│By Heather Colley, Doctoral Student at the University of Oxford│

The history of technological development is synonymous with a history of cultural criticism that questions the applications and ramifications of that very tech. The work of Walter Benjamin is perhaps some of the most significant and perennial in the realm of technology criticism; and, in the age of artificial intelligence, some ideas from his seminal “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”1 offer a useful lens into ever-present – and increasing – concerns about relationships between art, authenticity, criticism, and “mechanical production.”

Original and Replica

For Benjamin, mechanical production meant film and photography. At his time of writing, these mediums represented unprecedented ruptures between artistic practice and artistic commodification, original work and reproductions of work, and the ritual of creation versus the exhibition of creation. Benjamin looked at the chasm between original and replica, and subsequent replicas-of-replicas, and so on, to articulate new modes of art and representation in a modernist period of mass consumption.

Now, theorizations of film and photography feel anachronistic. But the expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) and its role in humanities criticism and scholarship reverberates in the voice of Benjamin’s concerns about the production of meaningful content. “The presence of the original,” he writes, “is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity.” The same can be said in an unprecedented time of machine-generated prose and analysis, in which source text and physical archives are, perhaps, more important to academic integrity and criticism than ever.

Machine-Generated Information and the Humanities

In an environment of unprecedented access to machine-generated information – much of which is “novel-looking,” to use the pointed phrase of Doctors Noam Chomsky, Ian Roberts, and Jeffrey Wattumull – true academic integrity and discernment is increasingly rooted in source text. The flaws of open-access AI (in modes like ChatGPT or Google Bard) for humanities-based criticism and scholarship are rooted in its proclivities for memorization.

Machine-generated knowledge systems memorize and compute – for Chomsky, Roberts, and Wattumull, they predict and conjecture based on masses of information – but they cannot offer creative criticism or causal mechanisms. They lack the self-aware sentience that is a prerequisite to error correction – which is necessary for rational thought. In academic thinking, in which rationality is based on argumentative reasoning that is rooted in creative and often interpretive criticism, the process of self-correction is integral.

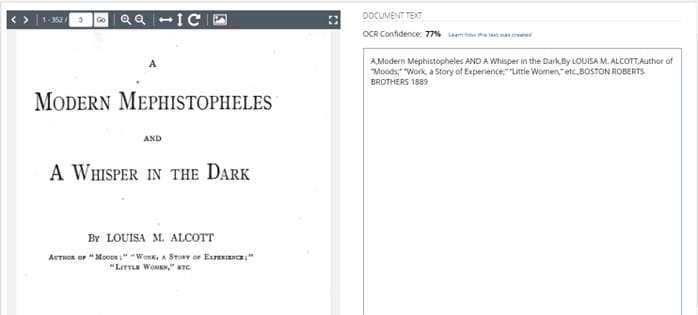

In this unself-aware world of “brute correlations among data points”, as described by Chomsky et al. in their recent New York Times article, the archive emerges as a critical necessity. In eschewing deference to physical source texts there arises a capacity for information – and misinformation – to build upon and legitimize itself within the seemingly infinite world of open-access content. Physical archives can help to rectify errors in Optical Character Recognition (OCR) computational text mining that is especially prone to inaccuracies when mining multilingual texts, texts with distinct typography, or archives which show signs of age including page damage or smeared ink.

Digitization in Contemporary Applications

Of course, machine-generated knowledge is only as complete as the knowledge that we feed it. Archival investigation and re-investigation constantly change our understanding of literary history and culture. The digital humanities – broadly, the scholarly movement at the intersections of digitization and humanities research – is in part about remote and digital access. But rates of digitizing critical source text – and, further, the translation of digitized archival-based material to the glut of machine-based data knowledge – can’t yet match the pace of human archival work.

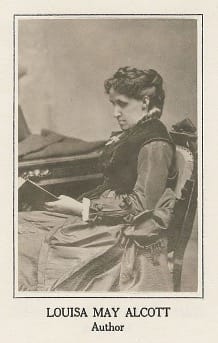

Earlier this month, a researcher used a combination of digital and physical archives to unearth around twelve works of literature by Louisa May Alcott, which were previously unattributed to the American feminist writer. Because Alcott worked across genres and used a variety of pseudonyms – her iconic Little Women is barely representative of her literary oeuvre, which spanned gothics, thrillers, and adult revenge fantasies – the project of unearthing her corpus is complex and discursive.

The story of Max Chapnick’s discovery is representative of the relationship between the digital humanities and the physical archive. Chapnick’s hunt began when he identified fiction under pseudonyms which, he suspected, may have been Alcott’s. The expansive digital collections of the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) and the Boston Public Library enabled him to draw connections between certain texts and Alcott’s style and personal life. But an earlier error in the digitization process stulted confirmation: “He originally searched for I.H. Gould, since the digitized version of “The Phantom” had a wrinkle folded over the page that masked the first initial,” Cody Mello-Klein wrote in their article on the discovery. “Fortunately, Elizabeth Pope, curator of books and digitized collections at AAS, found the original document and confirmed the writer’s name as E.H. Gould.”

The Machine and the Archive

The human process of digitization is susceptible to error; in this case, it affects our understanding of a literary legend, her creative practice, and her publication process. But the preservation of the physical archive also means that such errors can be self-corrected; we can amend our inevitable mistakes, and our self-corrections can contribute to logical humanistic interpretations. The chasm remains, however, between the machine and the archive. When, and how, will machine-generated knowledge incorporate this archive-based hypothesis surrounding a key American author? How will a lack of timely incorporation of the knowledge that Alcott wrote “The Phantom” – a feminist take on Dicken’s A Christmas Carol – affect the type of knowledge that ChatGPT may regurgitate about the author?

The Importance of the Physical Archive

In better understanding and contextualizing discrepancies between the original archive, the (re)produced digital archive, and the machinated knowledge of AI, we might reorient ourselves around the physical archive, defer to it for academic and research integrity. Or, to reference Benjamin again, we might better prevent machinated knowledge from overpowering the archive; because to “pry an object from its shell, to destroy its aura,” might be, in our contexts, to erroneously allow artificial knowledge to legitimize itself over archive-rooted, self-corrected, and logical interpretation.

Blog post cover image citation: Rise of the machines. (May 9th-15th 2015). Economist, 19+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/OXUCSW340676990/ECON?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-ECON&xid=67c25641

If you enjoyed reading about the literary archive in the artificial intelligence era, check out these posts:

- Using Literary Sources to Research Late Nineteenth-Century British Feminism

- Exploring Reception with Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online

- Top 10 Tips for Researching with British Literary Manuscripts Online