│By Pollie Walker, Gale Ambassador at the University of Liverpool |

Students at the University of Liverpool are able to efficiently and easily research and evaluate primary source documents using Gale Primary Sources. I am studying International Politics and am currently studying a module on political violence. Reaching Gale Primary Sources via the Liverpool University library page, I was able to examine a vast wealth of information on political violence. In this blog post I’m going to explore some instances of political violence around the world, and how the individuals involved sometimes ended up in politically powerful positions. Any student can use the Gale resources available at their institution to undertake research; the use of original, primary source documents is often the key to reaching the highest grades.

How did I find the articles I used for this research?

I began my research by simply searching “political violence” in Gale Primary Sources. I then decided to look specifically at newspapers, as this type of archival resource covers a wide time span, and has additional benefits such as the ability to track the development of arguments and analysis over time in a particular paper – or contrast views in different papers about the same news story.

Sinn Fein and Ireland

Using The Times Digital Archive enabled me to access information from the late 1990s about political violence. The article ‘How political violence gives way to organised crime’ explores the link between political violence and government in Ireland, with comparisons made with the situation previously experienced in South Africa. The article argues that giving previously violent groups political power can lower the prevalence of political violence – but it may lead to an increase in non-political organised crime. I was particularly interested in the discussion around how Sinn Fein (the political wing linked to the IRA, the ethno-nationalist separatists in Northern Ireland) ended up on the administrative board in Ireland. It leads me to wonder whether it is a negative or positive thing when political violence is rewarded with political power: is Sinn Fein’s political power a positive development in the history of Ireland? Or something that should be restricted because of their violent past?

South Africa and Zimbabwe

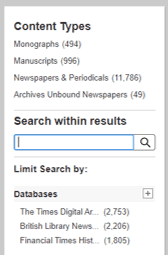

The African National Congress (ANC) has been the ruling political party of post-apartheid South Africa since the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994. Before this move into political power, however, Nelson Mandela was considered (and treated as) a terrorist. In relation, I also read about the struggles around power and political violence in Zimbabwe. The article below from the Financial Times Historical Archive suggests “political violence and intimidation was so widespread and severe that conditions do not exist at present for credible elections” and “the effects of violence and attempts at political intimidation have undermined trust among many Zimbabweans in the secrecy of the ballot; and have raised fears of retribution for voting against the ruling party.” It was interesting to read about the power dynamic in another African country, to help me compare and contrast with the situation I had previously read about in South Africa.

Mallet, Victor. “Zimbabwe Political Violence and Intimidation ‘Widespread’.” Financial Times, 23 May 2000, p. 14. Financial Times Historical Archive https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HS2301145184/GDCS?u=livuni&sid=GDCS&xid=658d92e8

Nazi Germany

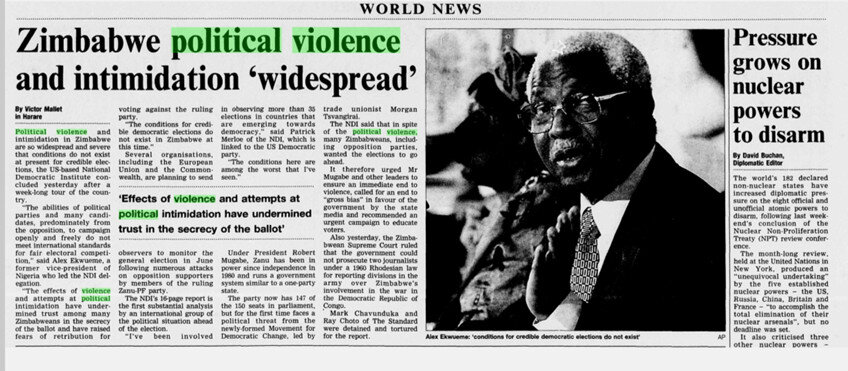

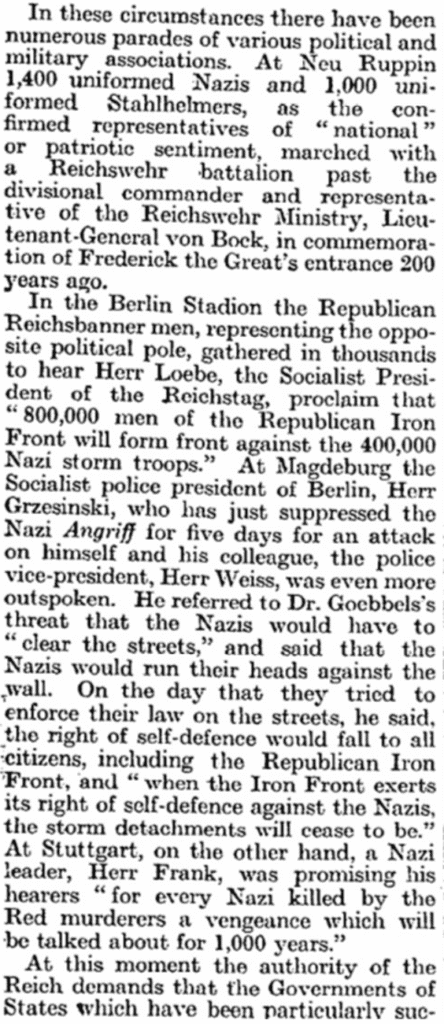

Whilst there are many examples of political violence leading to political power in history, one of the most infamous is how the Nazi Party rose to power in the 1930s. I was able to quickly find an article in The Times Digital Archive from 1932 on political violence in Germany. This article was written before Hitler became the Chancellor of Germany. This article clearly describes the skirmishes and serious violence the Nazi party were involved in, in the early 1930s – many of which against rival political parties or institutions, such as attacking the offices of the Socialist Vorwärts. Indeed, The Times Berlin correspondent reports “assaults [are] now daily occurring”. At this point, there was still a great deal of opposition to the Nazis from Socialists:

“In the Berlin Stadion the Republican Reichsbanner men, representing the opposite political pole, gathered in thousands to hear Herr Loebe, the Socialist President of the Reichstag, proclaim that “800,000 men of the Republican Iron Front will form front against the 400,000 Nazi storm troops.””

The article also describes a weekend of violence which saw the death of both Nazis and Republican Reichsbanner men, and 60 people were wounded. Much of the Nazi violence was enacted by the Brown army, the Nazi Party’s original paramilitary wing which played a significant role in Hitler’s rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s. It is interesting that President Von Hindenburg had recently signed a decree releasing the Brown Army from suppression, on the basis that their violence would cease – yet it clearly didn’t.

Whilst I have previously studied WWII, I knew less about the early days of the Nazi party, and found this additional insight into political violence in Germany fascinating. My research with primary sources has given me far greater understanding of the political violence exhibited by the Nazis in the early days, exhibiting a clear link between the use of political violence and politics of state.

Scholarly perspectives on political violence

I was also able to unearth scholarly perspectives on political violence in the archives. This article in The Telegraph Historical Archive, for example, was written by Peter Gill in 1978 and reviews a study written by Dr Clutterbuck, a retired General who in 1978 was working as an academic specialising in the study of political violence in the Department of Politics at the University of Exeter. The article tackles different perspectives on how political violence has been punished, and interestingly found that the British courts had been ‘surprisingly lenient in punishing political violence’. The article provides a general overview of political violence over many years, and the figures demonstrate how only a small percentage of those convicted of political violence are ever imprisoned. The reasoning from magistrates seems to be that political violence is understood to be morally more forgivable than violence for personal gain. In contrast, Dr Clutterbuck’s argument is that most criminals had suffered deprivation, whilst those who commit political violence will often have had many opportunities open to them. Interestingly, the reviewer chooses to highlight Clutterbuck’s point that political violence is actually far from heroic: “the book serves to remind readers of the reality behind some celebrated acts of political violence that have already passed into…mythology as part of the heroic struggle.”

Interested in reading more about the danger of political power, using primary source archives? Check out Gale Ambassador Ellen Lesser’s post “What we may expect”: The Corrupting Power of Power.

Blog post cover image citation: Adolf Hitler, German dictator, ascending the steps at Buckeberg flanked by banner-carrying storm troopers who display the Nazi swastika. “Adolf Hitler, German Dictator.” Gale In Context Online Collection, Gale, 2019. Gale In Context: College, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/REANQM067587447/GPS?u=webdemo&sid=GPS&xid=935b502e