By Paula Maher Martin, Gale Ambassador at NUI Galway

Read this blog in Spanish here

‘A picture drawn from the life of a people whose days are spent under the sky in the open country’. These are the linguistic contours with which Edith Somerville, in examining P.W. Joyce’s 1909 work English as We Speak it in Ireland, denominates the Anglo-Irish dialect, and accommodates a microcosm of Ireland – an exuberant landscape and a people intoxicated with nature, feeling, magic and alcohol.

In consonance with the imperialistic discourse of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, British literary reviews came to read and interpret Irish literature as a self-aware expression of national identity and thus as intrinsically political. The Irish, presented as shrouded in myth and fantasy, emotionally unstable and unable to control and govern themselves, necessitate, for their own welfare, British authority.

Somerville, Edith Anna. “The Anglo-Irish Language.” The Times Literary Supplement, 5 May 1910, p. 157+. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TSjTX. Accessed 23 April 2018.

“The Late Mr. Dion Boucicault.” Illustrated London News, 27 Sept. 1890, p. 387. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TRq56. Accessed 30 April 2018

An 1872 piece in the Penny Illustrated Paper on Dion Boucicault’s Arrah-Na-Pogue, highlights the emotional nature of the Irish. Shaun, the character portrayed by the author in this play, resolves to escape the unjust incarceration to which for love he has subjected himself upon hearing the song of his lover, Arrah: ‘he ‘is’ no commonplace fellow evading his sentence, but a lover who would again look on the face of her he loves at the risk of almost certain death’. After many tribulations, animated by love and vengeance, at the end of the melodrama ‘everybody is mad happy, including the audience, whose glistening eye, liberal use of handkerchief and opera-glass… bear witness to the pleasure derived from the performance’.

“ARRAH-OF-THE-KISS.” Penny Illustrated Paper, 8 June 1872, p. 364+. British Library Newspapers, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTFCX. Accessed 30 April 2018.

Aside from their sentimentality, Boucicault’s Irish display an intrinsic gift for humour, an ability to playfully manipulate a linguistic framework which is not quite their own. The dialogue of Arrah-Na-Pogue is replete with ‘those Hibernian gems – phrases where the direct absence of logic is more powerful, expressive, and truthful than logic itself‘.

“The Late Mr. Dion Boucicault.” Illustrated London News, 27 Sept. 1890, p. 387. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TRq56. Accessed 30 April 2018

Ireland is also painted with a veil of fantasy and arcane spirituality. A review of WB Yeats’ poem ‘The Wild Swans at Coole’ portrays him as a fiddler whimsically caressing the chords of his instrument. Yeats’ verses encapsulate for the reviewer the idealism of the Irish spirit and the visionary quality of their language, seeming to transcend words, operating in the realm of music. Literature in Ireland reflects a distance from reality, which the Irish appear to regard through a ‘magic and isolating medium of their own’. And yet, in another discussion of Yeats’ The Celtic Twilight, Andrew Lang observes that the rusticity of the Emerald Isle warrants this distance: its mysticism and convivial relationship with the “Fairy Commonwealth”, ‘as newspapers and education come slower up that way’; the romantic myth of Ireland gradually dissolves.

Lang, Andrew. “Irish Fairies.” Illustrated London News, 23 Dec. 1893, p. 802. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTEk0. Accessed 15 April 2018.

However, at other times, the press underlines the fierce, roguish aspect of the Irish soul, in an echo of the tense political milieu and the threat of Irish Home Rule. Qualities, “common to all” Irishmen are transpired in Hibernian literature; wild and impulsive, Irish authors through the ages ‘were rich in imagination and fluent of pen; they had individuality, irrepressible vigour and the Gallic verve and esprit’, claims a Times Literary Supplement 1902 article on the anthology The Cabinet of Irish Literature.

Shand, Alexander, and A. I. Shand. “Irish Literature.” The Times Literary Supplement, 15 Aug. 1902, p. 241. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTBE4. Accessed 23 April 2018.

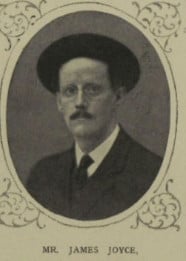

At the turn of the century, some reviews harbour overtly political statements. A 1914 analysis of James Joyce’s Dubliners defines the work as a kaleidoscopic collection of facts where ‘the sentimental Irishman of the English fancy is, of course, absent’: manipulated by Church and State, Joyce’s Dubliners are ‘drab, rather dirty minded, rather suspicious, and superstitious materialists’. The romanticized Ireland, of saints and scholars, fairies and minstrels vanishes and its subjects emerge as ‘a people who have lost the self-respect of freemen- a people. to put it clearly, ripe for Tammany.’ – ripe for defiance of the lawful rule of the British Empire.

“Novels.” Literary Supplement. Illustrated London News, 1 Aug. 1914, p. III. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTF29. Accessed 27 April 2018.

Read this blog in Spanish here

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“ARRAH-OF-THE-KISS.” Penny Illustrated Paper, 8 June 1872, p. 364+. British Library Newspapers, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTFCX. Accessed 30 April 2018.

Clutton-Brock, Arthur. “Tunes Old and New.” The Times Literary Supplement, 20 Mar. 1919, p. 149. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTCg6. Accessed 30 April 2018.

“Dion Boucicault”. Penny Illustrated Paper, 8 June 1872, p. 364. British Library Newspapers, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6Tqcc5. Accessed 30 April 2018.

Lang, Andrew. “Irish Fairies.” Illustrated London News, 23 Dec. 1893, p. 802. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTEk0. Accessed 15 April 2018.

“Novels.” Literary Supplement. Illustrated London News, 1 Aug. 1914, p. III. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTF29. Accessed 27 April 2018.

Shand, Alexander . “Irish Literature.” The Times Literary Supplement, 15 Aug. 1902, p. 241. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6TTBE4. Accessed 23 April 2018.