│By Lucy McCormick, Gale Ambassador at the University of Birmingham│

Using literary sources – such as newspapers, journals, pamphlets, and periodicals – to research feminism in late nineteenth-century Britain is a valuable way to enrich historical scholarship. Regarded as intellectually inferior to their male counterparts, women’s voices had long been deemed unimportant and thus excluded from mainstream media. However, by the second half of the nineteenth century, the intensification of debates pertaining to the ‘Woman Question’ rendered women not merely objects, but also participants, in arguments about the rightful role of women in British society.

Literary sources offer historians an important opportunity to better understand women’s entry into the public sphere, their political agendas, and the emergence of feminist thought. Fortunately, Gale Primary Sources affords access to a wealth of these sources, facilitating myriad ways in which to develop the history of late Victorian feminism in exciting new directions.

Eminent Women

The Women’s Studies Archive provides a launchpad for historians interested in late nineteenth-century British feminism. This is subdivided into several collections, such as ‘Voice and Vision’, in which a monograph entitled Brief Epitomes of the Lives of Eminent Women by Rose Somerville can be found. Published by the Women’s Printing Society in London in 1896, this text offers short biographies of Josephine Butler, Frances Power Cobbe, and Sister Dora. The three women upon whom Somerville focuses have become venerated in feminist historiography as early proponents of ‘First-Wave Feminism’, but it remains a worthwhile endeavour to explore their reception in their own historical moment.

‘Feminism’ was a relatively new and thus tentatively used term in this period, so historians should be cautious about anachronistically imposing this political identity upon these women. Yet this only deepens the value of the source, because it elucidates not only the diverse ways in which women advanced campaigns for their rights, but also how they were culturally celebrated by other women in the same period. This source draws a rich picture of the networks women forged with their feminist foremothers, inculcating a strong sense of their identity as feminists.

From this source we learn that, before the end of the nineteenth century, individual women had gained sufficient public esteem to be deemed worthy of monographic attention. Perhaps this source could inform an argument situating the origins of British feminism in the late nineteenth century, thereby challenging historians who anchor it in the formation of the Women’s Social and Political Union and formal beginnings of the suffrage movement at the start of the twentieth century.

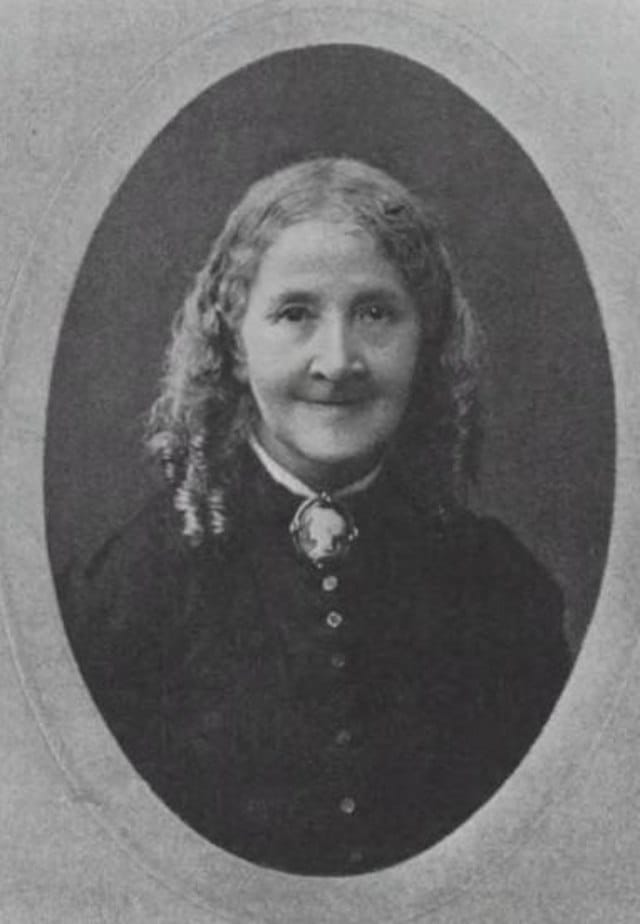

Josephine Butler

Somerville commended Josephine Butler as the ‘champion of Social Purity, and a representative woman of this century’. Parliament passed three Contagious Diseases Acts in the 1860s to stem the spread of venereal disease by authorising police officers to arrest any woman they suspected of prostitution. This legally obligated women to submit to invasive medical examinations. Believing that this licensed men but punished women for prostitution, Butler became the Secretary of the Ladies’ National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts.

According to Somerville, Butler ‘bravely came forward’ to ‘[stand] before the eyes of the whole world while every vile and odious epithet the basest could invent, was flung at her’. In the face of vitriol from those who believed women had no place in the public sphere, Butler was integral to the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts in 1886 – for which, this source reveals, she was celebrated as an ‘eminent woman’ in proto-feminist thought.

The Feminist Press

Many early feminists capitalised on the fin-de-siècle enthusiasm for female journalism to author, publish, and distribute their own magazines, journals, and periodicals. The Women’s Penny Paper, for instance, was a feminist magazine operating between 1888 and 1890. It is an especially useful source because it reveals the issues which characterised feminist thought at the end of the nineteenth century. The feminist press devoted considerable attention to defining and delimiting its ideology.

In an article entitled ‘A Woman on Women’s Rights’ published in 1890, the author (credited only as ‘A. J. M. M.’) argued that women’s rights included: ‘recognition of our right to work in many fields of labour hitherto closed to us’; ‘female suffrage’; and ‘equal advantages of education’, among others.

By utilising explicitly feminist literary sources such as these, historians can learn how advocates of women’s rights perceived their own feminist sensibilities. This informs a more nuanced understanding of the emergence of suffrage as a key tenet of feminism in late Victorian Britain. Arabella Shore wrote in the Women’s Penny Paper on 22nd November 1890: ‘As I believe that nothing will be done for Women Suffrage except by devoting ourselves to it, by regarding it as the question which in a Women’s Association ought to precede all others, I make a heartfelt appeal to my sister Suffrageites.’

Evolution of the Feminist Press

A historian could trace the salience of this pro-suffrage rhetoric within the feminist press throughout the 1890s. In 1897, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy confidently declared that ‘we shall certainly win’ the right to vote in Shafts, another feminist magazine. ‘It is time that women should be enfranchised’, she wrote, for the sake of ‘the upward and onward progress of humanity’. Literary sources offer a rich opportunity to analyse the evolution of tone and content of the feminist press. This informs a more detailed understanding of how arguments for suffrage gained traction before the WSPU and its protagonists brought the debate to mainstream national attention.

Literary Sources

Diversifying one’s source base across literary forms when researching late nineteenth-century British feminism is a useful way to enrich historical research. Feminism galvanised momentum in literary sources, in which women were able to circulate their ideas and make compelling cases for their rights. Historical analyses of this rhetoric in late nineteenth-century literary sources provides a valuable portal into burgeoning feminist thought, grounding the great feminist achievements of the twentieth century in the final decades of the nineteenth century.

If you enjoyed reading about sources for feminist historical research, check out these posts:

- Researching and Teaching Women Writers Using Eighteenth Century Collections Online

- New Zealand – Trailblazers in Women’s Suffrage

- Introducing ‘Women’s Studies Archive: Voice and Vision’

Blog post cover image citation: “The Women’s Penny Paper.” Women’s Penny Paper, vol. 3, no. 108, 15 Nov. 1890, p. [49]. Women’s Studies Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/UWHJKC681395290/WMNS?u=bham_uk&sid=bookmark-WMNS&xid=6d886610.