By Rebekka Väisänen, Gale Ambassador at the University of Helsinki

The Book Thief, by Markus Zusak, was one of the most captivating novels that I have had the pleasure of reading, so when the time came (last year) for me to finally write my BA thesis, I set to work brainstorming topics in which I could get away with re-reading and analyzing this novel in a seminar geared towards cognitive theory. The field I settled in was historical fiction. The Book Thief is set in the 1940s, in a small fictional town in Germany that is shaken by the rising power of Hitler and the conflict which later became known as the Second World War. The book opened my eyes to the horrors of war in a totally new way, and I started looking for more channels of entertainment-but-also-history through which to usefully procrastinate. I noticed that the Second World War has recently become a popular setting in mainstream media as well, with TV series based on ‘true stories’ emerging from a variety of viewpoints, including German (Hotel Adlon, Unsere Mutter Unsere Vater / Generation War, Babylon Berlin), British (Homefires), Irish and American (My Mother and Other Strangers).

But after consuming many of these embellished accounts of history, (and finishing my thesis), my curiosity was piqued, and I set out to find true, first-hand accounts of life during the war. And this is where Gale’s archives came in. With a few simple keywords – and limiting publication year to between 1940-1960 – the Gale Primary Sources platform presented me with hundreds of insights into ordinary life during the war. Mostly from small local newspapers found in the British Library Newspapers archive, the stories ranged from surprising events back home – like the British wife who hid an escaped German POW and left her husband when he found out – to the endearing pleas of young soldiers; whether it be asking around for a girl to marry before he is dispatched again, or requesting new pen pals because he was a ‘single and unattached’ POW bothered by the fact that his inmates were getting more letters than he was! As well as the joyful stories, such as when a soldier thought to be missing turns up fine, there are the short, sad news stories, not only of those fallen in battle, but of those who could not cope with the emotional and mental battle on the home front.

Every real-life snippet I read seemed worthy of a primetime show. But that’s the thing; these events weren’t just made up for entertainment. They actually happened. And I think being able to read newspapers from the past, having access to primary sources from any point in history, is really important, because otherwise we forget what was the reality. We forget the horrors of war were experienced by real people, and we forget the actions and mentalities upheld by societies that led up to war.

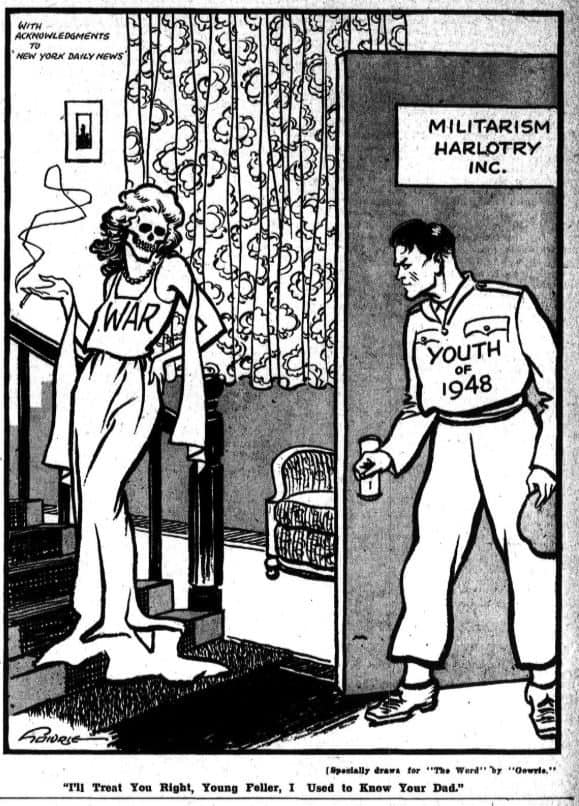

“I’ll treat you right, Young Feller, I used to know your Dad.”

from Alderton, R. “War on War.” Word, Sept. 1948, p. [133]. Nineteenth Century Collections Online. Accessed 9 Dec. 2018. http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/8XVAE4#.XA2Emib8hYI.link

What struck me personally was the postscript Allridge added three years later. Jane is already a young woman going off to study to be a teacher. He warns her of the tremendous influence she will have on her class, as ‘children are born – thank God! – without prejudice. It has to be carefully taught.’ He continues, ‘soon you will have charge of a class of six-year-olds. Don’t let them grow up afraid of people whose eyes are oddly made, and people whose skin is a different shade. It is a tremendous responsibility and a tremendous challenge. I know you will be equal to it.’ I’m also studying to be a teacher, and I took his advice to heart. We are in charge of the future, we have the power to shape it, and as teachers, we have the power to influence the future leaders of the world. But it is not only the responsibility of teachers. It is something we can all strive to stand for and live out in our daily lives as an example to others.

Now studying for my Master’s, I am planning to continue exploring world war history, as presented in fiction. Primary sources are invaluable for checking up on events, as well as people’s reactions to events, and allow us to make comparisons with how they’re portrayed in fairly recent novels. And on a personal level, it is important to be able to really dig into history and be reminded of the wars, so that we are able to check ourselves and our thinking – to be aware of what we are supporting and representing, because we will pass our opinions and prejudices on to future generations.