│By Emery Pan, Associate Development Editor│

In 2001, the Korean television series Empress Myeongseong became a massive hit in many Asian countries. Empress Myeongseong, also known as Queen Min [闵妃], was the wife of Gojong [高宗], the ruler of Korea from 1864 to 1907. Her real life, explored below using primary sources from the Gale archive China and the Modern World, was actually far more complicated and bloody than it appeared in the historical drama.

Early Life

In 1851, Min was born into a noble household that had come down in the world. Sixteen years later, she married the 15-year-old Gojong under the arrangement of the Korean King Heungseon Daewongun [兴宣大院君] (1820–1898), or Tai-won Kun—a decision that he regretted for the rest of his life. In the eyes of Tai-won Kun, Min was the perfect wife for Gojong: someone from an aristocratic yet powerless family who could easily be manipulated. However, after reaching adulthood, the seemingly submissive queen started to show her ambition and became the de facto ruler of Korea with her extraordinary political skills and intelligence.

The Rise of Japan

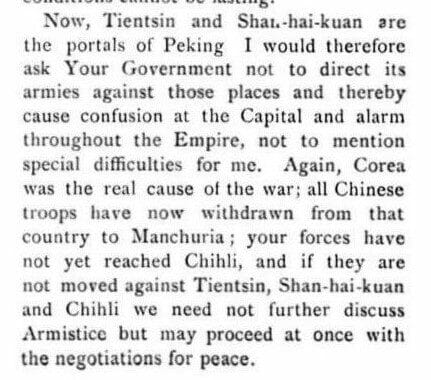

The Meiji Restoration [明治维新] initiated in Japan in 1868 transformed the country into a modern military power. With its increased military might, Japan was keen to expand its influence over Korea—a tributary state of the Qing Dynasty at that time—and further assert its military power overseas. Such an ambition toward Korea exacerbated its conflict with China and led to the outbreak of the First Sino–Japanese War in July 1894. As Viceroy Li Hongzhang [李鸿章] commented during his peace negotiations with then Japanese Prime Minister Itō Hirobum [伊藤博文], “Corea was the real cause of the war [the First Sino–Japanese War]; all Chinese troops have now withdrawn from that country to Manchuria . . . .”

Sir N. O’Conor. Volume 7. Diplomatic. Despatches. 312-362. August 8-September 23, 1895. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/1238. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HJGITS071740721/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=15d193ec&pg=49

1895, a Year of Significance

1895 was a truly eventful year in the history of Asia. In April, the First Sino–Japanese War was concluded by the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki [马关条约], and the first article of the treaty provided for the independence and autonomy of Korea, thus ending Korea’s tributary relationship with the Qing Dynasty. However, the question is whether this article could guarantee Korea’s true independence and autonomy, or was simply a pretext for Japan to tighten its grip on the country.

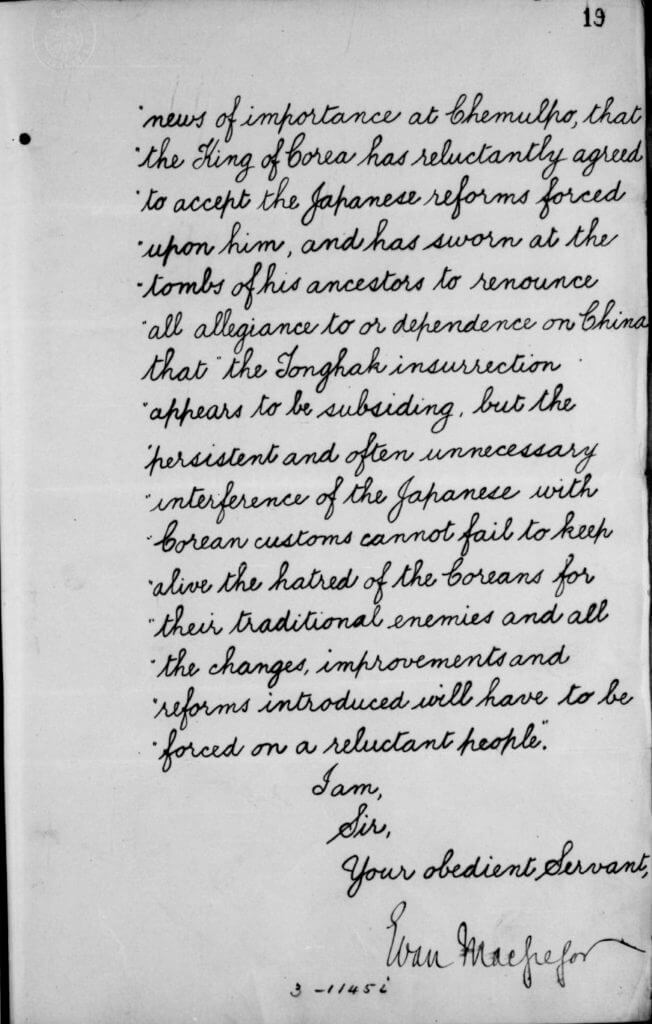

Meanwhile, Japan wanted to instigate a series of reforms in Korea; however, Gojong and Queen Min seemed reluctant to cooperate, as shown in a letter to the British Foreign Office from then Commander-in-Chief, China Station in March 1895:

“The King of Corea has reluctantly agreed to accept that Japanese reforms forced upon him, and has sworn at the tombs of his ancestors to renounce all allegiance to or dependence on China… the persistent and often unnecessary interference of the Japanese with Corean customs cannot fail to keep alive the hatred of the Coreans for their traditional enemies and all the changes, improvements and reforms introduced will have to be forced on a reluctant people.”

See source

Various. Volume 2. Diplomatic. March-May 7, 1895. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/1252. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HOHQCH607044715/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=725c9473&pg=24

Similarly, in May 1895, Sir Ernest Satow, then plenipotentiary of the British government to Japan, wrote in his diary that Japanese reforms were not accepted by the Korean government, and that although Gojong was anxious to launch reforms, he feared that the Korean government would be weakened by Japanese interference.1 This can be found in Volume 5 of Diaries and Travel Journals of Ernest Satow published by Gale.

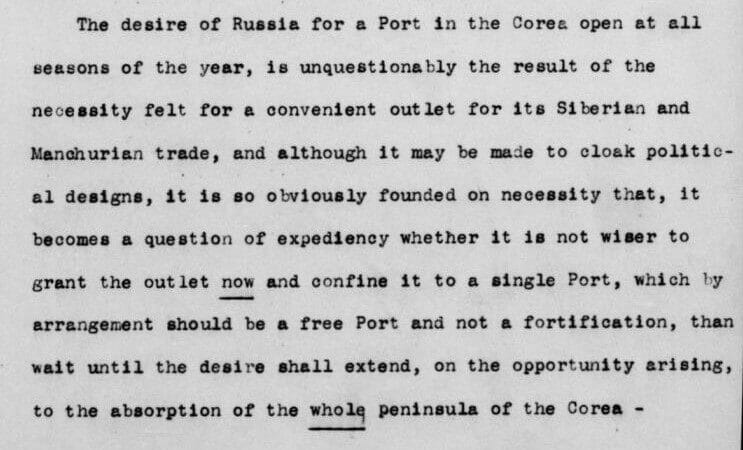

Japan was not the only country that coveted the land of Korea; Russia, too, yearned for the possession of the country due to its geographic significance. A letter to the Earls of Rosebery and Kimberley illuminated the reason: The Russian port Vladivostok [海参崴] was blocked with ice during winter, which paralyzed its trade and railroad extension through Siberia to the Japan Sea. Therefore, Russia needed a port in Korea, which would be “open at all seasons of the year . . . as an outlet for its Siberian and Manchurian trade.”

Various. Volume 2. Diplomatic. March-May 7, 1895. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/1252. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HOHQCH607044715/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=725c9473&pg=89

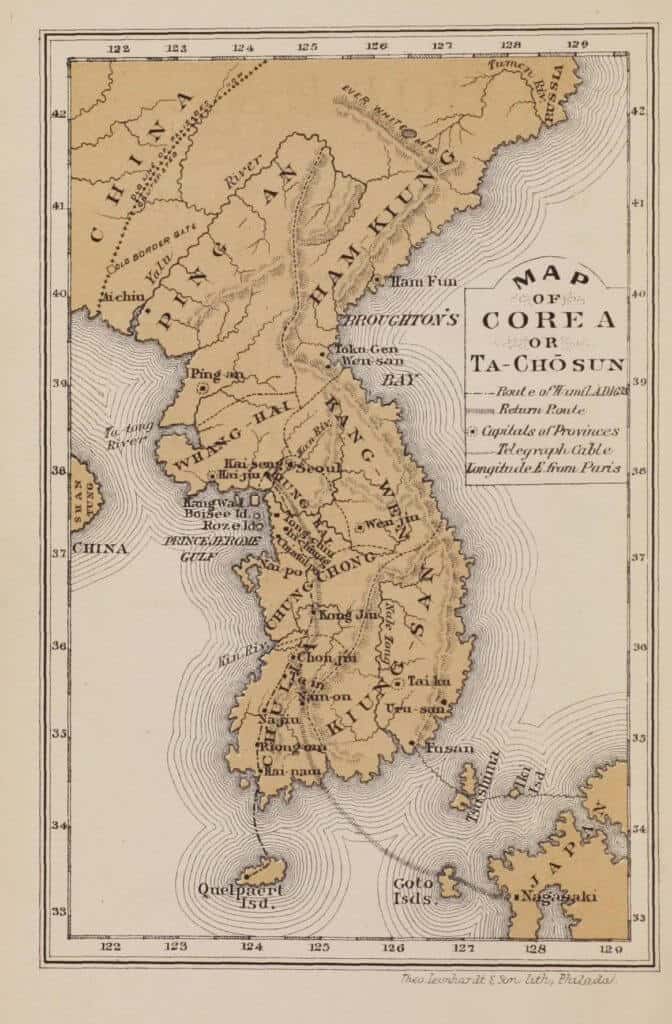

Griffis, William Elliot, and Hendrik Hamel. Corea, without and Within: Chapters on Corean History, Manners and Religion: With Hendrick Hamel’s Narrative of Captivity and Travels in Corea, …, [c1885]. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CYHDBI319155625/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=22a1506f&pg=217

In order to counter Japan’s influence on her country, Queen Min advocated a pro-Russia policy and sought Russia’s protection. Therefore, the Japanese government saw Gojong and Queen Min as their obstacles in their plan to subjugate Korea, foreshadowing her imminent death.

The Eulmi Incident: Queen Min’s murder

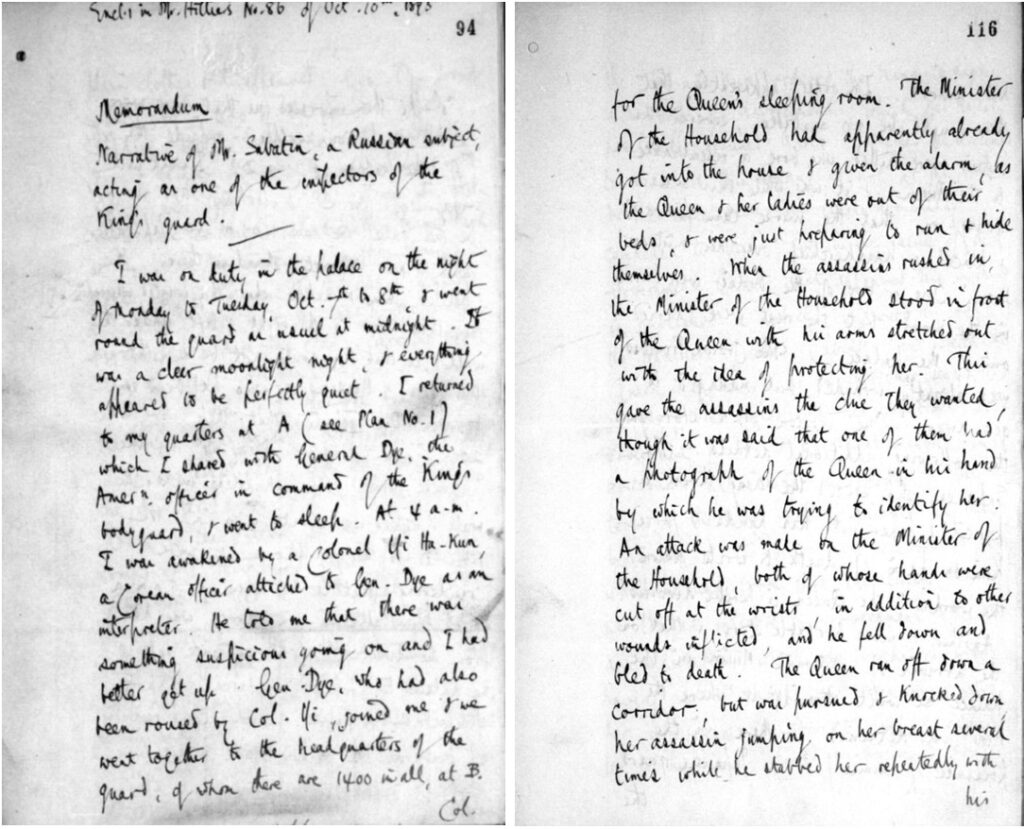

The dawn of October 8, 1895 saw the end of Queen Min’s life. The 44-year-old queen was assassinated viciously, an event known as the Eulmi Incident [乙未事变]. Afanasii Ivanovich Seredin-Sabatin, a Russian architect serving as an aide to the American General William McEntyre Dye in Seoul, gave an eyewitness account of the murder.

At around 4 a.m., Sabatin and General Dye were woken up by strange and loud noises from the inner court of the Gyeongbokgung palace [景阳宫] and went there to figure out what was happening—a group of Japanese soldiers had invaded the palace, searching for the queen. It was a truly brutal scene: the Japanese soldiers were “dragging women [Korean ladies in the palace] by the hair of the head, hurling them off the veranda, and kicking them as they fell.”

A couple of hours later, Sabatin sensed that he was no longer safe to stay in the palace and needed to flee. On his way out, he was seized by a Korean official and a group of Japanese soldiers, who asked him where the queen was while dragging him across the courtyard. As Sabatin recounted, “I protested that I did not know, and they were proceeding to handle me pretty roughly when the Japanese [individual] again came up. I appealed to him for protection, and when he had heard what the others had to say, he also asked me in English where the Queen was. I repeated that I did not know and asked for an escort to take me out of the palace.” Eventually, Sabatin was released and managed to escape.

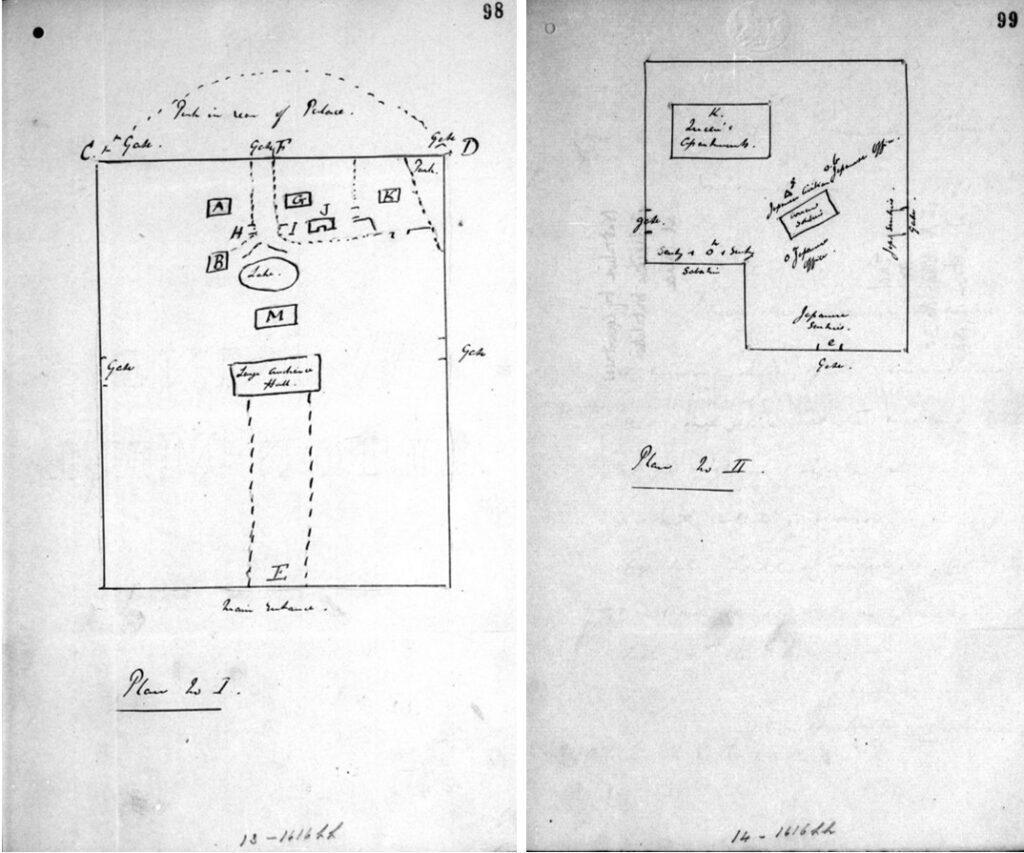

Sabatin also drew two maps of the palace and indicated his route of escape. These two maps, coupled with his testimony, were enclosed in a letter from then British Consul in Seoul to Sir Nicholas Roderick O’Conor, then British Minister in Beijing. The letter can be found in Gale’s China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part II, 1865–1905.

Left: Consul General at Soul; Hillier. Volume 2. Diplomatic. Drafts and Despatches. 23-48. July-December, 1895. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/1248. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HLPGKT408767194/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-FER&xid=c7c20bdc&pg=96

Right: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HLPGKT408767194/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-FER&xid=c7c20bdc&pg=118

Consul General at Soul; Hillier. Volume 2. Diplomatic. Drafts and Despatches. 23-48. July-December, 1895. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/1248. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HLPGKT408767194/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-FER&xid=c7c20bdc&pg=100

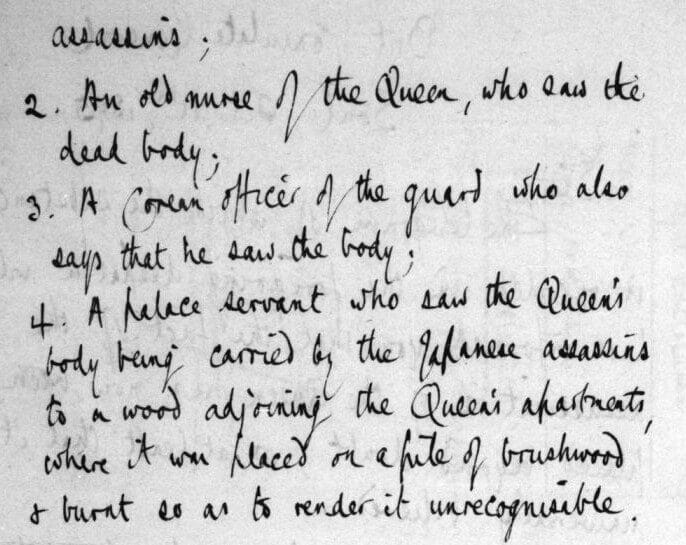

According to another letter from then British Consul General in Seoul to Sir N. R. O’Conor dated October 11, 1895, the murder of the queen was also witnessed by others, including “one of the ladies of the palace who says she saw the Queen cut down by Japanese assassins; an old nurse of the Queen, who saw the dead body; a Corean officer of the guard who also says that he saw the body; and a palace servant who saw the Queen’s body being carried by the Japanese assassins to a wood adjoining the Queen’s apartments, where it was placed on a pile of brushwood and burnt so as to render it unrecognizable.”

Consul General at Soul; Hillier. Volume 2. Diplomatic. Drafts and Despatches. 23-48. July-December, 1895. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/1248. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HLPGKT408767194/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-FER&xid=c7c20bdc&pg=118

Ernest Satow also mentioned this incident in his diary on October 14, 1895: “It was in his presence that the Queen was killed, either in his room or hers. It is said her head was cut off, wch. looks like a Japse. performance. No doubt Japse. were mixed up at it. Genl. Miura was at the Palace [景福宮] 5 min. later in his uniform!”2

Abundant evidence showed that the assassination was commissioned by Miura Gorō [三浦梧楼], then Japanese Minister to Korea, in an attempt to avoid losing Korea to other powers. Yet, aside from Miura Gorō, Queen Min’s father-in-law, Tai-won Kun, was also involved in orchestrating the assassination.

The involvement of Queen Min’s father-in-law, Tai-won Kun

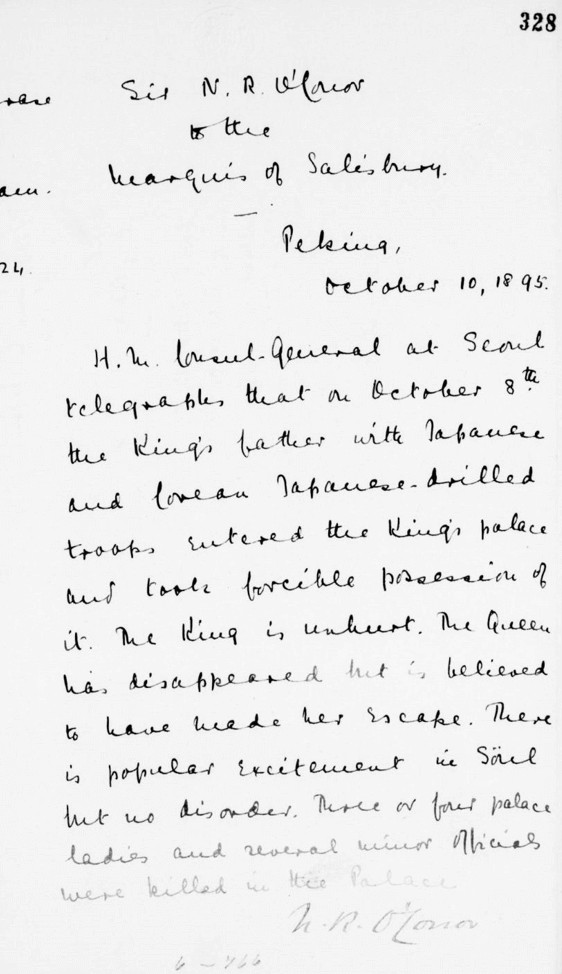

Back in 1882, before the outbreak of the First Sino–Japanese War in 1894, Tai-won Kun had been removed from power and kidnapped to China. Three years later, he was released from prison and returned to Korea, but by that time he had lost all his power to Queen Min. Additionally, unlike Queen Min, Tai-won Kun regarded Japan as a more reliable alliance and thus championed a pro-Japan policy. His growing resentment and political position eventually prompted him to ally with the Japanese government to murder his daughter-in-law. Soon after the death of the queen, he forcefully occupied the royal court. In his telegram to Lord Salisbury dated October 10, 1895, N.R. O’Conor reported that “the King’s father with Japanese and Corean Japanese-drilled troops entered the King’s palace and took forcible procession of it.”

Sir N. O’Conor, (Mr O’Conor), Mr Beauclerk. Diplomatic. Despatches. Telegrams and Paraphrases. 1895. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/1243. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IZXEWS513861104/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=05aa2865&pg=331

On November 24, 1895, Satow was told by Shigenobu Ōkuma [大隈重信], then Japanese Foreign Minister, that “the murder of the Queen was contrived by the Taiwön kun with the aid perh. of a few Japse. sōshi, and that the result had been to put all the foreigners in Corea agst. Japan.”3

Aftermath

After the death of Queen Min, Gojong and the crown prince fled from Gyeongbokgung palace to the Russian legation in Jeongdong [贞洞], Seoul—this move also showed the couple’s favouritism toward Russia. Her death also caused a chain of events, including the Russo-Japanese War from 1904 to 1905, a subject that is worth further study and research.

If you enjoyed reading about some of the fascinating content to be found in Gale’s China and the Modern World archive series, and other sources providing insight into Chinese history, try:

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century, Part II

- One Treaty, a Diplomat, and Three Countries – The Treaty of Shimonoseki

If you enjoyed reading about the historical background to the television series Empress Myeongseong, and historical crime, you might like:

- ‘A Genteel Murderess’ – Christiana Edmunds and the Chocolate Box Poisoning

- ‘The compartment was much bespattered with blood’: the Brighton Railway Murder

- The Whitechapel Murders: exploring Jack the Ripper’s victims in the Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture archive

- Are We Obsessed with Serial Killers?

Blog post cover image citation: Photo of King Gojong and Empress Myeongseong. Griffis, William Elliot, and Hendrik Hamel. Corea, without and Within: Chapters on Corean History, Manners and Religion: With Hendrick Hamel’s Narrative of Captivity and Travels in Corea, … [c1885]. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CYHDBI319155625/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=22a1506f&pg=217