│By Lily Cratchley, Gale Ambassador at the University of Birmingham│

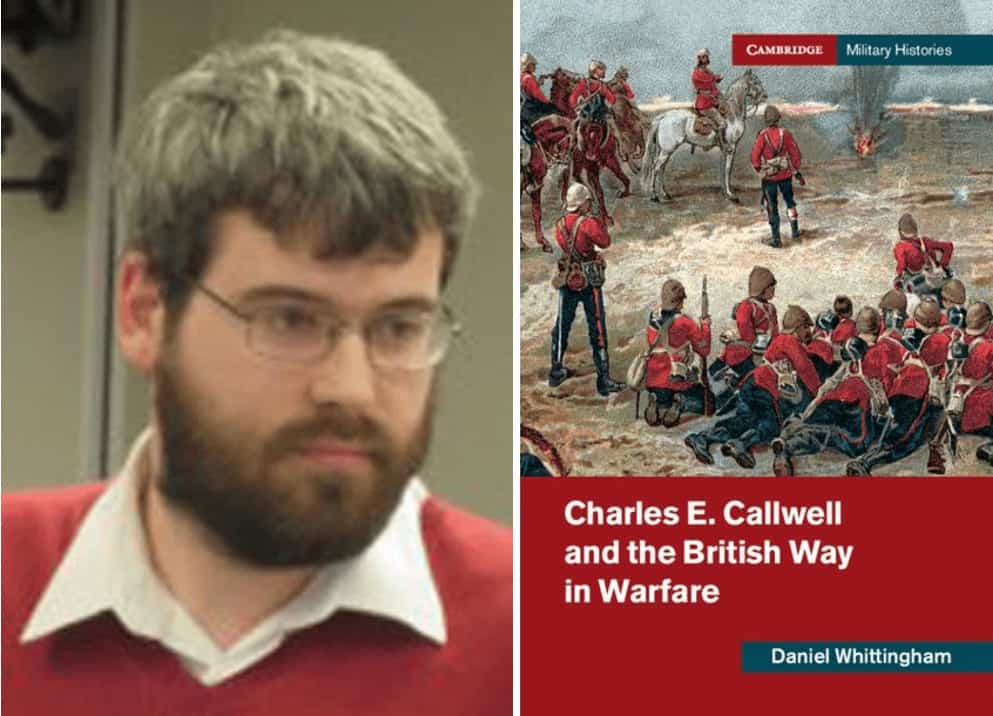

Through the medium of a Zoom interview, Dr Daniel Whittingham, History Lecturer at the University of Birmingham, talked me through how he found Gale Primary Sources integral to writing his book, Charles E. Callwell and the British Way in Warfare (Cambridge University Press, 2019), and then kindly offered his professional advice for students about finding, using and citing online archives, including the best ways to incorporate primary sources into an essay or dissertation.

Dr Daniel Whittingham lectures at the University of Birmingham, specialising in the History of Warfare and Conflict and convenes a module for third-year students on the American Civil War.

Which Gale archives do you have experience using?

Dr Whittingham’s book, Charles E. Callwell and the British Way in Warfare, provides insight into Major-General Callwell’s writing during the period 1859-1928. It includes analysis of the newspaper articles Callwell wrote as well as his longer and more well-known texts, and thus he used material in Gale’s newspaper archives such as Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals, The Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive, Daily Mail Historical Archive and The Times Digital Archive. Whittingham explained how helpful he found Gale’s archives in achieving this in-depth analysis of Callwell’s writing.

Whittingham went on to praise these online databases, specifically their search functions, which allowed him to easily run searches with key names and other relevant material. Other features Whittingham found useful in his academic research was the ease of collating sources from a large quantity of material into a more manageable amount, and also the ease of printing them.

How do academics use primary sources in their teaching?

Whittingham emphasises how important primary sources are to his teaching at the university. For example, he runs a module on the American Civil War, his specialised subject, which has a teaching week dedicated to British responses to the events in America. Whittingham tells me how the use of British newspaper articles is vital during this week, and that he directs students to look at material from archives such as British Library Newspapers.

Whittingham also mentions that analysing primary sources is a crucial part of the assessment of History students. He explains that part of his module’s final assignment is graded on a “Source Commentary” and how one hour every week is dedicated to finding and evaluating primary source material. Whittingham also makes clear how fundamental being able to properly use primary sources is to final year students who are undertaking dissertations, suggesting this is “a window into what being a professional historian is like.”

“RECENT BRITISH WARS.” Morning Post, 4 June 1887, p. 3. British Library Newspapers, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/R3214829236/GDCS?u=bham_uk&sid=GDCS&xid=bfce592a

What advice would you give to students who are struggling to cite online research sources?

I know from my own experience, and that of my peers, that citing online sources can seem like a minefield for stressed students, under pressure to submit their essay before a rapidly incoming deadline. Whittingham agrees, saying he is frequently asked this question by his students. However, citing online primary sources is, he emphasises, not that different from citing any online book or journal, explaining how online sources from newspapers should be cited like any other article. In addition, he states that materials found in archives such as Nineteenth Century UK Periodicals, should be cited as journal articles.

Whittingham also provided some insight into how and when students should link to websites. He warns that including lengthy URLs to individual primary sources is “not always necessary” in the final draft of an essay, and can often let the essay down in terms of neat and proper presentation. However, if your source is a website, rather than a specific article or journal, then linking to it is appropriate and students should remember to cite the URL and the date they accessed the website.

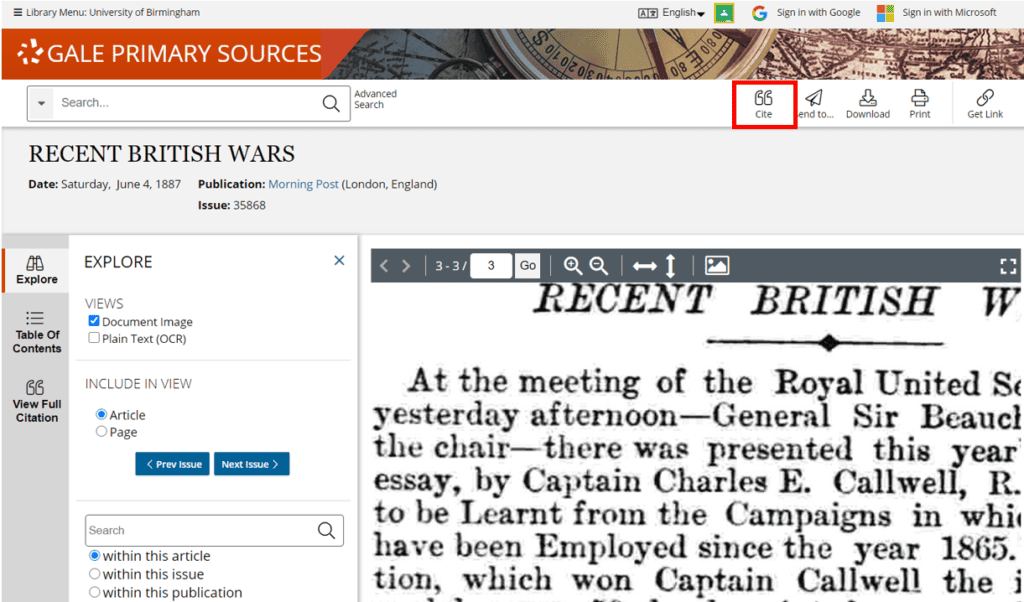

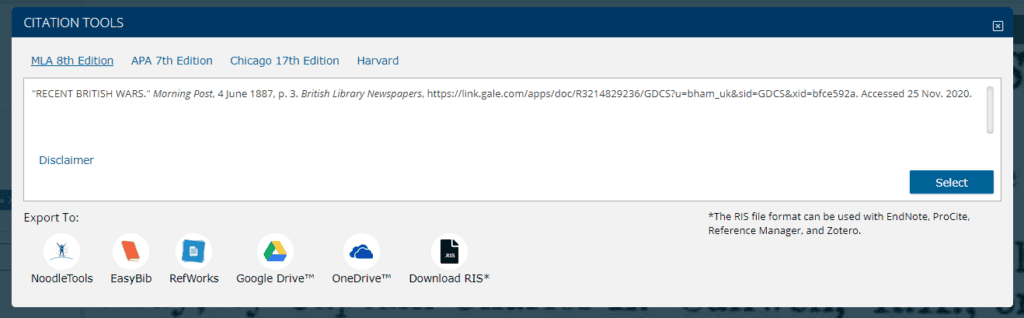

Usefully, Gale Primary Sources provides ready-made citations for all documents contained in the Gale archives, made available via the “Citation Tools” feature. This also provides citations in numerous formats, from MLA to Chicago and Harvard, and allows you to export the citations to tools such as RefWorks, EasyBib and NoodleTools. For the document above, the citation can be accessed as so:

I’ve found it can be useful to use the source URLs provided in Gale Primary Sources whilst compiling lists of sources I might like to use and when initially writing an essay, as they provide a direct link back to the source – very useful if you need to re-read or check a source! The “Get Link” tool can also generate a link to the exact page within a document – particularly useful if that document is a monograph of several hundred pages!

Do you have any tips for students conducting online research remotely this year?

Whittingham went on to share his advice for students who may be struggling to extract relevant primary source material from online databases. He stressed the importance of patience, in allowing yourself time to understand properly how individual archives are structured. He also highlighted the importance of thinking deeply about the particular key words and search terms you use – of searching for terms that were used to describe events at the time of the event, which is not always the same as the terminology we associate with it now. These are, after all, primary sources, so the author is often (though not always) part of the time period about which they were writing and would thus have used contemporary terminology.

Being systematic about online research is also a key bit of advice Whittingham shares with me. He advises students to make a record of every step they take and make careful notes, either online or handwritten, as they go, in order to best handle a large quantity of source material.

What do you look for when marking student essays?

For students wondering how best to evaluate primary source material in dissertations or essays, Whittingham offers some invaluable insight. Whether the source is a written extract, image, photograph or speech, the following checklist can be used. It provides five clear aspects for students to consider when analysing a source. These are:

- Author – An awareness of who authored, or produced, the source.

- Audience – Who the intended audience was.

- Context – The wider context of the source.

- Content – The specific content of the source.

- Implications – The implications of the source, aiming to ultimately link the source to a wider historical debate.

Dr Whittingham says he, like other lecturers, will be looking for consideration of these key points of perception when marking students’ work, so make sure you address them in your argument!

Whittingham finishes the interview by reiterating how fundamental correct use of primary sources in essays is to university students and academics alike. We also talked about how helpful the interdisciplinary nature of the archives within Gale Primary Sources is to students in a range of subject areas, including History, English Literature, Politics, International Relations, Economics and Finance – specifically archives such as The Economist Historical Archive and Financial Times Historical Archive.

If you’re looking for more useful research tips and tricks, check out these study tips to tackle tough academic works or one student’s tips for studying in lockdown. If you enjoyed reading this interview with an academic (and discovering how lecturers too are undertaking research with primary source archives!) check out ‘How a History Lecturer uses Gale Primary Sources to Research Spanish National Pride.‘

Blog post cover image citation: Image by Headway (@headwayio) on Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/photos/5QgIuuBxKwM