|By Emery Pan, Gale Asia Associate Development Editor in Beijing |

The year 2023 marks the tenth anniversary of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). A decade ago, Chinese President Xi Jinping proposed the “Silk Road Economic Belt” and the “Twenty-first Century Maritime Silk Road” in September and October 2013, respectively, which have since evolved into what is now known as the BRI.

The Concept of the Silk Road

The concept of the BRI drew inspiration from the ancient Silk Road, a network of trade routes that were first formed during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). The road started from present-day Xi’an, passed through Gansu and Xinjiang, entered Central Asia, and eventually reached Europe, connecting China with the rest of the world.

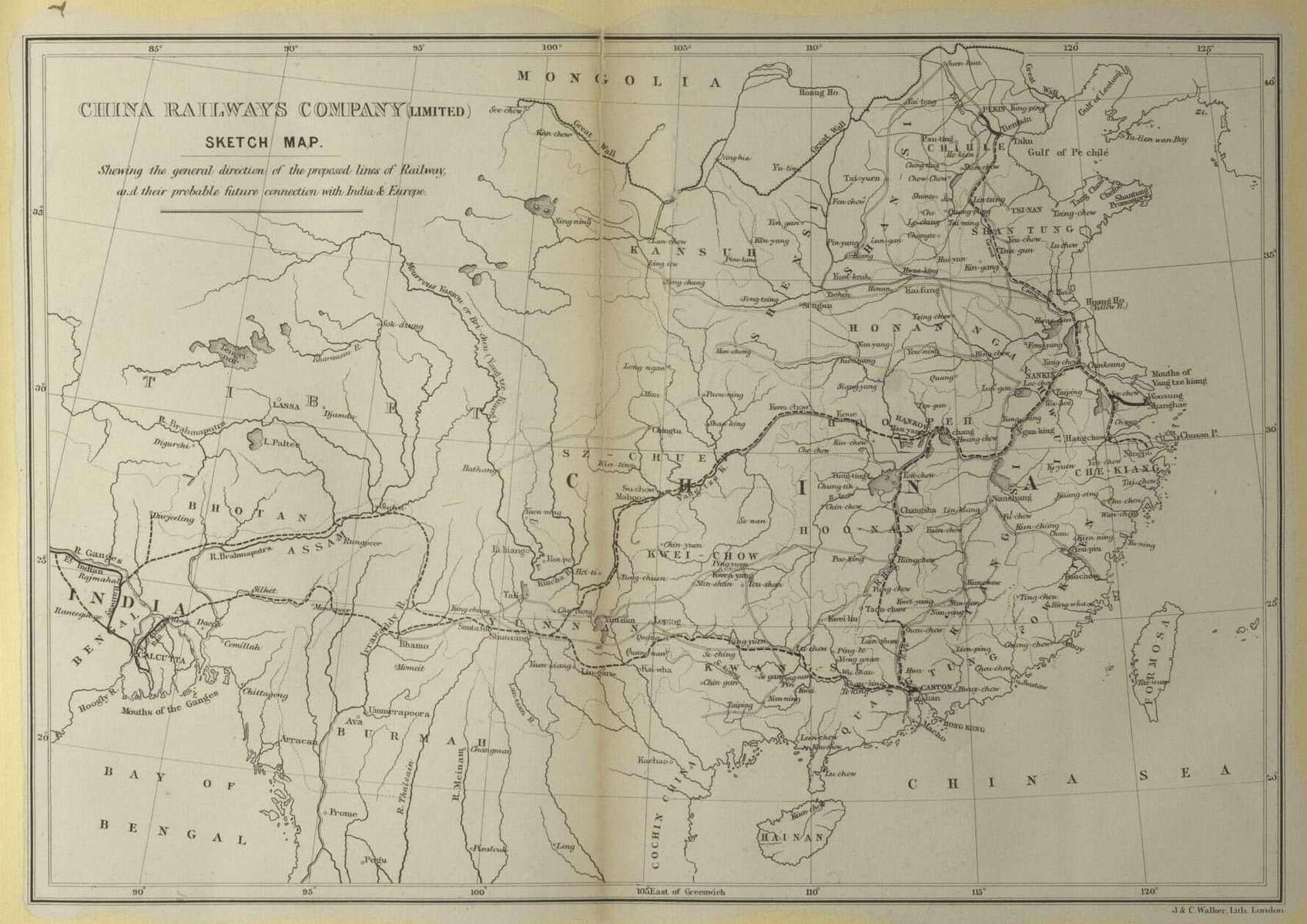

Interestingly, it was not until 1877 that the term “Silk Road” was coined by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen. In an article published in The Geographical Magazine titled “Land Communication between Europe and China,” von Richthofen proposed the construction of a railway from Xi’an to Yining via Hami, outlining an extended rail transport route linking China with Europe. This envisioned railway closely matched the ancient Silk Road.

In the article, he wrote, “The importance of adopting the foregoing suggestions as to the question of railway communication between Europe and China is such as it would be difficult to estimate too highly … The political and purely commercial results of such an undertaking, of course, lie beyond the scope of the present paper. But the effects of the bridging over the vast expanse between the eastern and western civilisation, and the results of an influx of western ideas into the heart of China, a consummation against which she has striven so hard, is full of interest to all alike.” This article is available in Gale’s Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals.

Chinese Turkestan

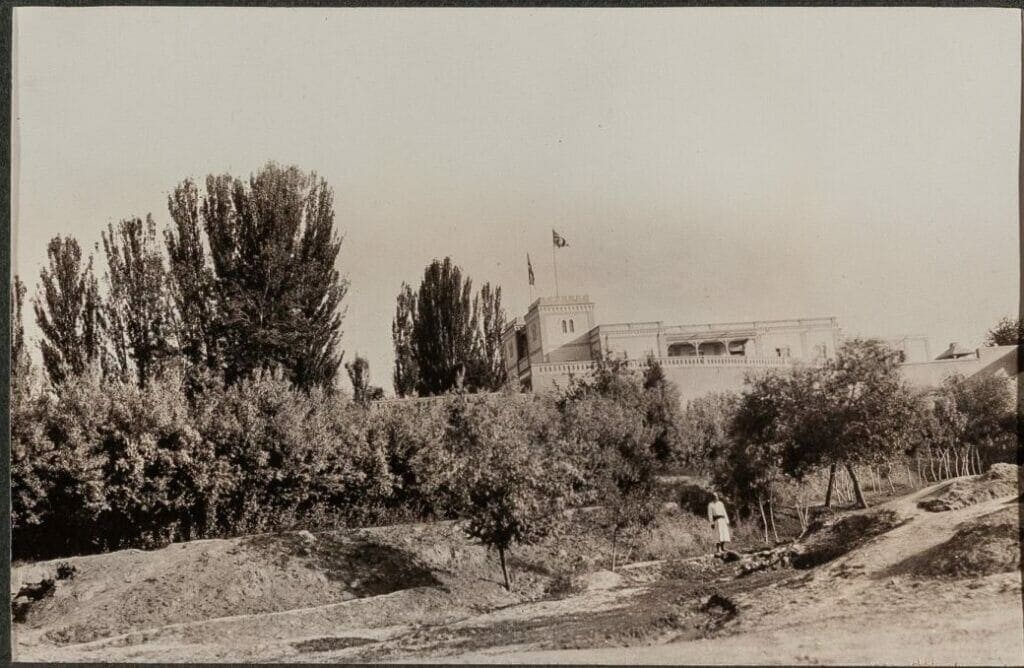

Xinjiang, which was referred to as “Chinese Turkestan” by Europeans in the nineteenth century, constituted an important component of the Silk Road. Percy Sykes, who was appointed the British consul-general in Chinese Turkestan in 1915, took numerous valuable photographs depicting the local life and customs there. These photographs can be found in Gale’s China and the Modern World: Political and Secret Department Records:

Chinese Turkestan lay at the heart of Asia, bordering British India in the south and Russia in the north. Given its strategic importance, Britain and Russia started vying with each other to increase their presence in this region in 1830, and their rivalry lasted throughout the nineteenth century. This is the so-called Great Game.

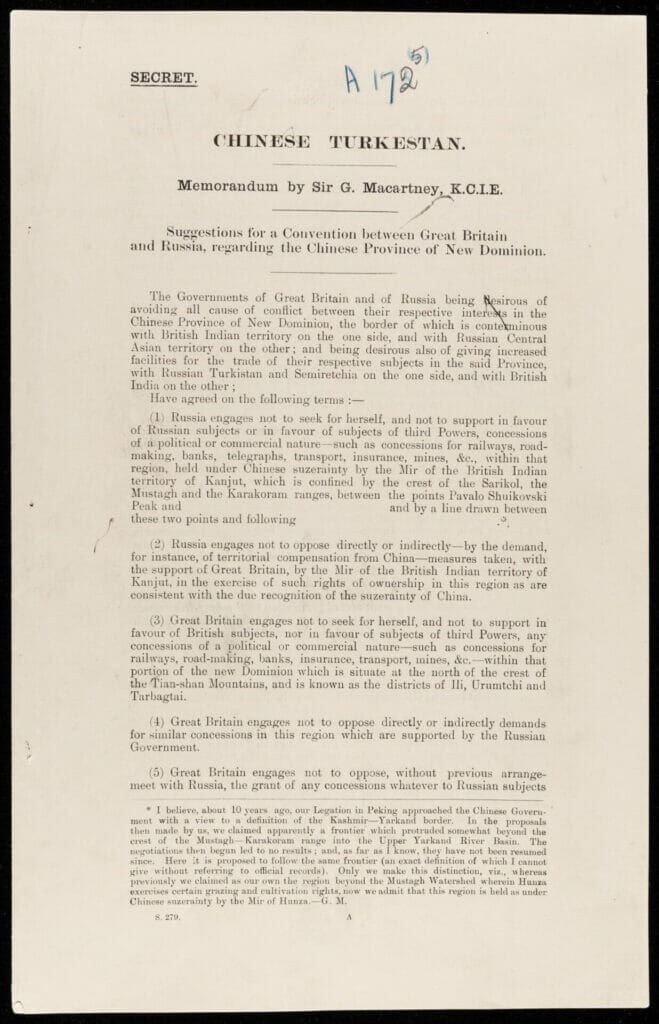

In 1890, George Halliday Macartney (1867–1945) arrived in Xinjiang as the interpreter for Sir Francis Edward Younghusband; between 1911 and 1918, he served as the British consul-general in Kashgar, providing the British government with a wealth of information on local situations. (You can read more about George Macartney and the Great Game here.) His intelligence reports are also included in the Political and Secret Department Records:

The 1792-94 Macartney Mission

Another important channel of international trade is the Maritime Silk Road, a sea route connecting China’s eastern shore to East Africa and Europe through the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea. Starting from the first century BC, it allowed merchants to ship luxury goods from China to Europe, including spices, tea, and precious gems and stones.

In 1792, King George III, then king of Great Britain and Ireland, dispatched an eighty-four-man mission headed by George Macartney to China, in an attempt to open trade and diplomatic relations with the Qing Empire. They sailed from Portsmouth, travelled along the Maritime Silk Road, and eventually arrived at the Chinese Emperor’s summer resort at Jehol (today’s Chengde City, Hebei Province).

Although it failed to achieve its desired results, the 1792-94 Macartney Mission was the first British diplomatic mission to China and was a significant episode in the relations between China and the United Kingdom. The Charles Wason Collection at Cornell University Library contains a large number of original letters, books, sketches, and journals written by members of the Macartney Mission. In 2018, Gale digitised this collection and released The Earl George Macartney Collection as a module within Archives Unbound. Those primary sources provide a spellbinding account of George Macartney’s trip.

Interestingly, George Macartney (1737–1806) was a member of the same family as George Halliday Macartney (1867–1945).

The Chinese Maritime Customs Service

The ancient Silk Road had been indispensable to the expansion of international trade for thousands of years since the Han Dynasty of China opened trade. However, it came to a halt in 1453 when the Ottoman Empire closed off trade with the West. The trade between China and the West did not resume on a large scale till the 1840s when China’s Qing Dynasty was defeated in the first Opium War with Britain and was forced to open five coastal cities for trade.

In the subsequent years until the mid-twentieth century, the Chinese Maritime Customs Service played a pivotal role in sustaining China’s foreign trade. Established in 1859, the Service produced a large number of archival materials, including Inspector General’s Circulars, London Office files, and Semi-Official Correspondence, furnishing a set of priceless collections for studying how the institution shaped China’s trade and even diplomatic relationship with the world during the period covered. These primary source materials form the core of Gale’s Records of the Maritime Customs Service of China, 1854–1949, a module in the China and the Modern World series.

Cultural and Religious Exchanges

Monks, missionaries, artists, and artisans also travelled along the ancient Silk Road, leading to East–West religious and cultural exchanges. Both Buddhism and Christianity have influenced China at different historical points. Hudson Taylor, founder of the China Inland Mission (CIM), is widely acknowledged to be one of the most important Protestant missionaries to China in the nineteenth century.

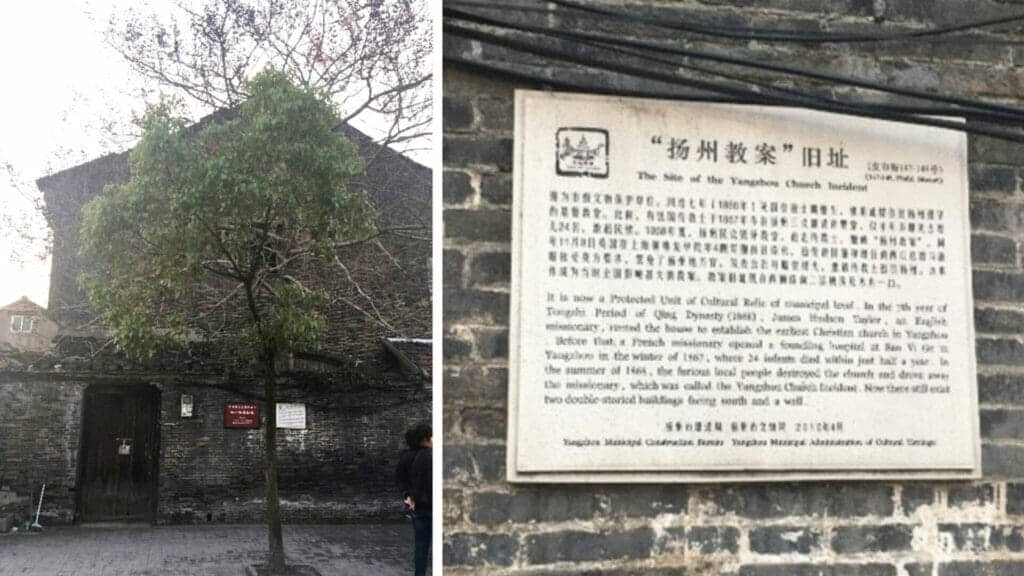

On August 22, 1868, an anti-missionary riot broke out in Yangchow (or Yangzhou in today’s pinyin romanization system). An angry group of Chinese attacked members of the CIM, including Taylor’s family, and assaulted the CIM house. Maria, wife of Hudson Taylor, had to jump from the burning house to escape whilst six months pregnant with their fourth child. Today, the original site of the CIM house has been preserved as a local historical and cultural site, becoming a tourist attraction in Yangzhou City.

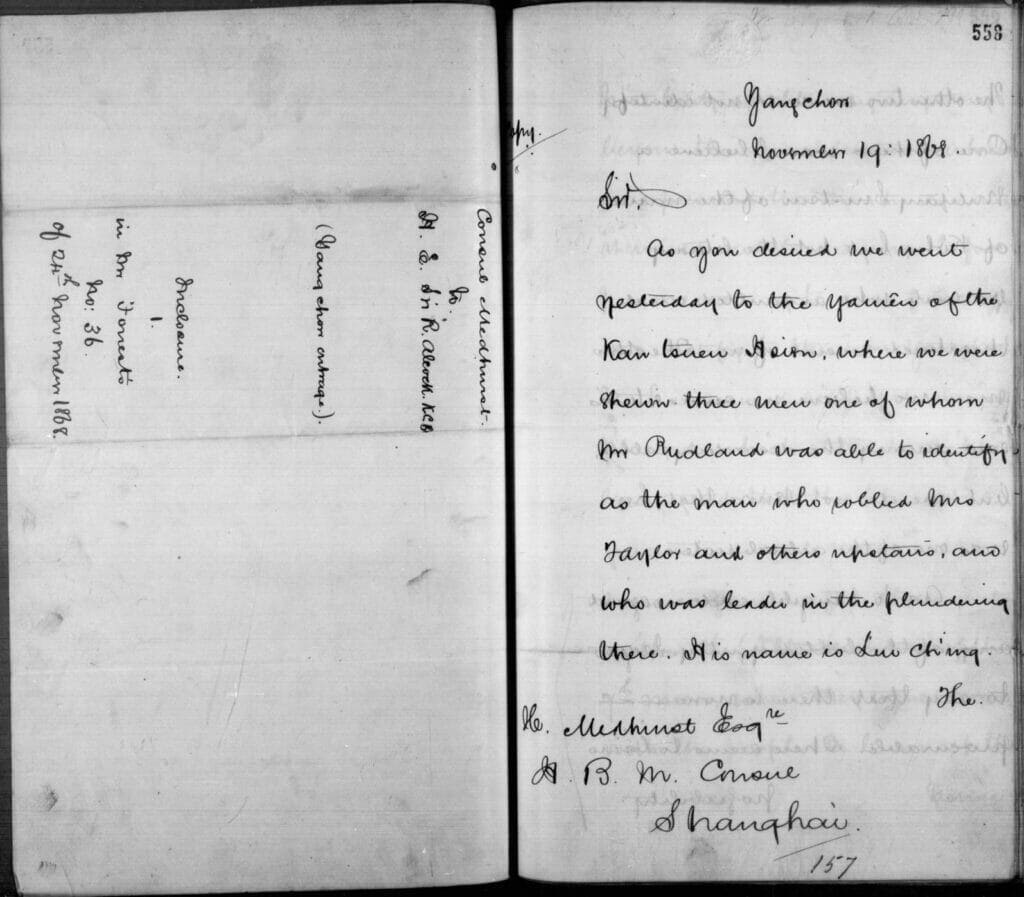

In the British Foreign Office archival collection FO 17, which is included in China and the Modern World, there are letters between Hudson Taylor and the British consul-general in Shanghai, describing the development of CIM and what happened during the riot. Those historical materials offer a fresh perspective on the study of modern Chinese history.

Modern Impacts of Missionary Activity

In the spring of 2020, COVID-19 ravaged the Chinese city of Wuhan. In February of that year, a team of medical workers from four top hospitals in China (that is, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Xiangya Hospital, Cheeloo Hospital, and West China Hospital of Sichuan University) arrived in Wuhan to fight the epidemic. These four hospitals, which represent the highest level of medical care in China, all have deep ties with missionaries.

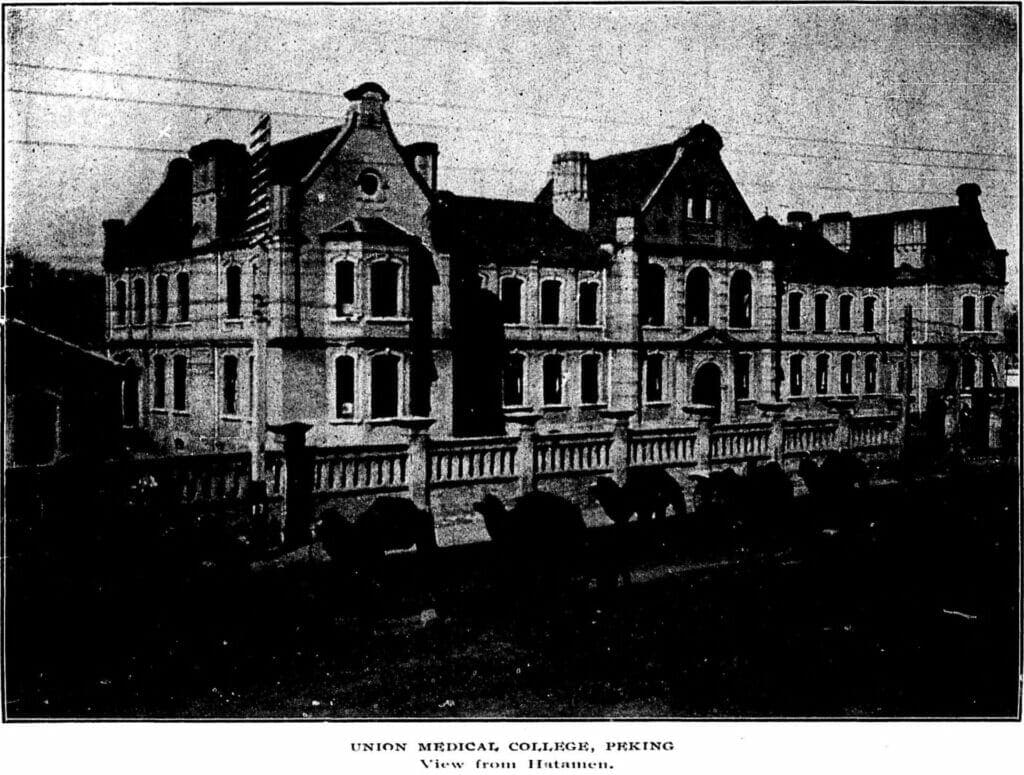

In 1906, the London Missionary Society and five other British and American churches jointly founded the Union Medical College in Beijing, hoping to improve China’s poor medical condition at that time. Later, the Rockefeller Foundation decided to establish the Peking Union Medical College on the basis of the Union Medical College to promote Western science and education. On September 24, 1917, the Rockefeller Foundation held the groundbreaking ceremony for the medical college in Beijing. A news report of this event was documented in Chinese Recorder, an English journal published by Western missionaries in China.

Chinese Recorder, together with sixteen other English-language periodicals published in or about China from 1817 until the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, can be found in Gale’s China and the Modern World: Missionary, Sinology and Literary Periodicals, 1817-1949.

“Union Medical College, Peking.” The Chinese Recorder, vol. 41, no. 2, Feb. 1910, p. 191. China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/NFGZZW964901649/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=57a59c28

Gale eBooks on the Silk Road

Books on the history of the countries along the ancient Silk Road, such as those in Central Asia, provide important secondary sources for understanding and researching these countries and their ties with the Silk Road yesterday and today. The Gale eBooks platform hosts several books on the history of Central Asia, including Central Asia: A New History from the Imperial Conquests to the Present written by Adeeb Khalid, a professor of history at Carleton College. Readers can gain insights into the vicissitudes of Central Asia from the mid-eighteenth century to the present, including the influence of the Qing Empire and Russia on the region and its involvement in global trade. Another good reference book relating to history of modern China and Silk Road is the four-volume Encyclopedia of Modern China edited by David Pong.

Right: Encyclopedia of Modern China edited by David Pong.

Connectivity is the core of the ancient Silk Road and the heart of today’s BRI. In 2020, Gale Asia published Global Leaders on the Belt and Road Initiative, a collection of interviews conducted by the author, Sun Chao, with 36 leaders from various partner countries and international organisations. It showcases how this initiative has deepened connectivity between China and the world and promoted economic development in countries along the route. This book is also available on the Gale eBooks platform.

If you enjoyed reading about the resources Gale offers to study and research the Belt and Road Initiative, you may like:

- George Macartney, Kashgar and the Great Game

- Researching the Impact of the New Silk Road on Kazakhstan

- Early Twentieth-Century Explorers in Inland Asia

- Ngiam Tong-Fatt’s Essays Provide Great Insight into Mid-Twentieth Century Southeast Asia

- The Rise and Fall of Chinese Indentured Labour

- The Bowring Treaty and the Opening up of Thailand

Blog post cover image citation: China Railway sketch Map. From Domestic Various. January-February, 1865. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/438.The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CAHZAY112181655/CFER?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=d49c0b4a&pg=331