1843 saw some significant events in world history: Hong Kong was proclaimed a British Crown colony, the amusement park at the Tivoli Gardens opened in Copenhagen (currently the second oldest in the world!), and The Economist published its first issue. This August is the 175th anniversary of The Economist, so it seemed a good opportunity to look back at that first issue.

The Economist

Damiselas en apuros: voces femeninas del siglo XX

Por Paula Maher Martin, Gale Ambassador en la Universidad NUI Galway

“Lo que las mujeres son para las mujeres”, una sinfonía de pensamientos e impresiones, un lenguaje pulido delicadamente para reflejar el “cuerpo”, resonando con una “percepción” femenina de la realidad… En una crítica de A Room of One’s Own, de Virginia Woolf en el Times Literary Supplement (1929), Arthur Mc Dowall sintetiza en estos términos la experiencia femenina en la literatura, según sugiere Woolf.

“Damsels in distress”: lost female voices of the twentieth century

By Paula Maher Martin, Gale Ambassador at NUI Galway

“What women are to women”, a symphony of thoughts and impressions, language polished delicately to reflect the “body,” resounding with a feminine “grasp” of reality… In a 1929 Times Literary Supplement review of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, Arthur Mc Dowall synthesises in these terms the female experience in literature, as intimated by Woolf.

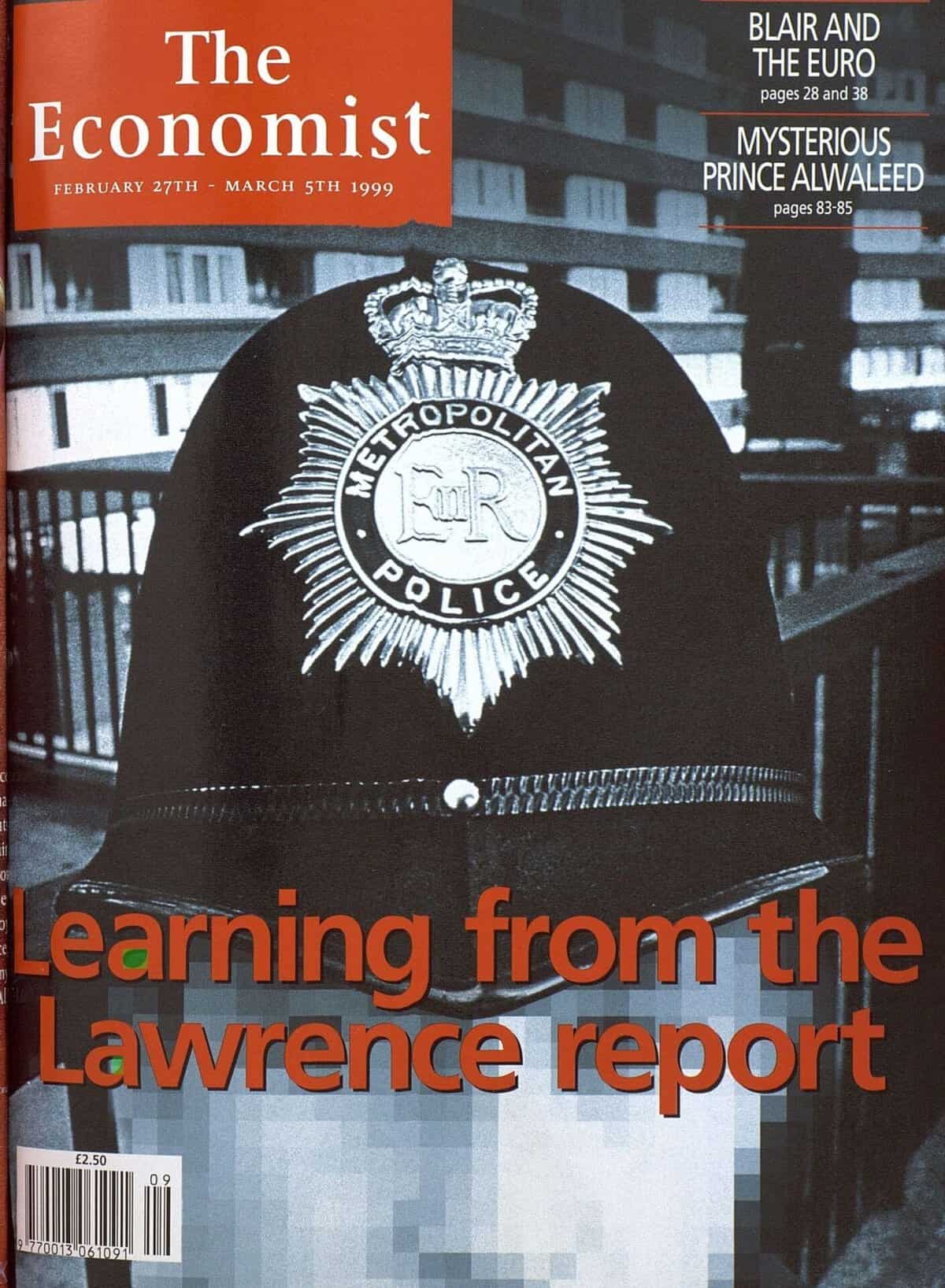

Twenty-Five Years Later: The Murder of Stephen Lawrence

By Rebecca Bowden, Associate Acquisitions Editor

‘The community was already in mourning… they were really frightened when their young ones go out, because they don’t know when the police be knocking the door.’

Interview with an anonymous source by Dr Gavin Bailey, Manchester Metropolitan University and Dr Ben Lee, Lancaster University, 2015, which will be featured in Gale’s new archive Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century archive, releasing in June 2018.

“Judge my work not me” Searching for misogyny in literary reviews

By Anna Sikora, Gale Ambassador at NUI Galway

In the recent movie To Walk Invisible (2016), a biopic depicting the lives of the famous Brontë sisters, Charlotte tells her sisters to publish their work under male pseudonyms. This, the oldest Brontë supposedly reasoned, was to prevent the publishers from judging the authors, and to invite them to judge the story instead. A certain degree of moral indignation prompted some of my students to take Charlotte’s statement as a cue to sweepingly proclaim that none of the Brontë sisters would have been published had they submitted as Anne, Emily and Charlotte. If this were true, said I (a woman), there would have been no literature by women in print until Ms Wolf entered the literary scene. Generalisations and hasty conclusions kill critical thinking, so let’s take a step back and read what was actually written about the early women writers publishing under their real names and literary aliases at the time their works hit the bookshop and library shelves.

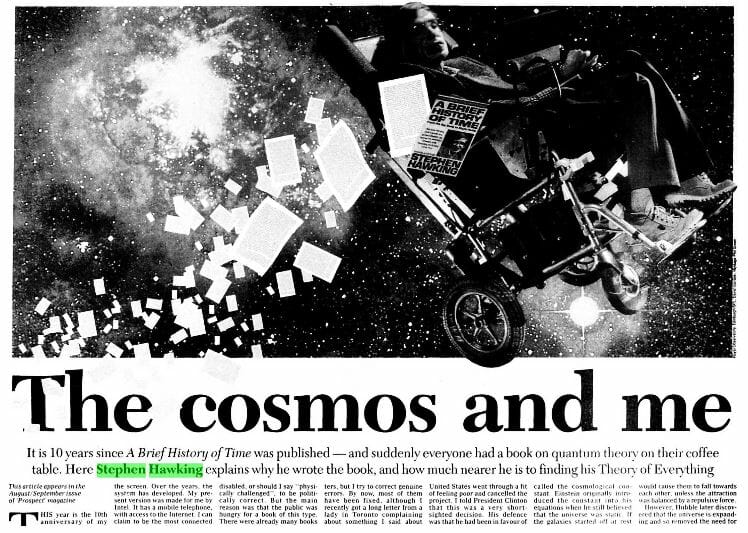

“This is all mind-boggling stuff”: The Reception of A Brief History of Time

On January 8th 2017, Professor Stephen Hawking celebrates his 75th birthday. Few scientists have such a strong place in the popular imagination, being the subject of numerous media from Hollywood films to documentaries to books, among many others. For 30 years he held the post of Lucasian Professor at Cambridge University, a chair held by no less than Sir Isaac Newton, filling some rather large shoes.