│By Isabelle Partridge, Gale Ambassador at the University of Exeter│

Emotion, nature and individualism are some of the key themes of Romanticism. This cultural movement became popular in Western Europe during the late eighteenth century and was expressed primarily through art and literature. However, the major intellectual movement which preceded Romanticism was the Enlightenment, during which philosophers emphasised rationalism in the pursuit of knowledge. Thus, Romanticism has often been posed as an opposite reaction to the Enlightenment.

Through using Gale Primary Sources, I have gained access to a number of notable works from the Romantic period, from paintings to poems, as well as the opportunity to explore how these works have been perceived since their initial creation. Primary sources highlight how Romanticism was a dynamic and varied movement. Romanticism responded not only to the Enlightenment, but the many political and social developments, such as revolution and industrialization, which had created a backdrop for the turn of the nineteenth century.

Rejecting Rationalism and Harnessing Emotion

The Enlightenment has been described by scholars as a rationalising project, as it championed the search and acquisition of knowledge through reason and logic. The Enlightenment was therefore intricately connected to the period of dramatic scientific advancements from the seventeenth century, known as the Scientific Revolution.

During this period Sir Issac Newton established a mechanistic understanding of the universe in his 1687 work Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Romantic poet William Wordsworth made a direct critique of this approach to the universe in his poem The Tables Turned, found in the second edition of Lyrical Ballads published in 1800. This was a collection of poems published alongside fellow Lake poet Samuel Coleridge and has since been viewed as the beginning of the romantic movement in literature.

The poem demonstrates its scepticism towards the Enlightenment’s traditional pursuit of knowledge by calling on the reader to “quit your books,” and instead embrace nature which offers its own source of wisdom, as well as warning against the dangers of “meddling intellect”.

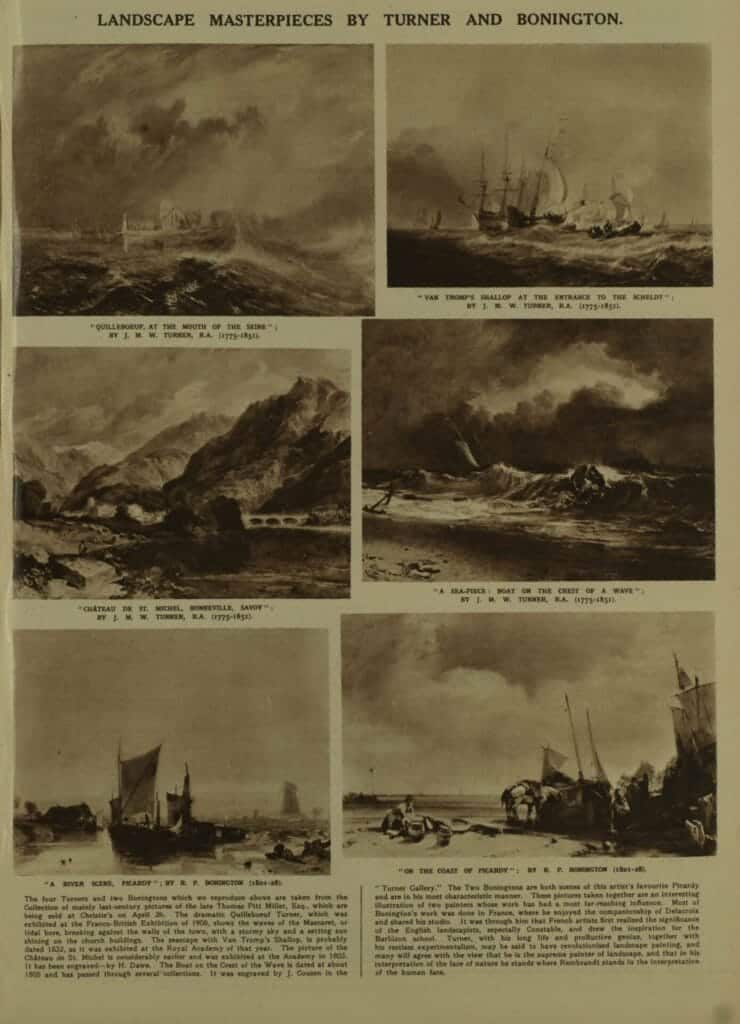

In the field of visual arts, artists began to diverge from neoclassicism, which was popularised during the Enlightenment as it drew inspiration from ancient cultures and emphasised symmetry and harmony. J. M. W. Turner instead produced scenes which were highly emotive and atmospheric through the manipulation of colour and light. Turner is most well-known for his seascapes and by juxtaposing man-made sea vessels against tumultuous waves he highlights the unruly power of nature, evoking a sense of drama and danger.

The impact of his style is expressed in a 1946 issue of The Illustrated London News:

“Turner, with his long life and productive genius, together with his restless experimentalism, may be said to have revolutionised landscape painting, and many will agree with the view that he is the supreme painter of landscape”

Revolution in Politics and Art

While romantic artists drew obvious inspiration from the natural world around them, they also responded to the unique political and social climate in Western Europe at the turn of the nineteenth century. One major event of this period was the French Revolution. This actively began in 1789 with the Estates General which overthrew a despotic monarchy in France and aimed to leave behind the ancien regime that deeply stratified French society socially and economically.

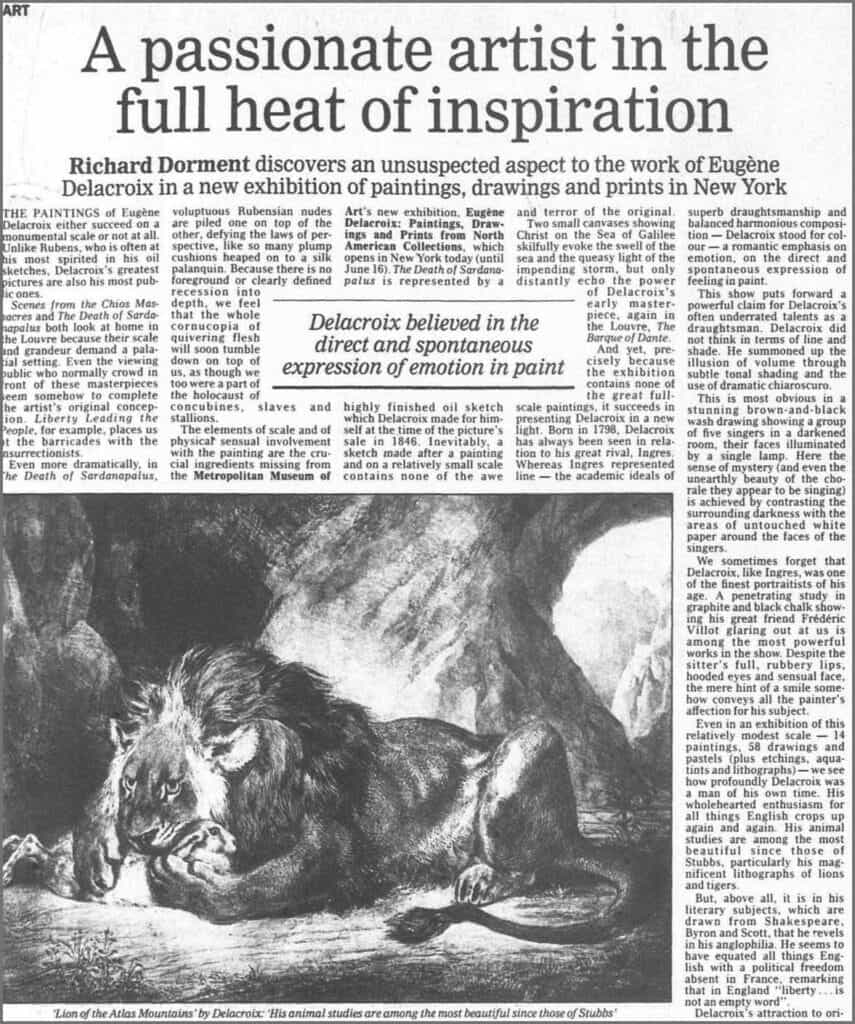

Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix famously depicted the revolution in his work Liberty Leading the People in which an allegorical goddess-figure leads a crowd from smoke and clouds holding high the French flag. One source when reflecting on Delacroix’s work notes how his work was shaped by the revolutionary atmosphere in Europe at the time with the headline “A passionate artist in the full heat of inspiration”.

Like Turner’s work, Delacroix also challenged popular neoclassical aesthetics, with scenes full of action and contrasting colours. Romanticism therefore not only drew on political events to inspire work, but in its style embodied a sense of revolution.

Creating a Rural Idyll

At the end of the eighteenth century, Britain specifically began a period of rapid industrialization. The Industrial Revolution began to urbanize the British landscape by moving away from an agrarian economy to one which was powered by factory technologies. While industrialization has often been framed within the context of progression and modernity, Romanticism explored its negative social and economic aspects.

One source which explored the life and works of romantic poet William Blake reveals the impact of his life growing up in London within this period of industrialization. The article from The Independent on Sunday includes the first two stanzas of Blake’s poem ‘London’ published in 1794 which laments on the issues of poverty, poor working conditions, and child exploitation within the city.

Romanticism’s disillusionment with industrialization, as well as the fear and anxiety it had caused, saw many people in this period reflecting on an idealised rural lifestyle. Artist John Constable captured scenes of pastoral life in his landscapes, by drawing inspiration from the Dedham Vale area on the Essex/Suffolk border where the artist lived as a child. Constable’s most notable work ‘The Hay Wain’ (see this blog’s header image), produced in 1821 has been admired by many as it depicts a romanticised version of rural life.

One Daily Mail article analyses the painting by highlighting minute details, such as the distant men in the field holding scythes to manually cut hay, to demonstrate the intricacies of Turner’s work and the process of constructing the rural idyll.

!["Every picture tells a story." Weekend. Daily Mail, 29 July 1995, p. [44]-45.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/daily-mail-border-1024x678.jpg)

The variety of sources and works explored through Gale Primary Sources highlights the essence of Romanticism, as well as the lasting impact the art and literature from this period has had, as it continues to be enjoyed to the present day. Romanticism was a movement much larger than a reaction to the Enlightenment but drew inspiration from the various social and political changes occurring at the end of the eighteenth century. The plethora of material from this period demonstrates how Romanticism encouraged an individual and personal response by romanticists to the changing world around them.

If you enjoyed reading about Romanticism and the Enlightenment, check out these posts:

- An Overview of the Romantic Period using The Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive

- Tracing the Legacy of William Blake with British Literary Manuscripts Online

- ECCO’ing through the Ages: Exploring Reception with Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online

Blog cover image:

The Hay Wain (1821). Oil on canvas, 130.2 × 185.4 cm (51+1⁄4 × 73 in). National Gallery, London, via Wikimedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Constable_-_The_Hay_Wain_(1821).jpg