Boundary Commission (Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Govt Printing, 1897)

[14] See Jennifer Siegel, Endgame. Britain, Russia, and the Final Struggle for Central Asia (London: I. B. Tauris, 2002)

[15] ‘Chinese Turkestan. Memorandum by Sir George Macartney, K.C.I.E, suggestions for a convention between Britain and Russia, regarding the Chinese province of New Dominion [Xinjiang]’ 23/08/1915. IOR/L/PS/18/A172 pp.1-5.

[16] Marco Buttino, ‘Central Asia (1916–20): A Kaleidoscope of Local Revolutions and the Building of the Bolshevik Order’, The Empire and Nationalism at War, ed. Lohr, Tolz, Semyonov & von Hagen (Bloomington, IN: Slavica, 2014), pp.109-136.

[17] G. Macartney, ‘Bolshevism as I saw it at Tashkent in 1918’, Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, Vol.7 Nos.2-3 (June 1920) pp.42-58.

[18] Paul Nazaroff, Moved On! From Kashgar to Kashmir (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1935) pp.115-6.

[19] On the inter-war history of the British consulate at Kashgar and its eventual closure see Max Everest‐Phillips, ‘British consuls in Kashgar’, Asian Affairs 22/1 (1991) pp.20-34.