│By Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull, Senior Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford│

Researching literary manuscripts is difficult. In the years following their production, primary sources have often been spread across different institutional libraries around the world. This makes accessing them complicated and expensive, particularly for early career researchers and those conscious of the impact that travelling large distances has on the environment. But thanks to Gale’s British Literary Manuscripts Online, this can be avoided. This resource is home to digital facsimiles of over 4,500 manuscripts created between c.1120-1900. Although the originals are now housed in institutions across the globe, Gale’s archive allows you to view many from the comfort of your own home. Read on for tips of how to get the most out of this digital resource of fascinating primary sources and enhance your academic research.

1. Familiarise Yourself with the New Interface

British Literary Manuscripts Online recently migrated to the Gale Primary Sources platform. This means that the user interface has been improved to make it more user friendly. If you’ve previously used this archive for your research, you might want to take a few minutes to familiarise yourself with the updated version. And don’t panic. If you’ve used any of the other primary source databases from Gale, such as Eighteenth Century Collections Online, you’ll be a natural, as both resources now use the same interface!

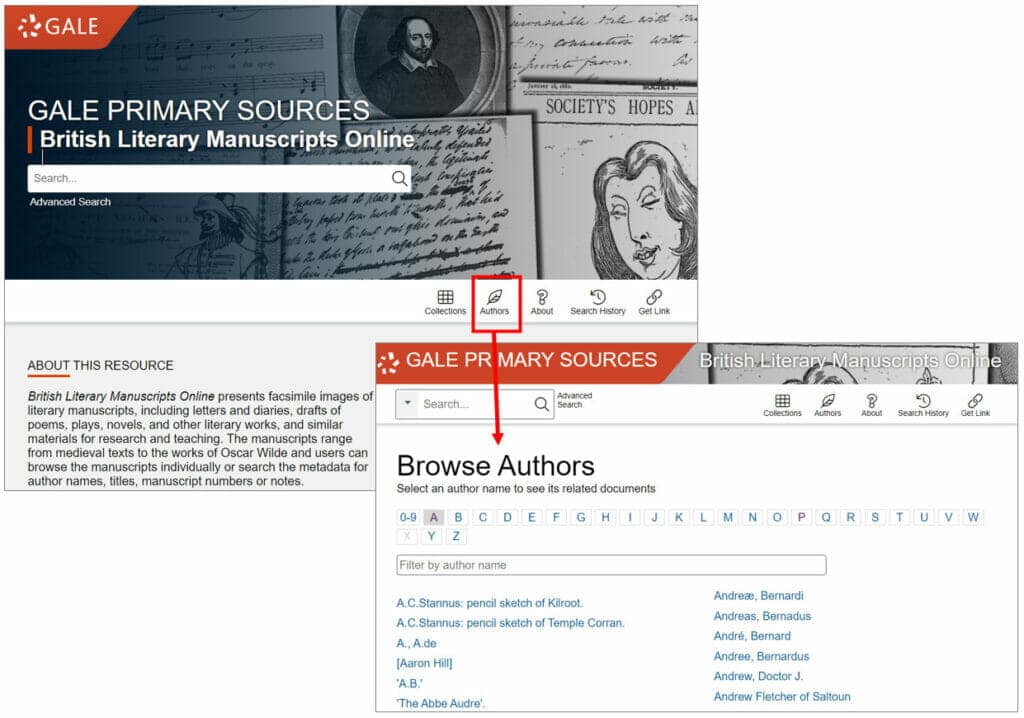

2. Play Around with the ‘Browse Authors’ Feature

One of the new features in the latest update of this resource is that you can now browse by author. This is invaluable for quickly checking which primary sources have been digitised relating to your author(s) of interest, and thus for helping you decide which libraries you may need to still visit in person to see other manuscripts of their work.

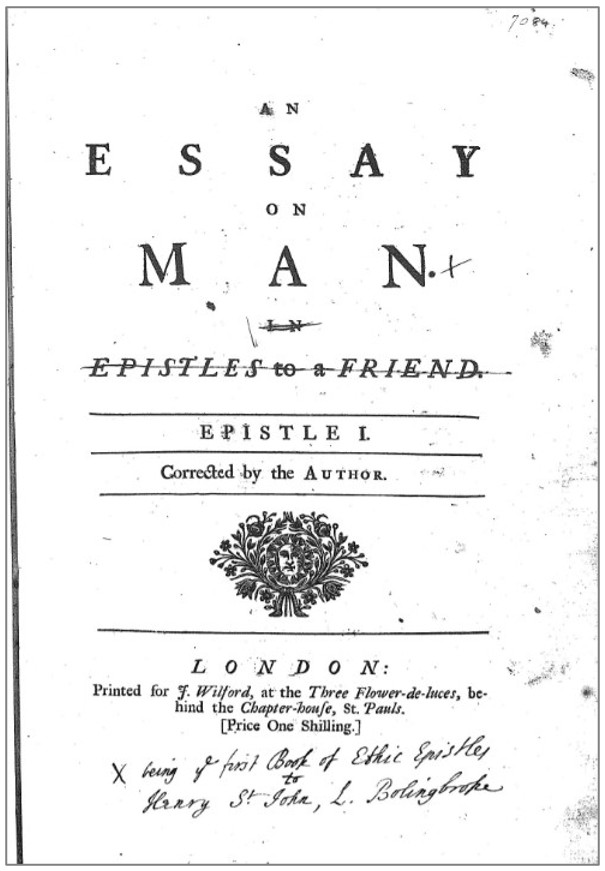

3. Expand your Definition of Manuscript

In addition to its collection of manuscript digital facsimiles, this database also contains a wealth of annotated printed books. This makes British Literary Manuscripts Online a valuable resource for locating primary sources relating to how authors edited their work. For example, from the annotated author copy below of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Man (1733-4) we can see how he decided to revise the title of his influential poem even after it had reached print publication, and corrected printers errors in preparation for a new edition.

Pope, Alexander: An Essay on Man in Epistles to a Friend. Four ‘Epistles.’ Forster Collection Forster MS F.44.M.14. National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum. British Literary Manuscripts Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MC4400002369/BLMO?u=oxford&sid=bookmark-BLMO&xid=47735324&pg=2

4. Compare Manuscripts to Printed Texts Across Gale Primary Sources

Another way to understand how texts changed over time is to compare manuscript and print variants of the same text available across different Gale Primary Sources archives. For example, you can compare the manuscript of Jonathan Swift’s Memoirs Relating to the Change in the Queen’s Ministry (1711) to the printed edition available in Eighteenth Century Collections Online – helping you to discover variants invaluable for understanding textual evolution.

Indeed, this was a valuable exercise I have utilised when teaching undergraduate students – which you can read more about here. Access to digital versions of manuscripts is invaluable when it’s not possible to get students handling physical copies, as was the case during the pandemic.

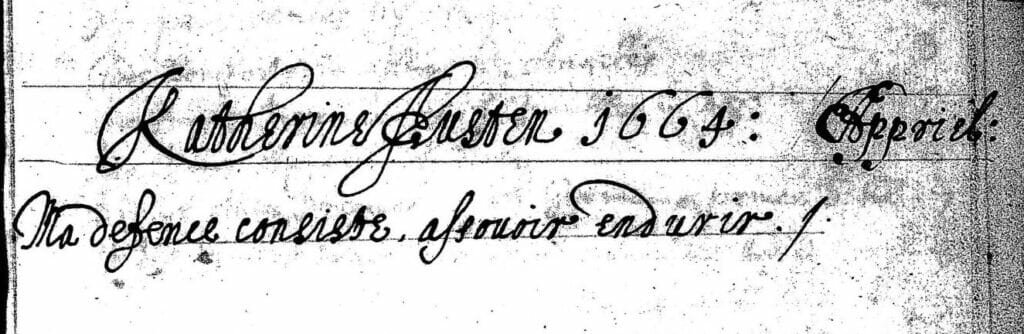

5. Explore Women’s Manuscripts

British Literary Manuscripts Online is home to a rich range of handwritten documents produced by women. This makes it a great resource for researching the literary history of gender all the way from the early medieval to Victorian period. One of my personal favourite primary sources in this category is Katherine Austen’s “Book M”, a rich collection of meditations, journal entries, and poetry written by a powerful widow in the mid-seventeenth century. If you’re interested in women’s writing of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, you might also like to check out the extensive collection of Anna Seward’s writings digitised from the National Library of Scotland.

Katherine Austen, “Book M”, British Library, Add. MS 4454, British Literary Manuscripts Online https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MC4400000069/BLMO?u=oxford&sid=bookmark-BLMO&xid=be4dd232&pg=2

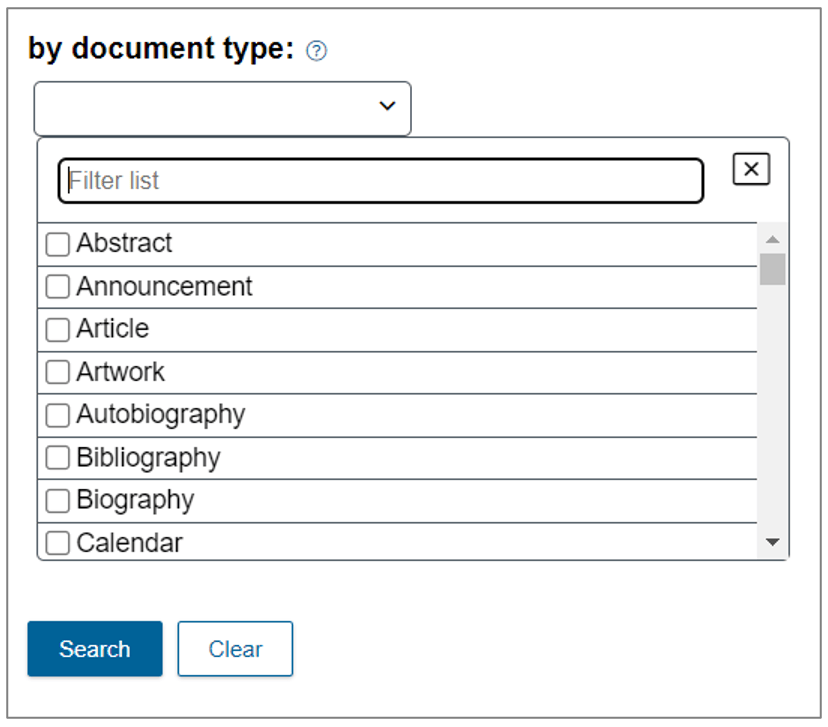

6. Search By Document Type

If you’re interested in researching a particular type of document, you can easily narrow down your results using Gale’s ‘Advanced Search’ functionality. Simply choose as many relevant options listed under ‘Document Type’ in the search limiter, or search for the genre you’re looking for, and the platform will pull through what you’re looking for! There are plenty on offer, so why not include a wide range and expand the scope of your research?

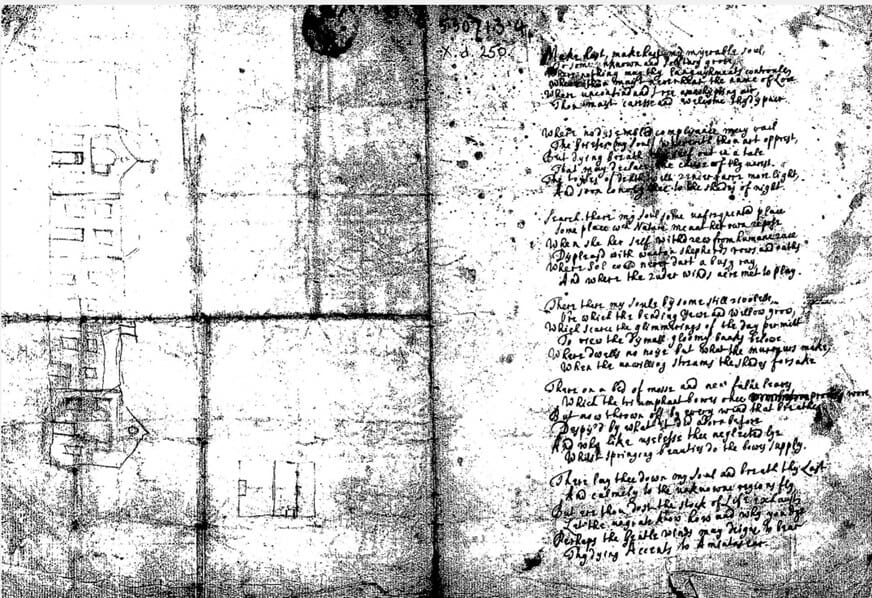

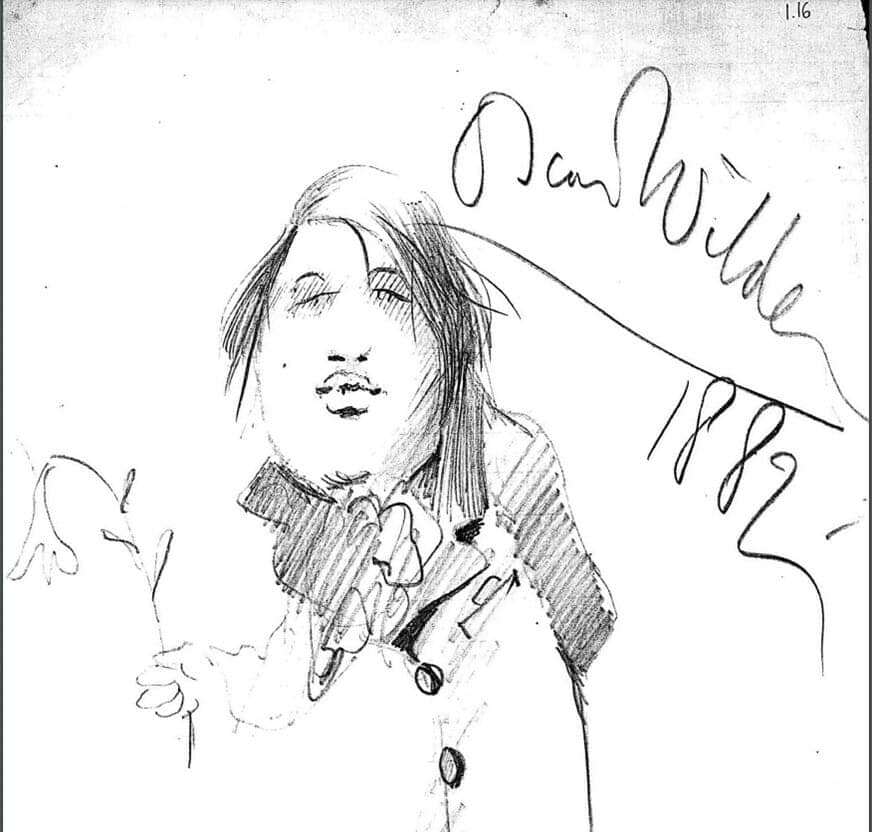

7. Think about Artworks

Authors often included doodles and illustrations in their manuscripts. Gale has helpfully digitised these alongside the written text, helping to shine an important light on how these items were used and read – from doodles of houses in seventeenth century poetic miscellanies, to caricatures of Oscar Wilde on loose sheets of paper that have made their way into larger collections.

Aphra Behn, ‘Make Haste, Make Haste, My Miserable Soul’, Folger Shakespeare Library, Folger MS X.D. 250. British Literary Manuscripts Online https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MC4400003347/BLMO?u=oxford&sid=bookmark-BLMO&xid=de45b07d&pg=1

Unknown Artist, “Caricature of Oscar Wilde Holding a Flower”, Wildeiana Book 1.16, Image 24.5, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, California, British Literary Manuscripts Online https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MC4400002673/BLMO?u=oxford&sid=bookmark-BLMO&xid=6735f7f0&pg=1

8. Look Beyond the Literary

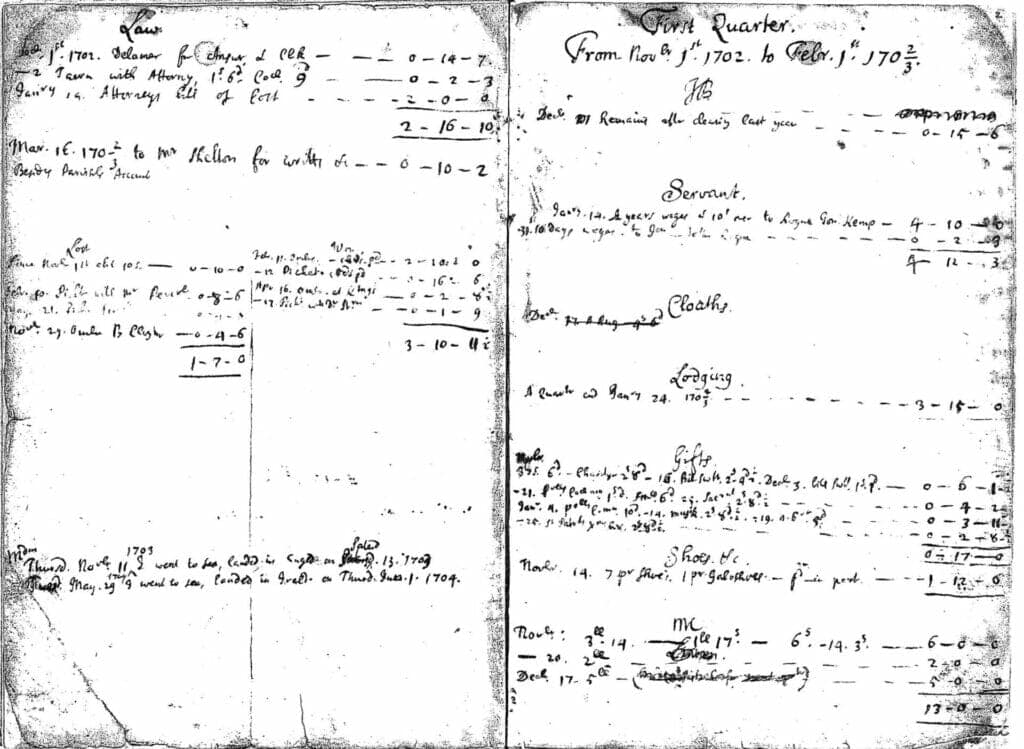

British Literary Manuscripts Online has something for everyone, even those out there who aren’t literary scholars! Many would not realise, for example, that it offers a fascinating range of primary sources of interest to researchers working in areas such as economic history, including manuscript account books, such as those of Jonathan Swift from 1702-3, which help us understand how those of the middling classes managed their money at the turn of the eighteenth century.

9. Think about Textual Transmission

In addition to a range of authorial manuscripts, British Literary Manuscripts Online also allows scholars to access scribal copies of texts. This allows you to trace a text’s popularity over time, counting how often a text appears across a document type such as miscellany, or how late it continued to be copied, indicated by the estimated date of creation.

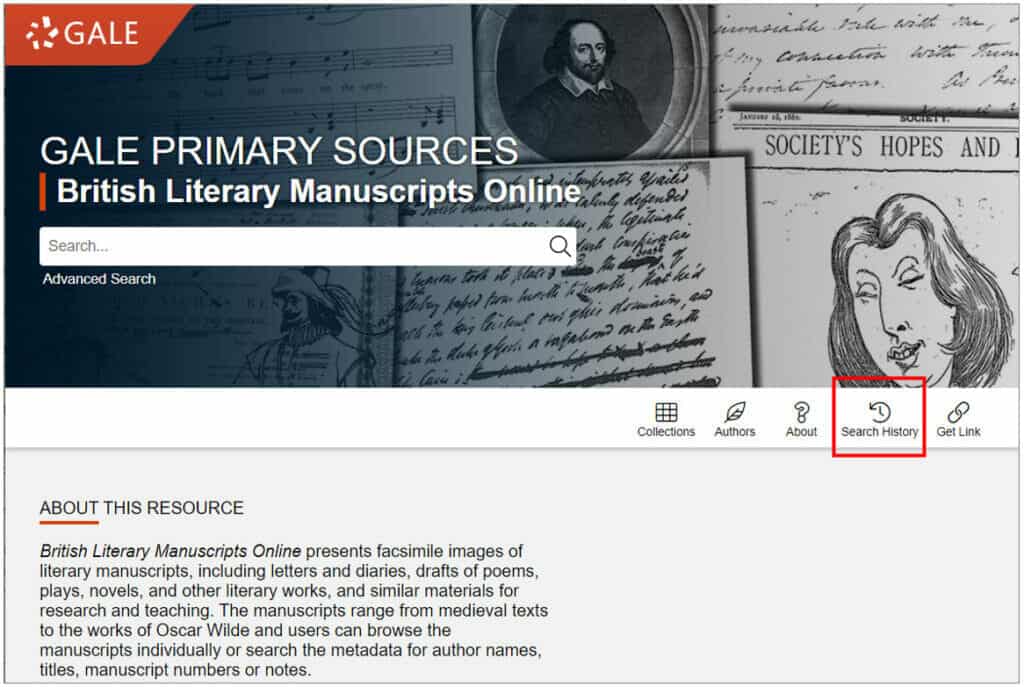

10. Make Use of Your Search History

If you’re anything like me, you’ll easily forget the search terms you’ve used to locate primary sources relevant to your research. This is where Gale’s ‘Search History’ functionality comes to the rescue! Simply click this option, found just below the search bar, and you’ll find a list of the searches you’ve run in that session; helping you to easily re-find your documents.

There’s Always Something New to Find!

Gale’s British Literary Manuscripts Online offers scholars at all career stages a rich and accessible database of primary sources to utilise in their research. Every time I use it, I find something new and interesting to include in my work. And after reading this blog and gaining a better understanding of how to use this resource in your projects, I hope you do too!

If you enjoyed reading about British Literary Manuscripts Online, check out:

- Tracing the Legacy of William Blake with British Literary Manuscripts Online

- PhDing in a Pandemic: The Impact of COVID-19 on Research and Teaching

For more tips on getting the most out of primary source research and the tools in Gale Primary Sources, check out:

- How To Handle Primary Source Archives – University Lecturer’s Top Tips

- An Undergraduate’s Companion: Finding Primary Sources Using Gale’s Alternative Search Tools

- Why Use Primary Sources?

- Top Ten Tips for Teaching with Primary Sources

Blog post cover image citation: Charles I, Letter from Charles I to Prince Rupert 14.6.1644 (Forster MS F.48.G, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, London). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MC4400002473/BLMO?u=oxford&sid=bookmark-BLMO&xid=11d04b54&pg=2