│By Olivia McDermott, Gale Ambassador at the University of Liverpool│

As International Women’s Day begins to approach, it seems fitting that we should reflect upon the many ways in which the female experience has changed over time.

Historically, from a patriarchal lens, the female experience has been aligned with ideas of subjugation, inferiority, and passivity. With the societal expectations of marriage and childrearing being deemed as intrinsic aspects of womanhood, up until the early Victorian period, women’s freedoms were extremely limited. However, this began to change by the end of the eighteenth century, as the passing of The Education Act (1870) allowed girls to receive the same education as boys.

Typically, by the 1960s, the introduction of the contraceptive pill in the West provided young women with the freedom to make choices which had previously been denied to them. In this way, twenty-first-century depictions of the female experience challenged ideas of women as passive due to increasing access to education and healthcare presenting new opportunities.

Women’s Experiences Over Time

As an undergraduate English Literature student, I am reminded of the importance that academic education has had on my experience as a young woman. Having entered my final year of study at the University of Liverpool, Gale’s resources have become more valuable than ever. With my dissertation concerning the issues related to modern day approaches of apathy towards the feminist movement within twenty-first-century literature, much of my research revolved around what it means to believe in feminism.

Since the completion of my dissertation, I remain interested in how experiences innate to women have changed over time.

Womanhood as Struggle

Up until the twentieth century, womanhood was largely defined by its sense of struggle. With patriarchal influence dominating all areas of public and personal life, women were unable to both express and assert themselves within society. Though British women gained the right to vote in local elections in 1868, it was not until sixty years later in 1928 that the Equal Franchise Act was passed, allowing all women over the age of twenty-one to be able to vote. In response to the lack of political freedom that women had access to, many women decided to transform their anger into creating suffrage organisations to resist gender oppression.

The most well-known of these organisations was the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), founded by Emmeline Pankhurst and Alice Paul in 1903. During this period, one can see a rise in female anger towards the many injustices that they were presented with. Women’s rights campaigners began moving towards more violent approaches of protest in the early 1900s, such as setting golfing greens ablaze, lighting fires in post-boxes, smashing windows, and disruptive marches.

After plotting to bomb Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George, Pankhurst was sentenced to three years imprisonment in which she conducted several hunger strikes. Unfortunately, the years of lecturing, protesting, touring, and the hunger strikes during her prison stays took their toll, and in 1928, Pankhurst passed away. Although Pankhurst’s life was certainly far from the life of an ordinary woman during this time, it offers us a reminder of how pain and struggle have been so embedded within the female experience, particularly up until women were able to vote.

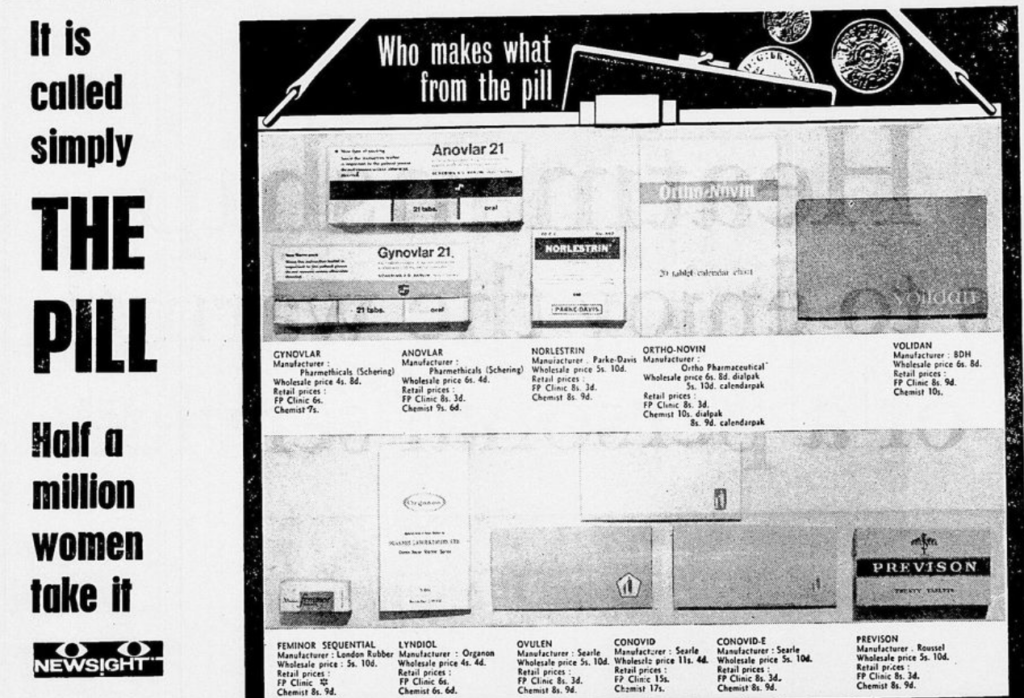

The Magic Pill

By 1961, the introduction of the contraceptive pill in the UK meant that women could now choose not to conform to the expectations of marriage and childrearing. Though other forms of contraception had been available previously, they had largely been dependent on men, whereas now women had control over their own reproductive health.

Abortion was also legalised in 1968, which meant that women also had autonomy over their own bodies and the healthcare they received. This period of increasing freedom and gradual political change is often deemed to be the beginning of the Sexual Revolution.

It is important to note that many scholars continue to debate to what extent the sixties were as liberating for women as we perceive them to be today. There still seemed to be a divide between the women who society provided with the most freedom. For example, it was mostly only middle-class, married women who were eligible and could afford the pill. It was not until 1975 that the contraceptive pill became more widely available.

In this way, it is essential to understand that although attitudes towards women and sexual agency were changing, this period perhaps represents more of the beginning of something rather than an end to inequality.

Girlbossing Her Way to the Top

From the 1800s to the 1900s, one can see changes to the lives of women enacted through law, healthcare, parliament, and medicine. Arguably, one of the most drastic impacts on the way women were viewed in society began around the same time that the idea of feminism as a political movement was introduced.

Predating the twentieth century, the feminist movement insisted on legal and political equality for women, but by the 1990s, there was more importance placed on the idea of women having autonomy over their own bodies and over the choices that they made within their own personal and professional lives.

As feminism began to interact with the rising influence of neoliberal ideologies, the notion of hyper-individualism pre-empted the growing divisions between different kinds of women. Fuelled by ideas of competitivity, neoliberal feminism often failed to acknowledge that the female experience was dependent, not only upon sex, but also on aspects such as class, ethnicity, sexuality, and race.

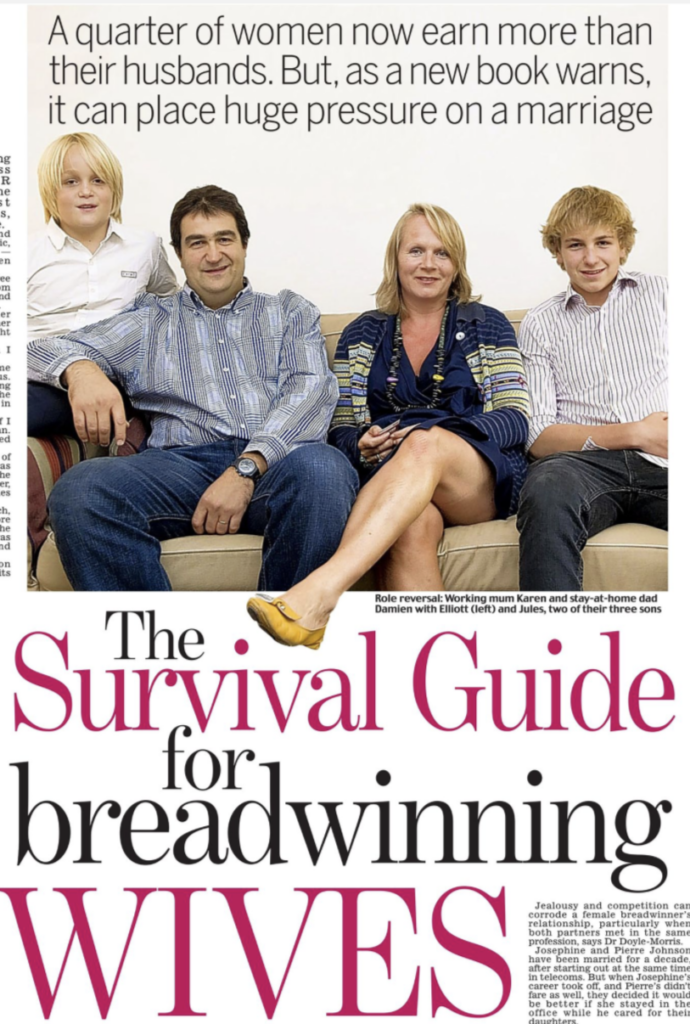

Only certain women who conformed to the monolithic expectations of a white patriarchy were therefore able to break through the glass ceilings of inequality within the workplace. By the end of the twentieth century, the different female experiences at work continued to widen depending on the level of one’s conformity to heteronormative ideals.

Postfeminist Allyship and Intersectionality

As political emphasis on the individual continues to increase, much of the current postfeminist discourse surrounds the idea of the female body as a business model; one that can be used to transgress power structures. However, in conforming to oppressive gender structures, we must ask the question of how empowering such an idea can be. Self-transformation through using extensive beauty products, completing obsessive exercise regimes, and competing tirelessly against other women has long lasting implications on the female experience.

Though many of the newspaper segments referenced suggest that conformity to narrow feminine ideals should be celebrated as liberating, the impact of intersectionality on the female experience must be highlighted. The only thing that unites all women is sex, and so beyond this, other personal circumstances must be considered when examining how the female experience, has and continues to change over time.

If you enjoyed reading about how female experiences have changed over time, then check out these posts:

- Using Literary Sources to Research Late Nineteenth-Century British Feminism

- An Exploration of Women’s Liberation: Insights from Gale Primary Sources

- Using Archives Unbound to Explore the Agency of the Oppressed

Blog post cover image citation: “Time to Grow up.” style. Sunday Times, 18 Jan. 2004, p. 24[S12]-25[S12]. The Sunday Times Historical Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/FP1801132703/GDCS?u=livuni&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=1b6699b6