│By Caley Collins, Gale Ambassador at University College London (UCL)│

Italian Futurism was an avant-garde movement founded in 1909 by F. T. Marinetti upon the publication of his tract The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism. The Futurists aimed to radically break from the past and create new types of literature, art, photography, and even music. They intended to glorify technology, aggression, and speed while destroying artistic and literary conventions.

The movement officially ended in 1944 with Marinetti’s death, however it is often considered to have had two phases. The first, more valiant phase is perceived as having ended in 1916 upon the deaths of several key members of the movement, including Umberto Boccioni, in WWI. In the subsequent years, Futurism moved in a different direction, allying itself with the Italian National Fascist Party and thus occasioning its own downfall. Using Gale Primary Sources, this post will explore the different facets of Futurism’s attempted creative emancipation from the past, alongside the movement’s legacy.

Futurist Literature

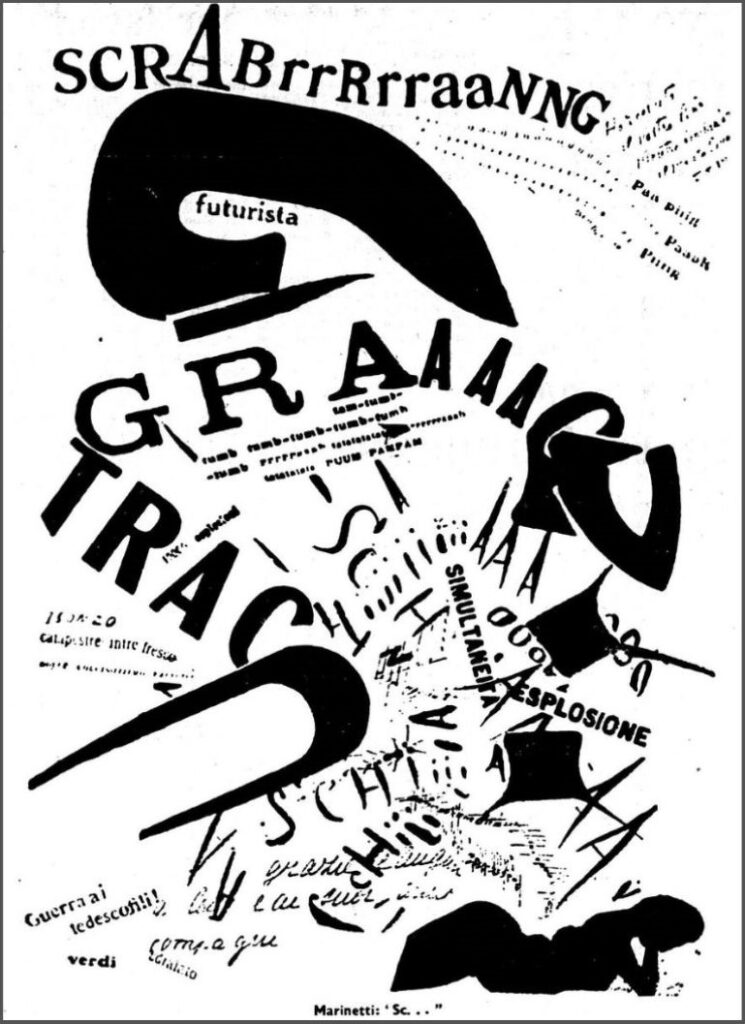

The Futurist movement initially focused on literature, including both its content and the presentation. Even without having read Marinetti’s manifestos, it is easy to see the radical nature of his work when presented with his poetry, or in this case, even the cover of one of his poems.

![Morris, Roderick Conway. "The Revenge of the Futurists." International Herald Tribune [European Edition], May 9,](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Blog-Post-Image-2.png)

Arguably Marinetti’s best known Futurist poem, ‘Bombardamento di Adrianopoli’ is a war poem inspired by the siege of Adrianople, which lasted from 1912-1913. Not only does this poem elevate war, which was one of Marinetti’s key aims for the Futurist movement, but even from the cover the author’s radical use of typography is clear. The concept of ‘parole in libertà’, or ‘words in freedom’, involved the eradication of standard syntactical rules, as is made evident both in Marinetti’s Destruction of Syntax – Imagination without Strings – Words in Freedom manifesto and here through his use of invented onomatopoeic words.

As can be discovered by reading the poem, ‘zang’ and ‘tumb’ reflect the noise of the bombs and bullets of warfare, with their size directly corresponding to the volume of the sounds that Marinetti describes, whilst their position on the page indicates the direction they are coming from.

Although this poem clearly idolises war, it also adheres to other central Futurist tenets in its admiration of the new technology being used in warfare, alongside the speed and dynamism that accompany modernity. As is stated by the Financial Times’ Jackie Wullschlager, Futurism emphasised ‘movement and machines’, with the former being especially fundamental to the development of art within Futurism.

Futurist Art

![Morris, Roderick Conway. "The Revenge of the Futurists." International Herald Tribune [European Edition], May 9, 2009](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Blog-Post-Image-3-1024x748.png)

In this 1911 painting by Umberto Boccioni, the viewer’s attention is immediately drawn to the work’s fragmentation. Entitled ‘States of Mind: Those Who Go’, Boccioni’s main focus is the movement prompted by the action of leaving, with this being depicted through narrow brush strokes that illustrate the speed of this motion.

Additionally, each face has multiple iterations, reflecting their consecutive motions and thus also capturing the chaos of the modern world, as collective and individual movements occur swiftly and simultaneously. As is stated in New York: The Italians in New York, the Futurist painters ‘strove to introduce the time element into painting, along with a general expression of the hectic violence of their era’.

This assertion is substantiated by Carlo Carrà’s 1913 painting ‘The Red Horseman’, which is featured as the header image for this blog post. Carrà multiplies each part of the horse and rider to highlight their frenzied action, with this technique being known as ‘lines of movement’. As affirmed by Marina Vaizey in a 1972 article on Futurism, Marinetti inspired ‘an urban art of intense vitality, and “dynamism” [was] a much favoured word’.

Futurist Photography

These ‘lines of movement’ were also central to Futurist photography. Alongside Marinetti, several other Futurists wrote manifestos outlining their views on how Futurist principles should be implemented in their specific fields. Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s 1913 ‘Fotodinamismo’ asserts that photography should be artistic, with the depiction of subjects in their various phases of movement creating a ‘sintesi di traiettoria’, or ‘synthesis of movement’.

![Bragaglia, Anton Giulio. Fotodinamismo Futurista. 3rd ed., Nalato, [1911].](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Blog-Post-Image-4.png)

Although this manifesto is written in Italian, using the ‘View Options’ tab in the Gale menu will allow the reader to choose to view both the image of the manifesto and the OCR plain text version. The plain text can then be translated using a translator extension within a browser or an external translating service. Although the OCR confidence for this manifesto is only 50%, meaning that there are some mistakes and inconsistencies due to an inability to read certain characters or damage to the manuscript, a translation of the OCR for Bragaglia’s work will allow the reader to understand the majority of what he has written.

![Bragaglia, Anton Giulio. Fotodinamismo Futurista. 3rd ed., Nalato, [1911].](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/No.-5-border-1024x472.jpg)

Continued Relevance

Futurist ideology also extended to politics, as seen by Mussolini’s discussion of the movement and their alliance, and thus can be used to understand the popularity of Fascism. The Futurists joined in with Fascist protests, leading to several key Futurists being arrested for partaking in violent demonstrations. Their desperation to create something new and break with the past was thus applied both creatively and politically, giving modern viewers a glimpse into the collective Italian psyche during the beginning of the twentieth century. Coupled with the Futurist idolisation of military strength, Mussolini’s rise to power is consequently easily explained by referring to the movement’s doctrines.

As Marinetti himself wrote for The Listener, ‘by rejuvenating the Italian mind and artistic sensibility and by making them more alert, we also undertook to rejuvenate intellectuality throughout the world’. Futurism inspired many subsequent artistic and modernist movements, such as Surrealism and Dada, through its rejection of artistic conventions and insistence upon innovation. When writing for The Daily Telegraph in 1973, Terence Mullaly stressed the movement’s continued relevance, arguing that the ‘Futurists may not have won the day, but their influence remains potent’ as they continue to inspire further creativity today.

I hope that this blog post has both inspired you to learn more about Italian Futurism and highlighted the extensive nature of Gale’s Primary Sources. From manifestos in Italian to critical reviews of art exhibitions, there is always more to discover!

If you enjoyed reading about Italy or avant-garde art and literature, check out these posts:

- Tourism and Technology within The International Herald Tribune Historical Archive

- Tracing the Legacy of William Blake with British Literary Manuscripts Online

- Leaning into The Great Gatsby and Other Primary Sources

Blog post cover image citation: Morris, Roderick Conway. “The Revenge of the Futurists.” International Herald Tribune [European Edition], May 9, 2009 – May 10, 2009, p. 19. International Herald Tribune Historical Archive, 1887-2013, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/UGQAEO052733728/GDCS?u=ucl_ttda&sid=bookmark-GDCS&pg=19&xid=3f87e3dd