│ by Kyle Sheldrake, Strategic Marketing Manager – Insight and Development │

Primary sources are a valuable resource in research projects, and digitised primary sources combine two advantages: the speed of identifying sources via targeted searching with having thousands of sources at your fingertips whenever they’re needed. The process of creating our Long Read on the Berlin Wall reminded me a lot of the essay writing process at university, so I thought this would be a good example to explain how to break down the process of gathering and assessing primary source material for a research piece, as this may be helpful to our student readers looking to incorporate primary sources into their essays.

ONE: ESTABLISH THE NARRATIVE

The first step is establishing the narrative, and for this I used a few sources from Gale eBooks. Although there wasn’t one search result that covered the complete story, taking sections from a few different eBooks formed a more detailed overview and gave me ideas for areas to explore further with primary source material. I suppose this is the equivalent of the essay advice you hear in your early days as an undergraduate: start with your conclusion and work backwards (or maybe that was just my lecturers?) By starting at the end, it helped identify the important events or landmarks in the story before jumping into the next step.

TWO: ASSEMBLE YOUR LONGLIST

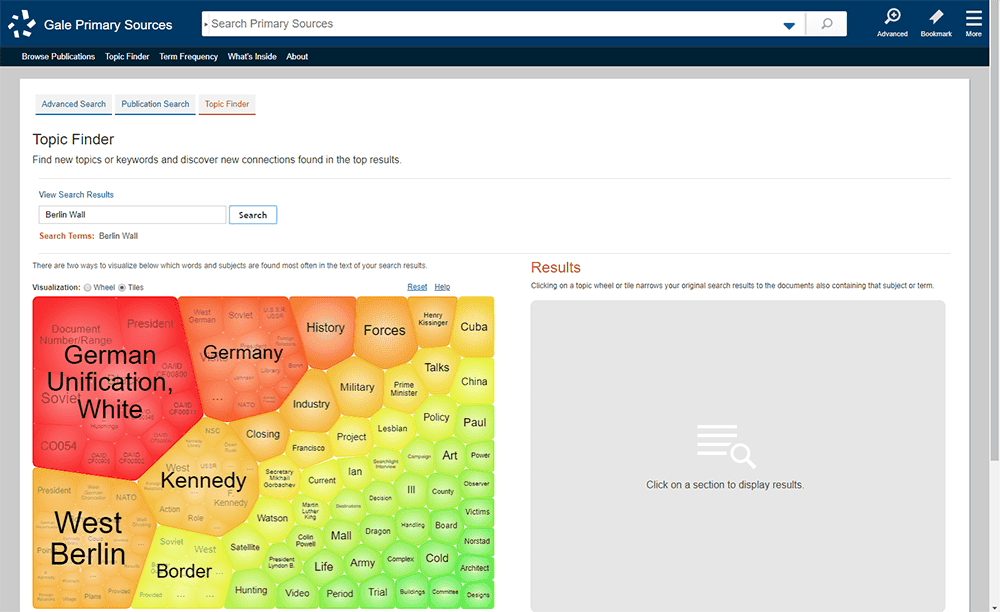

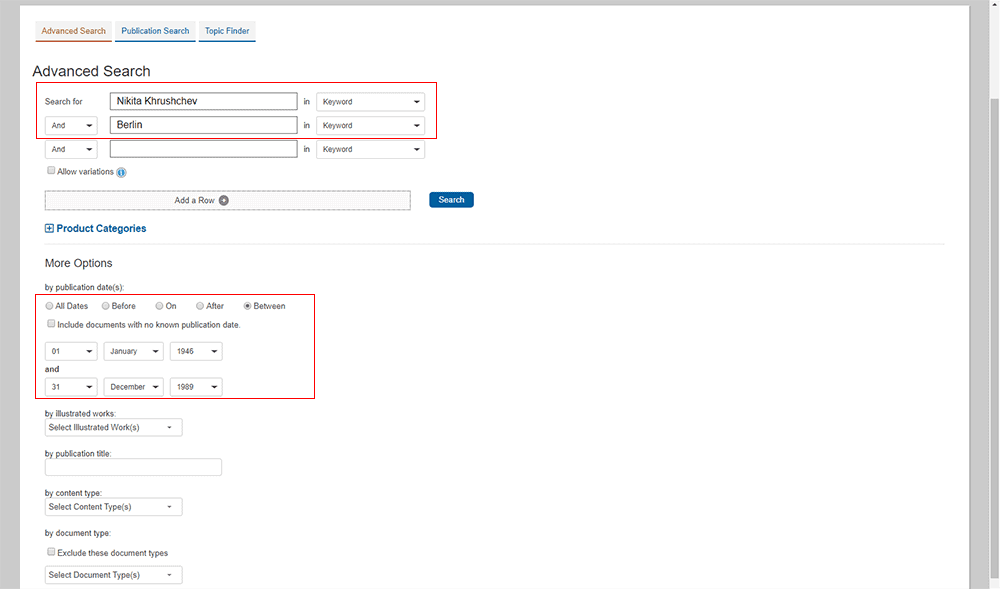

With the prominent elements of the story in hand, next it’s time to create a list of search terms associated with them. It’s best to have a broad range and gather as many sources as you can. A great thing about working with primary sources is the journey has not already been determined, whereas secondary sources have already been focused on a topic or theme. The more sources you have, the more interesting links you are likely to find. The Topic Finder tool in Gale Primary Sources is particularly helpful for identifying connections that would take hours of reading to find; and using advanced search techniques increases the relevance of your results. Some of the advanced search techniques used for the Berlin Wall piece were:

- Filtering the date range (anything before 1945 will not be relevant)

- Using Boolean operators (to find articles that only contain multiple terms – for example “Nikita Khrushchev” and “Berlin”)

- Cross-searching for articles across multiple archives simultaneously (which is a huge time-saver).

This project focused on the way newspapers presented the story of the Berlin Wall to readers, so most of the sources were drawn from newspaper archives (using another search filter: publication type). On the other hand, limiting research to one type of archive can cut out a lot of valuable content. For example, official government documents in U.S. Declassified Documents Online reveal ‘behind closed doors’ information that was not available to the media, giving researchers a chance to compare official state accounts with what the public were told.

There is also the issue of images. Due to the type of paper used for newspapers, the images typically don’t scan very well, so photographs (especially pre-computers when newspapers didn’t have digital production) have poor contrast and don’t work well. This is a good point to explore images in eBooks and database products (or, as I ended up doing, finding images through royalty free or Creative Commons stock photography sites).

This stage creates a longlist of articles on topics you are covering in the research piece, and you can use it to begin constructing the primary source architecture of the project.

THREE: KILL YOUR DARLINGS

If you’ve read as many copywriting books as I have, you frequently see the phrase “kill your darlings.” There’s no avoiding it: your article long list needs the same treatment. Creating the long list takes a long time, so it can be difficult getting rid of articles from the list. Culling the list doesn’t necessarily mean that the work creating the long list goes to waste – this process can provide some interesting ideas for spin-off sections, like the cultural legacy or important figures, if you realise that the culled articles form thematic groups.

And it may be easier to cull some articles which are a lot less relevant. The issue with any system based on keyword searching is that it doesn’t recognise the context the search term appears in, just the occurrence of the words (I dream of the day that semantic searching can do this part as well…) With this limitation, you do need to get reading, and reduce the list of articles down to the most relevant ones. For example, searching for “Berlin Wall” returns articles like this one, which uses the phrase to describe the demolition of a wall built by a man to annoy his neighbour.

FOUR: BACK TO THE FUTURE

With the primary source work done, it’s time to circle back to step one and supplement the core narrative and the primary sources with other secondary sources including reputable websites, books, and journals. This isn’t repeating step one, it’s using the things you have found in steps two and three to identify areas where the primary sources haven’t given enough depth and fill the piece out with some secondary sources. Just like writing an essay assignment, this second pass of secondary sources adds depth to the argument and demonstrates the skill and judgement used in the selection of the primary sources.

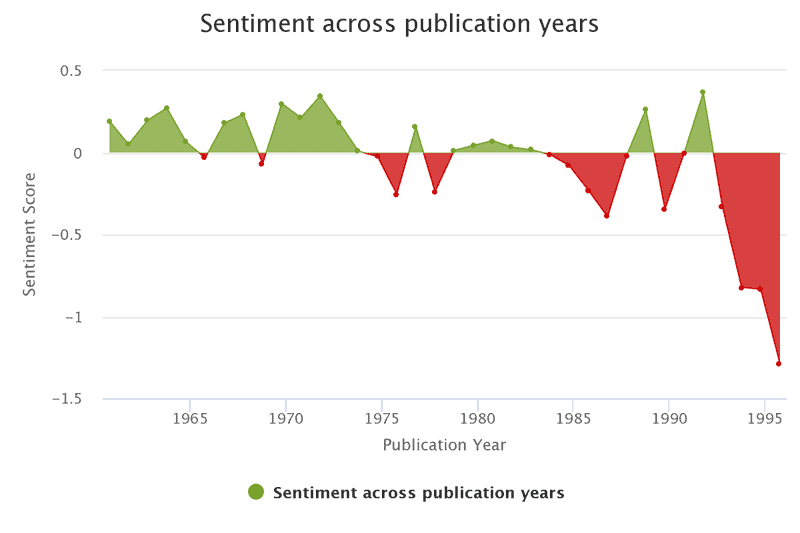

FIVE: LET’S GET DIGITAL, DIGITAL (HUMANITIES)

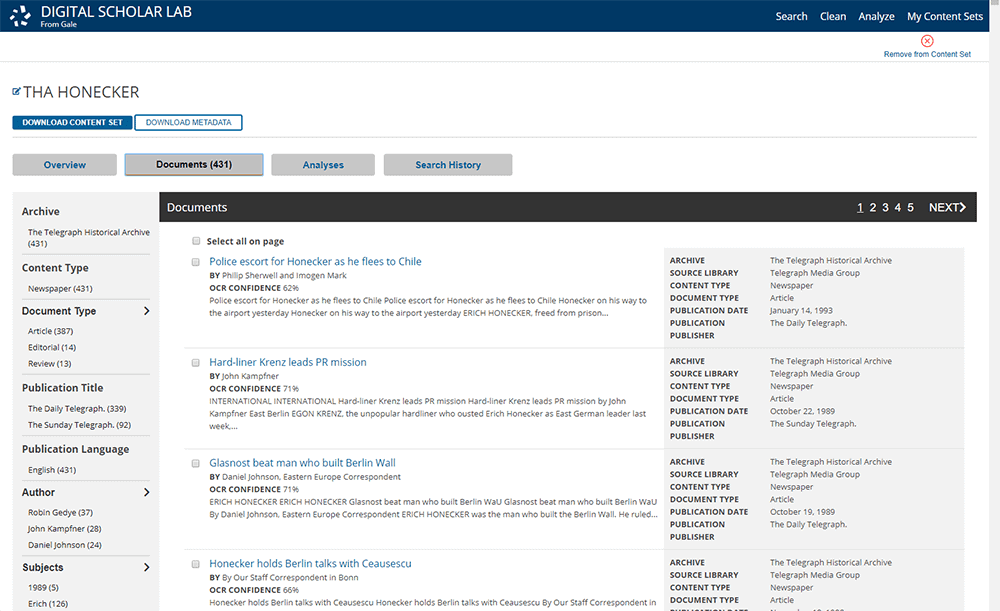

Researchers, including student researchers, with access to the Gale Digital Scholar Lab at their institution can also expand the project with various computational analysis tools to support and elaborate on central ideas. In this project, I used a sentiment analysis to graph the media presentation of the important figures based on the positive and negative presentation and show how it shifted over time. The process was simple, so simple that a digital humanities amateur could do it. Within the Lab I could create and save a content set, run it through a sentiment analysis, and download a visualisation, all in the space of a few minutes.

The best piece of advice I can offer for those exploring the Lab is to make sure the analysis you run is suited to the project – looking at sentiments expressed toward important figures reveals interesting patterns in media representation, but other analyses might not be so relevant.

Good luck incorporating primary sources into your projects!

Blog post cover image citation: Laptop on desk book stacks (cropped), by @fredmarriage via Unsplash [Creative Commons]