|Rosa Ferreira, Digital Product Trainer|

Armando Dias De Castro, my avô – my Portuguese grandfather – was a man full of life. He was warm, funny, always ready with a story or a joke. He was also the kindest man you’d ever meet. But when it comes to his time in Angola, I’ve got nothing. No stories, no memories. If he ever spoke about it, I must have been too small to notice, or the words just never stuck.

My uncle, however, recalls many conversations. That makes me believe my avô must have shared his experiences, at least in fragments, though they slipped past me.

It is this gap – between the grandfather I knew and the silence that lingers – that has drawn me into the archives.

1964: A Turning Point

By the early 1960s, the Angolan independence struggle was underway. Movements like the MPLA (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola) and FNLA (Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola) were active; the Portuguese state held tight control; censorship was strong, and opposition punished. Archives have become my way of listening in.

My avô left the army in 1964. For him, it was an ending; for Angola, it marked the edge of something much larger.

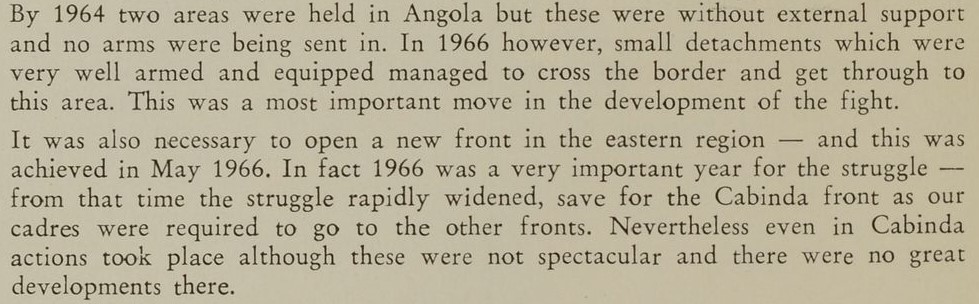

As MPLA fighter Lúcio de Lara later reflected, 1964 was a very difficult year as “two areas were held in Angola but these were without external support and no arms were being sent in”. It was only in 1966 that the movement in the east of Angola became consolidated.

His words capture a moment of fragility: a conflict still unsettled, not yet rooted but already demanding sacrifices.

I cannot know what my avô felt when he returned home – relief, unease, perhaps nothing at all. Yet the timing feels haunting. His departure coincided with a war that was only just beginning to harden.

Freedom Fighters or “Terrorists”?

Among the most striking documents I uncovered in Gale Primary Sources’ archives was an ANC pamphlet, not written about Angola directly, but about the language used to undermine liberation struggles across Southern Africa:

“In Algeria they were called terrorists; in Vietnam they were called bandits; in Kenya they were called criminal gangs… They try to destroy us by swear words because they fear what we really are – freedom fighters.”

![Extract from 'These Men Are Our Brothers, Our Sons: They Fight for the Freedom of the People' [typescript] Political Pamphlets from the Institute of Commonwealth Studies: South Africa](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/These_men_are_our_brothers_our_sons.jpg)

That distinction – terrorist or freedom fighter – was more than rhetoric. It shaped how men like my avô would have understood the conflict around them, and how those fighting for independence were perceived by the outside world.

Everyday Resistance

War was not only fought with rifles. In his testimony, Lúcio de Lara painted another picture: schools built in the bush, makeshift hospitals where soap was traded for maize, and young men who slipped lessons in Marxism between bursts of laughter.

Steve Valentine’s The War in Angola: Portugal Faces Defeat (1969) offers a glimpse from the other side of the frontier:

He describes the discipline and determination of guerrilla fighters, including Samuel Chiwale:

“Samuel Chiwale said that political organisation was the main task of the party. ‘Without the support of the people we could not operate,’ he said. ‘With their support we cannot be beaten.’”

What comes through in these accounts isn’t just the fighting. It’s the way people kept each other going – sharing food, finding ways to laugh, refusing to give in. The movements survived because ordinary people stood beside them. Reading those words, I felt pulled into a world that looks nothing like the Portuguese reports of calm and control.

Perspectives in Contrast

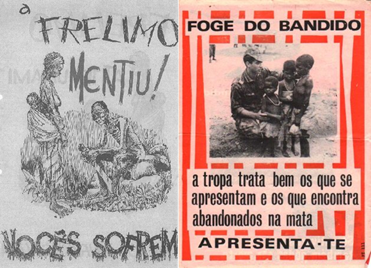

When I placed the guerrilla voices next to the Portuguese records, the contrast was startling. The ANC and UNITA sources spoke of endurance and organisation. The Portuguese materials, by contrast, sought to shape perception as much as they reported facts.

Some propaganda urged Angolans to flee the so-called “terrorists” with promises that Portuguese troops would care for them. Other leaflets turned against FRELIMO, the liberation movement in Mozambique (also a Portuguese colony), telling local communities: “FRELIMO lied to you, you are suffering.”

The message was sharp and manipulative: those who fought for freedom were cast as deceivers, their cause reduced to betrayal.

Looking at these documents side by side helped me understand something essential. The silence around my avô’s service was not only a private one. It belonged to a wider world shaped by censorship, distortion, and fear.

My avô’s story will always be incomplete. Too much was never said, and too much was obscured by propaganda. What I have are fragments: my uncle’s memories, brittle photographs, and words preserved in archives.

I may never know his thoughts on Angola. Yet perhaps what matters is not what he said, but what we can still learn: about truth and its distortions, about the fragility of memory, and about how ordinary lives – like my avô’s – brush against the sweep of history.

The archive cannot give me his voice. But it gives me echoes. And sometimes, echoes are enough.

If you found it interesting reading about the decolonisation of Angola, check out these posts:

- A Window Into Decolonization: Perspectives From Formerly Colonised and Commonwealth Regions

- Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories

- Studying Colonialism in Complementary Archives: Nineteenth Century Collections Online and Decolonization

Blog post cover image citation: A collage of photographs from the Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories archive and personal photographs.

Personal family photos included in this post with kind permission of the author.