│By Tabetha Wood, Gale Ambassador at Durham University│

As I approach the final term of my history degree, I feel particularly passionate about the empowerment of minority groups through a representation of their past experiences. I saw my dissertation as an opportunity to fuel this passion and by investigating the ‘whiteness’ of American beauty standards between 1945-60, I represented the adversity African American women encountered in this realm, an obstacle that women of colour continue to face today.

Whilst it is crucial to acknowledge the discrimination African American women faced, it is also important to avoid reducing these women to passive victims in historiographic representations. Using Gale Primary Sources, this blog post will honour the life and work of Madam C.J. Walker, a maverick of the American beauty scene.

Businesswoman, Philanthropist, Inventor

African American women were far from passive in their response to discrimination; they showed initiative and agency in response to racist beauty standards. Gale Primary Sources has been an indispensable tool in my dissertation research and its objective to uncover the untold stories of African American women’s strength and resistance.

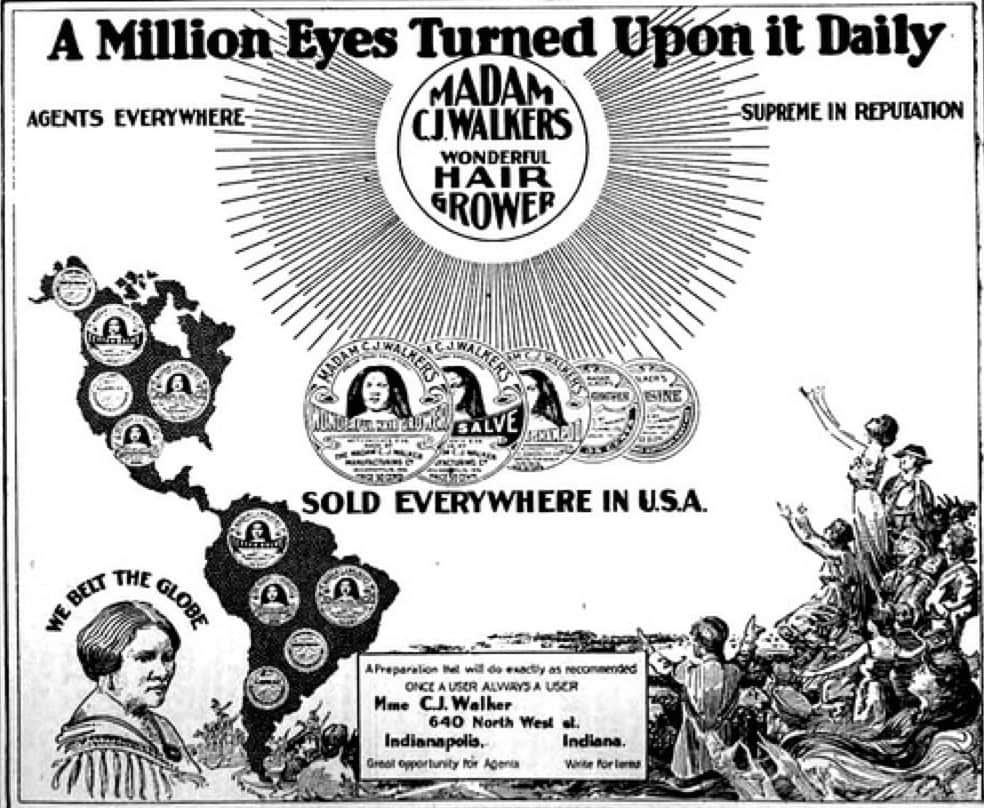

A 1989 source found in Gale’s Archives Unbound collection describes Madam C.J. Walker as a “[businesswoman], philanthropist, inventor,” and “confidence builder”. Madam Walker is best known for developing and marketing a line of beauty and hair care products specifically designed for Black women. At a time when ‘beauty’ was exclusively the domain of white women by the standards disseminated by the dominantly white media, Walker’s curation of products and advertisements that centred around Black women was revolutionary.

The Beauty Standard

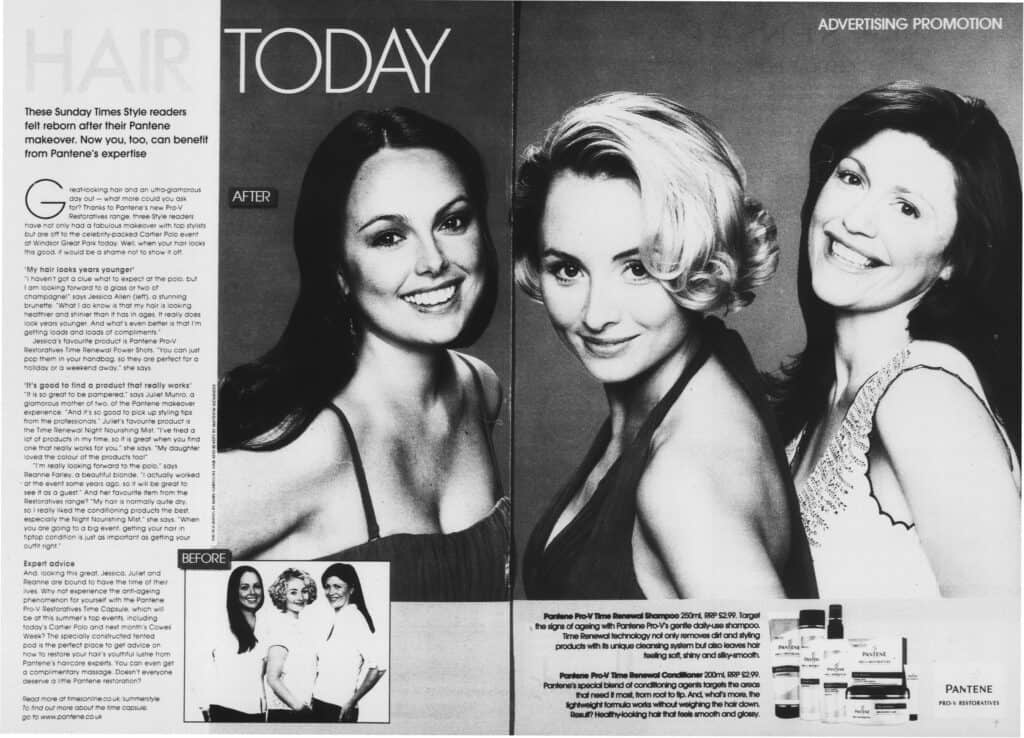

This advertisement reflects the racially coded ‘beauty’ that was encouraged by the media in nineteenth and twentieth century America. Found in the Nineteenth Century Collections Online archive, the source is a 1924 advertisement that featured in New York’s The Designer and the Woman’s Magazine. As this advertisement attests, the media deployed imagery of white women to represent the beauty standard. Black women were excluded from visions of ‘beauty’ disseminated by the dominant media in this period.

Moreover, the language used by this advertisement – “soft, silky, wavy” – to describe “beautiful hair” further asserts ‘beauty’ as exclusively the domain of the white woman. The eulogization of ‘soft’ and ‘shiny’ hair that takes place in this 1924 advert persists in hair adverts today, (see Pantene advert below). Hair products are promoted through the promise of ‘shiny’ and ‘soft’ hair; a hair of this texture is positioned as the ideal to be sought after.

Excluded from this ‘ideal’ is the Afro and tightly coiled hair texture of many Black women.1 Since light reflects more like a mirror on a flat surface, white, straight hair appears ‘shiny’.2 Contrastingly, on an uneven surface, light tends to scatter.3 Therefore, the different curls and angles of each Afro hair strand means that Black women’s hair does not ‘shine’ in the same way that straighter, white hair does.4 As is perpetuated in beauty media today, the ‘beauty’ normed by dominant media in nineteenth and twentieth century dominant media was positioned in opposition to the physiology of the Black woman.

Madam Walker’s Beauty Company

In contrast to the contemporary media, which excluded the Black woman from representations of ‘beauty’, Madam Walker’s beauty company disseminated adverts and packaging that centred around the Black woman.

This Walker product is Madam C.J. Walker’s Vegetable Shampoo found in an advertisement in Archives of Sexuality and Gender. As this source demonstrates, Madam Walker often used herself to model as the face of her products.5

Walker’s products still sought to change the Black woman’s appearance to reflect a closer proximity to the white beauty standard. For instance, the hugely successful product, Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, aimed to make Black women’s hair appear longer, like the flowing locks of the white women asserted as ‘beautiful’ by the contemporary dominant media. However, by using her own face to represent her brand, Walker subverted the hegemony white women possessed over ‘beauty’ in this period.

Walker’s beauty products were created with the African American woman in mind; the dominant media’s exclusion of the Black woman from the beauty realm was subverted by Walker. By showcasing how her products worked on her own body, Walker’s beauty media constructed a beauty standard that was accessible to, and representative of, the Black woman.

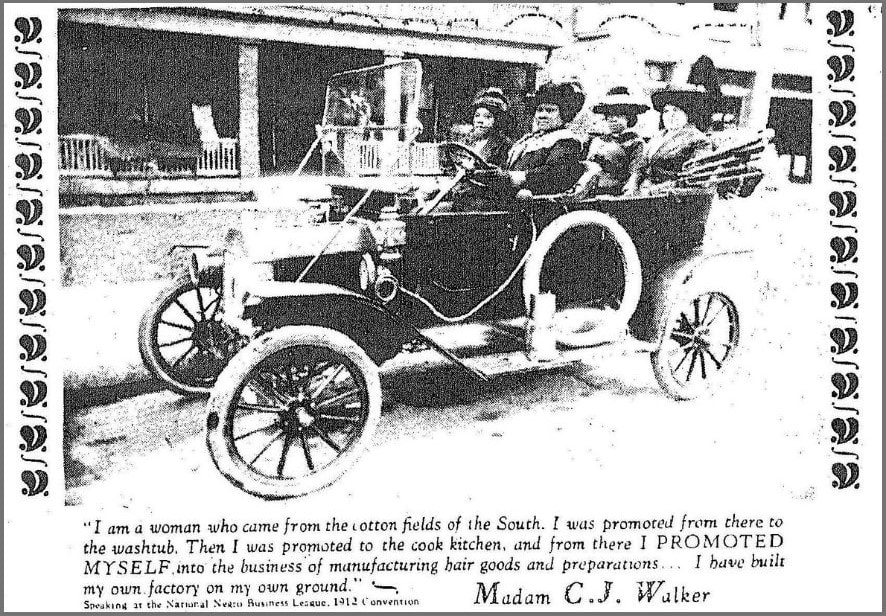

The First Self-Made Black Female Millionaire

Due to her success as a businesswoman, Walker became the first self-made Black female millionaire in America and is seen here driving her Model T Ford in 1912. Despite coming “from the cotton fields of the South”, Madam Walker’s intelligence, fierce determination, and entrepreneurial initiative propelled her to become one of the most successful and influential African American entrepreneurs of her time, revolutionising the beauty industry and empowering countless women along the way.

Madam Walker was also the driving force of many other Black women’s financial enhancement in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Over her lifetime, it is estimated that she employed 100,000 African American women as sales agents and beauticians of the Walker company.6 Far more than simply featuring Black women on the packaging of her beauty products, Walker bestowed upon them a legacy of confidence, economic prosperity, inspiration, and social mobility, transforming lives, and reshaping societal norms.

If you enjoyed reading about Madam C.J. Walker check out these posts:

- Using Archives Unbound to Explore the Agency of the Oppressed

- “Power to all the people or to none”: Grassroots activism in amateur publications written by women, African Americans and the LGBT+ community

- Decolonising the Curriculum with Archives Unbound

Cover Image: C.J. Walker, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hair_grower_ad.jpg via Wikimedia Commons

- Ebuni Ajiduah, ‘Afro Answers: why you don’t need to shine or define your curls and how microlinks work’, gal-dem, (2020), https://gal-dem.com/afro-answers-hair-column-define-curls-microlinks-afro-hair/, (Last Accessed 30/4/24).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Catherine Davenport, ‘African American Women and the Building of Beauty Culture in South Carolina’, Scholar Commons, (2017), https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4201/?utm_source=scholarcommons.sc.edu%2Fetd%2F4201&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages, (Last Accessed 30/4/24), pp. 9-10.

- Noliwe M. Rooks, Hair Raising: Beauty, Culture, and African American Women, Rutgers University Press,(1996), p. 18.