│By Ayanda Netshisaulu, Gale Ambassador at the University of Johannesburg|

Let me set the scene. Right at the beginning of my postgraduate career, starry eyed and interested in gender history, I was offered the opportunity to join a group of students from the University of Johannesburg and Western Sydney University for a two-week programme in the Kruger National Park in north-eastern South Africa. The programme mostly consisted of Zoology students who understood the importance of land gradients and wild animal feeding patterns. As a Humanities student I felt a bit out of place but I wasn’t particularly bothered considering I was enjoying the safari and learning about rhino’s territorial marking patterns!

It was during this trip, however, that I learned that historical narratives can be extracted from anything. We had been discussing land gradients – which to this day I don’t completely understand – when my History professor asked me: “gradients and the science aside, Ayanda what did you get from what was just said now?” What did I get? I was still trying to get my Humanities brain to catch up to the science of it all! How could I “get” anything? He then went on to explain how, for a historian, there is a story in everything. A historian would be asking themselves questions about past land use, about past peoples and about how they would have navigated this land. How did societies of the past know, for example, to burn the grass to allow for the fresh regrowth that would attract game? Whilst initially I had never felt so out of place, it was during this trip that I fell in love with the historical narratives of the environmental past.

Field trips and deep thoughts

Later that week, we walked through fields still mostly untouched by present human innovation, on land with many stories to tell. As we walked through the wooded fields with a guide constantly warning us about the possibility of a wild animal attack, stories were exchanged. In a time long ago, people lived within these fields, arguably in harmony with the same wild animals we were being warned about (although admittedly that romanticises the narrative of pre-colonial African life). Romanticism aside, people of the past related to their surroundings very differently to how we do today.

As we were walking along the riverbank, I was picturing young women collecting water, children splashing through the water on the warm summer days, older women preparing fires and men stalking their prey, using the land so differently to how we use today. I could also picture shamans and traditional healers walking through the more dense undergrowth, collecting plants and herbs that they believed were essential to their divination practices. And it is the latter which I would soon be researching!

Amboseli National Park, Kenya. Image by Sergey Pesterev on Unsplash.com https://unsplash.com/photos/wdMWMHXUpsc

As I looked at all the flora and fauna – with most of the trees now trampled by the movement of large animals – I thought of all that green and brown which people were immersed in. How did they conceptualise all that was around them? As I looked around, I wondered what secrets they thought the plants held. It is in the midst of such thoughts that I came to know I wanted to be an Environmental History researcher.

What is Environmental History?

How lucky was it that, with the start of academic year, an Environmental History semester-length course was on offer at my university? Through this course, I learned that there are many branches of Environmental History. But what is Environmental History, you may ask? Environmental History is a collision of different disciplines – Ecology, Geography and, in my case, Botany – that are brought together to investigate the changes and even the politics of environmental management.

Many researchers have examined how nature was in the past, and how it has changed over the years as a result of colonialism and industrialisation. Numerous researchers in the global South have focused on the land use of the poor – those who have no choice but to live off the land, and in doing so they are investigating the politics of the environment. Unlike these researchers, I chose to investigate plant magic and its importance in modern day practices.

Having always had in interest in what others would see as the “mystical,” it seemed only right for me to research how and why societies of the past used plants in divination. To my chagrin, most of the existing plant-use research investigates the medicinal uses of plants; only writing, for example, about how plants were used pre-colonially to treat injuries such as cuts. Though there is also coverage of how plants were used to treat mental illness or psychological disturbances.

How Gale helped me with my research

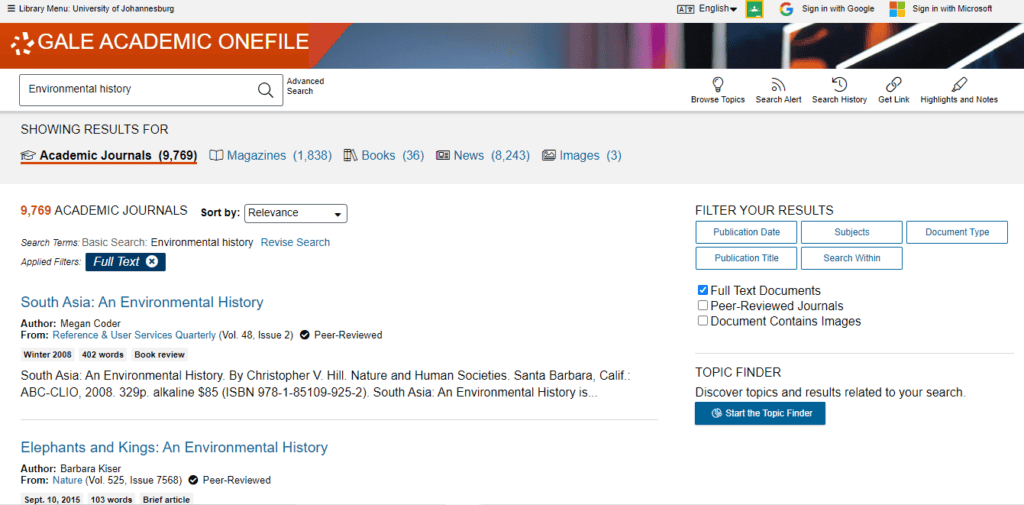

I was pleased to discover that the Gale database offers introductory essays into the niche content of Environmental History. As a postgraduate I have come to appreciate the secondary sources which are, as my supervisors says, the building blocks of historical research. Gale Academic OneFile offers an extensive collection of secondary sources – great for building targeted knowledge on the arguments and nuances surrounding Environmental History.

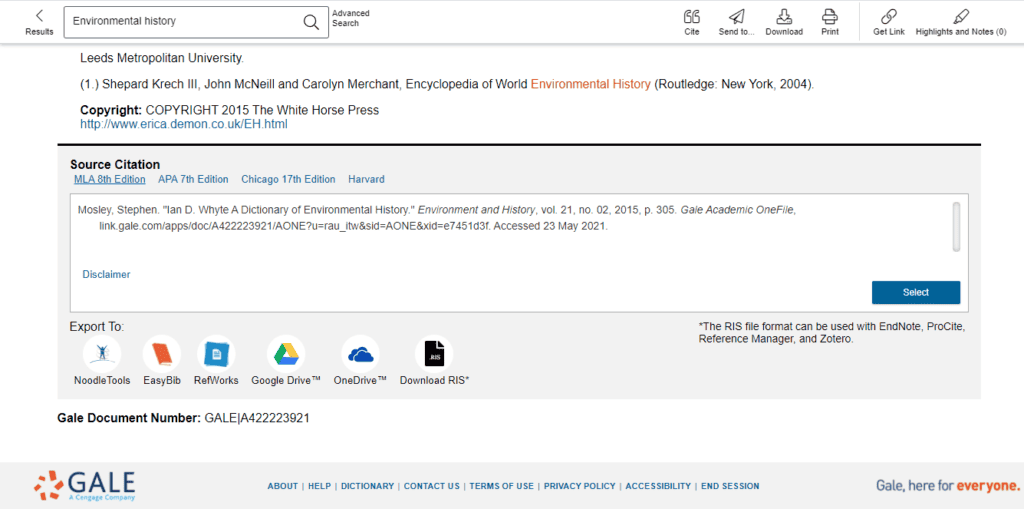

Gale’s resources provide the user – whether a novice undergraduate or a seasoned researcher – with access to summaries on books and journal articles that build a contextual basis of Environmental History. For example, the book review of Ian Whyte’s A Dictionary of Environmental History informs the researcher firstly that there is such an introductory book in existence (!) helping the user to find the best source material and, perhaps more importantly, provides the reader with a summary of the book. I have found such introductory books inform most of my research methodology, often leading me towards the topics within Environmental History that I subsequently find of most interest. Indeed, I find the citations in such books often act as a study guide and reference point.

Ethnobotony

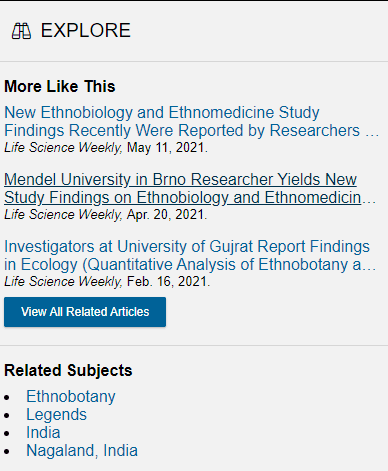

Ethnobotony has not been extensively researched, and has proved very difficult to research, despite being a topic I find intriguing. I have often relied on the materials mentioned in the articles that I am already reading. But no two researchers use data the same way, right? Right. Which is why it is important to be able to find more articles myself, rather than relying on what’s mentioned in the articles I am reading. And Gale has made that far easier! Through the “More Like This” feature, Gale provides a list of articles similar to the one I am viewing (much like Netflix or YouTube recommend videos based on what I have previously watched), thus providing me with many more potential research paths.

Environmental History, especially ethnobotanical research, has proved quite difficult to tackle, but Gale Academic OneFile has proved extremely helpful, providing me with secondary sources and international case studies from which to build my arguments in this fascinating, albeit niche, area of historical research.

If you enjoyed reading about Ayanda’s passion for Environmental History you may enjoy reading these posts by Amelie Bonney, a doctoral student in History of Science, Medicine and Technology at the University of Oxford:

- Explaining Volcanic Eruptions from the Late Eighteenth Century to the Modern Day

- Canaries in the Coal Mine

Or the following posts which explore aspects of the environment, science and history:

- The Myth of the Rhinoceros

- Understanding the Climax of HBO’s Mini-Series “Chernobyl”

- Indigenous populations: exploring early encounters, subjugation and protection

Blog post cover image citation: Gradina Botanica, Bucharest. Image by Eduard Militaru on Unsplash.com https://unsplash.com/photos/NgiE1A-lIyY