│By Elizabeth Gaglio, Digital Product Trainer|

“What is it actually about?” the bookseller asks me as we scan the shelves in the British History section.

“Graffiti in the eighteenth century,” I say.

Admittedly, it’s a topic I may have thought was out of place not long ago. Graffiti, by nature, is often thought of as impulsive and temporary; an expression of a moment, publicly written somewhere it doesn’t belong. How much can we really know about writing, marks, and art that have long since been washed away or painted over?

In the book I’m looking for, Writing on the Wall: Graffiti, Rebellion, and the Making of Eighteenth-Century Britain, historian and author Madeline Pelling shares some specific examples of how “lost voices”, especially of those who were not otherwise published and preserved, can still be heard and seen today. The bookseller spots the book, aptly hidden in plain sight, and uses the ladder to bring it down to me.

Graffiti in the eighteenth century was especially prevalent and impactful, driven by rising literacy rates and societal change. It is, however, only part of the long and enduring history of graffiti. A history reflective of human nature and the overwhelming desire to leave one’s mark.

Historians studying graffiti identify certain characteristics that have made graffiti a lasting medium of expression from ancient times to modern day. Crucially, graffiti is accessible and largely anonymous, inviting a wide range of participants. And when it’s witty and collaborative, the stories told through graffiti certainly leave a lasting impression.

Accessible and Common

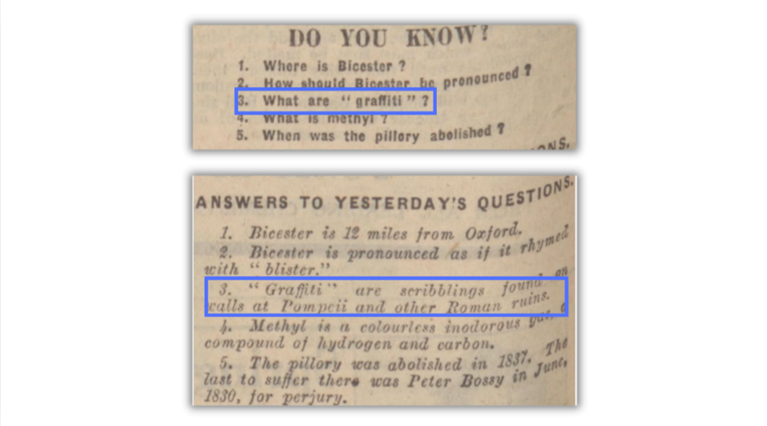

Even though graffiti has existed as long as people have been making marks on things, the term “graffiti” was only adopted into the English language in the middle of the nineteenth century. In 1921, The Nottingham Evening Post featured the somewhat niche technical term in their daily trivia section, “Do You Know?”. The question asked readers, “What are ‘graffiti’?”. The correct answer was: “‘Graffiti’ are scribblings found on walls at Pompeii and other Roman ruins.”

“Graffiti”, of course, has a broader definition today, but the origin of our modern usage comes from one of the most famous sites of ancient graffiti, Pompeii. The bustling city was famously frozen in time after the sudden and catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

In 1851, while excavating the entombed city, archaeologists used the Italian word “graffio” or “graffito” (singular), meaning “a little scratch”, to describe the individual messages they were seeing on the walls. The collective scratchings, or “graffitti” (plural), tell a story of daily life that is recognisable nearly two thousand years later. Messages of greetings and love alongside insults and political commentary are not so different from what we see on the street and online today:

“Gaius Pumidius Diphilus was here.”

“Long Live the Emperor”

“Pheobus – may you fall ill.”

“Beware, Timinia: thieves!”

“We are cold.”

The Ancient Graffiti Project documents and maps thousands of written and figural graffiti in Herculaneum and Pompeii. The project’s Director, Rebecca Benefiel, PhD, has noted that what she finds extraordinary about graffiti is how common it is. Anyone with a sharp instrument or charcoal, could participate in sharing their ideas.

Making marks in public spaces continued to be a part of normal life throughout history. In Medieval times, people in Britain carved symbols to ward off evil, and they drew animals and crops to share knowledge. The walls of Scalan Mill in rural Scotland are filled with notes from the workers in the early nineteenth century. Planks of wooden doors acted like pages of a record book, with measurements, calculations, and tips.

Early examples of graffiti reflect the wide range of participants, their thoughts, encounters, and even boredom. As an ancient Pompeiian wrote, “I’m amazed, oh wall, that you haven’t fallen into ruins since you hold the boring scribbles of so many writers.”

Anonymous and Uncensored

While “Gaius was here” has been a popular style of graffiti throughout history, a desirable feature of graffiti is that it can be, and largely is, anonymous. One of my favourite stories from Madeline Pelling’s book is “Wilkes’ 45”. She documents how in the spring of 1763, the number 45 started showing up on walls and windows throughout London. Even carriage doors were sprawled with the number 45, causing drivers to unknowingly carry the message across the city.

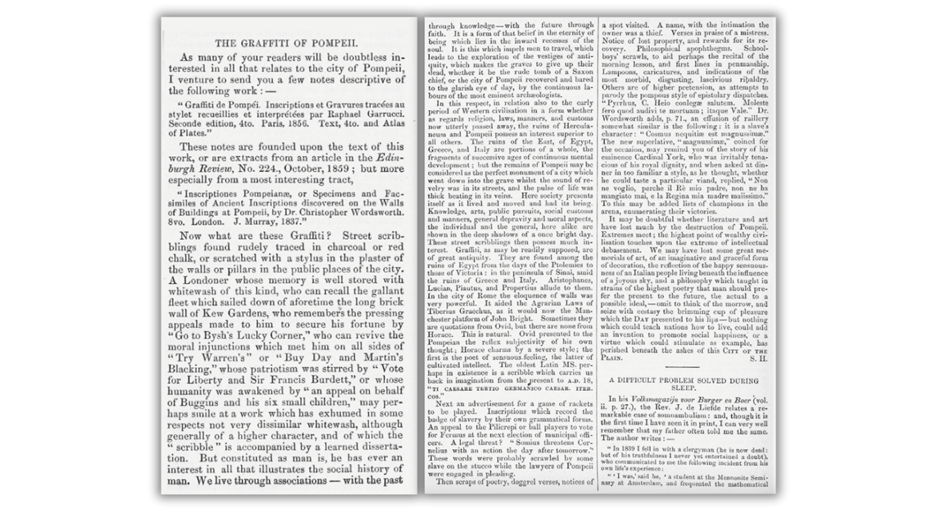

What was the importance of 45? It referred to Issue 45 of The North Briton, in which MP and journalist John Wilkes spoke out against King George III. Wilkes’ growing number of supporters wrote 45 on everything they could to bring attention to the issue and its sentiments without explicitly breaking the law by speaking out against The King. John Wilkes, however, was charged with seditious libel and had to flee to France.

![Extract from Wilkes, John. The North Briton. ... Vol. 3, London [sic]: printed by especial appointment for E. Sumpter. And, Dublin: re-printed, and sold by the booksellers, 1763.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/TheNorthBriton45-1.png)

Boisterous graffiti, like “Wilkes’ 45”, was very popular in eighteenth-century Britain. People rushed to see messages of gossip and scandals before they were removed or covered. In an effort to preserve the creative messages and spread the graffiti to a wider audience, an anonymous author started writing down and compiling the graffiti messages.

The author published the collection of graffiti as “The Merry Thought” or “The Glass Window and Bog-house Missellany”. The pamphlet was advertised as “faithfully transcribed from drinking glasses and windows in taverns, inns and other public places in this nation”, with contents “relating to love, matrimony, drunken, sobriety, ranting, scandal, gaming, and many other subjects, serious and comical.”

The pamphlet was instantly well-received, and the anonymous author went on to publish multiple volumes. Throughout history, the anonymity of graffiti has allowed for people to share their thoughts without fear of consequences.

Anonymity allows for ideas to be universal, transcending class, race, and gender. It has also challenged our understanding of literacy, when examples of graffiti have been found that were written by groups thought to be illiterate, like women and enslaved people.

Witty and Collaborative

Part of the popularity of “The Merry Thought” or “The Glass Window and Bog-House Missellany” was that is captured witty comments and creative thinking. When reflecting on the graffiti of Pompeii, Dr. Benefiel shares, “There is very much a sense of these being a way to express oneself, not with a huge voice, but with a clever voice.” She has found examples of poetry, puzzles, and word play using famous writings of the time. All creative ways to grab the attention of a passerby, and sometimes to engage them in more dialogue. One ancient graffito says:

“Lovers, like bees, lead a honeyed life.”

The line written in response below says:

“I wish!”

These seem like early versions of what we might see today on a social media thread or a bathroom stall. And, in fact, you can still visit some “bathroom graffiti” from the nineteenth century. A pub in Edinburgh, Scotland has kept the original windows, filled with diamond-scratched messages. If you make your way to the women’s bathroom, you’ll see the window and the names of people who left their marks:

Studying historical graffiti helps us build and weave together multiple narratives of the past, enriching our understanding of the people that lived during the time. Because it was easily accessible for people to leave their mark, and they could do so anonymously, we’re left with authentic thoughts and emotions, both big and small. We also see ourselves, regardless of how modern, with some of the same curiosities, impulses, and ambitions.

If you enjoyed reading about historic graffiti, check out these posts about creative writing and personal narratives:

- Paradise Found: Exploring Historical Maps and Travel Writing

- Romantic Writing: This History of Valentine’s Day Cards

- Lesser-Known Narratives and Everyday Histories in Archives Unbound

Blog Cover Citation: Zhou, Ziyi. “Queen Animated Illustration.” Unsplash, 2 May 2021, https://unsplash.com/photos/queen-animated-illustration-bmyb072Ug0c.