|By Lola Hylander, Gale Ambassador at University College London|

Four years ago, when I began studying History and Politics of the Americas at University College London, I had little prior knowledge about the region of Latin America and the Caribbean. I’d studied History A-Level in the UK, but the syllabus focused mainly on European revolutions. My knowledge of Latin America and the Caribbean was limited to the perspective of Europe. For example, I had studied Napoleon III’s attempt to colonise Mexico, but from the perspective of France.

Joining the Institute of the Americas was, therefore, a big adjustment. I had to free myself from the Eurocentric framework I had developed in school. Using primary sources helped me familiarise myself with the region, and students of the region should check out Gale’s Archives of Latin American and Caribbean History, Sixteenth to Twentieth Century database to do so. I found some engaging sources in the Latin American and Iberian Biographies collection on three of the most significant liberators of Latin America and the Caribbean, and these men’s stories can teach us useful lessons about studying the Americas.

© Luis Marden/National Geographic Society/Corbis (selected collection image on Gale platform).

Símon Bolívar

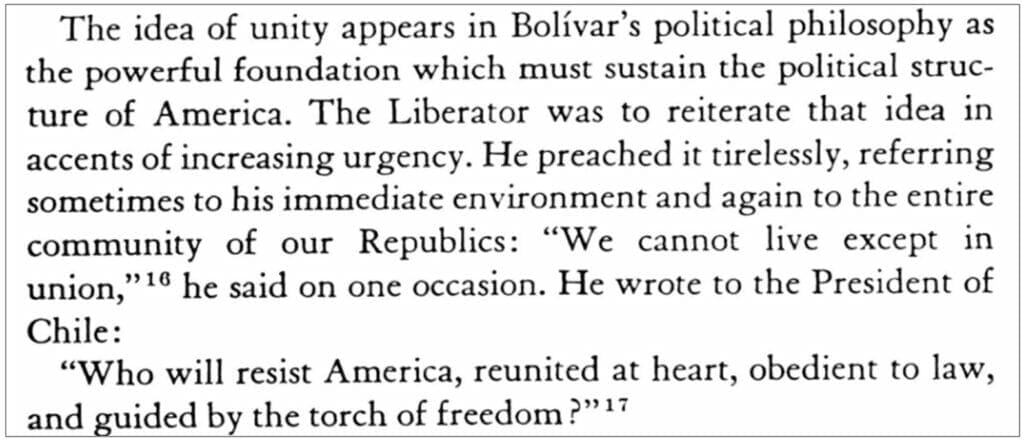

Bolívar was a military leader known as El Libertador throughout Latin America due to his role in freeing Colombia (1810), Venezuela (1813), Ecuador (1822), Peru (1824), and Bolivia (1825) from Spanish colonial rule. One source refers to him as an ‘invincible warrior’ and in another, an ex-president of Venezuela describes how Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador would not have achieved independence had it not been for the ‘seemingly impossible and brilliant feat of his famous march across the Grenadine Andes.’

An important lesson that we can learn from the representation in Gale Primary Sources of Bolívar’s military successes is that the terms ‘America’ and ‘American’ have different meanings in the academia of the Americas. When you hear the term ‘American hero,’ you likely picture George Washington, Harriet Tubman, or the firefighters and police who evacuated the World Trade Center on 9/11. ‘America,’ in the eyes of many, refers to the United States.

However, in the study of the Americas, ‘America’ refers to the region as a whole. In one source, the Venezuelan Minister of Foreign Relations describes how ‘Bolívar belongs to America and his name is proclaimed with pride throughout the new world,’ highlighting the need to broaden our understanding of the term ‘American’ when studying the region. Indeed, while he was a Venezuelan national, Bolívar is considered the father of pan-Americanism as he realised a common struggle between the different Spanish colonies and proposed a unified solution.

The source ‘honours one whom Venezuela cannot consider solely her own,’ as Bolívar was an intra-continental American hero who laid the foundations for further cooperation in a post-colonial world.

José de San Martín

San Martín was an Argentine general who fought alongside Bolívar in the Latin American freedom struggle. He is credited with the liberation of Argentina (1816), Chile (1818) and Peru (1824).

Another celebrated libertador, a stunning songbook dedicated to San Martín that I found in the Gale archive remembers his military prowess in proclaiming:

¡San Martín, el obrero de la espada!

¡Tu empress es de justicia!

¡Nuestra voz te acompaña!

This translates as:

San Martín, the worker of the sword!

Your company is justice!

Our voice accompanies you!

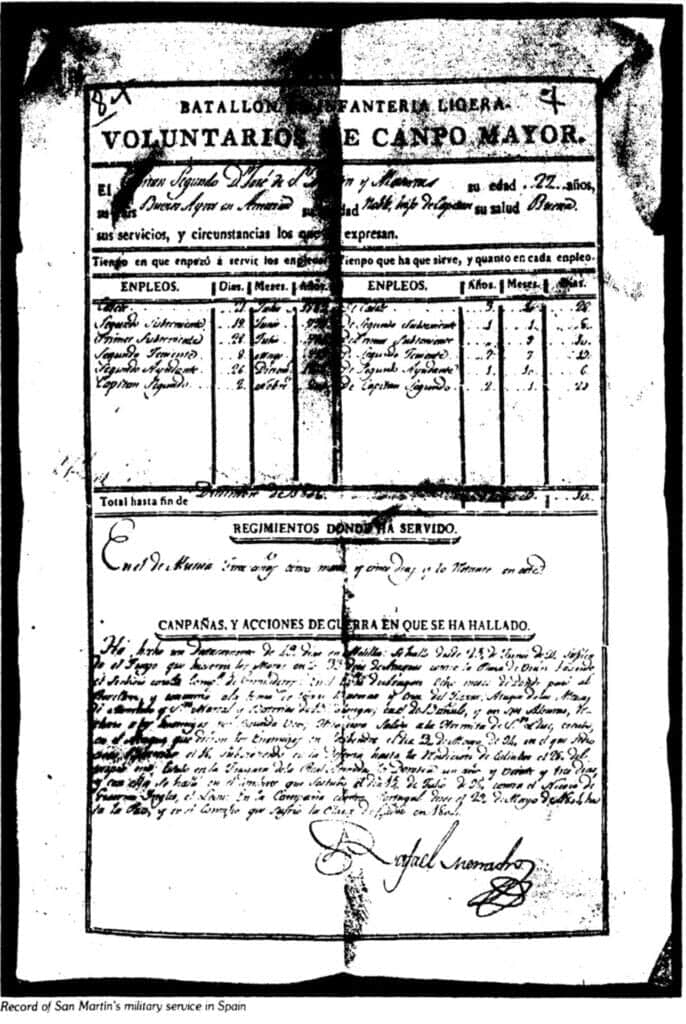

San Martín’s life demonstrates the intertwinement between a colony and its mother country. While born in Yapeyú, Argentina, San Martín’s family moved to Spain when he was six, and one source notes that he joined the Spanish Army as a cadet, aged 11. He trained for 20 years in the Regiment of Murcia under Spain’s leading military generals, and eventually became a colonel for the Spanish army, and fought for them in the Peninsular War against France.

It seems idiosyncratic that San Martín fought both for and against the mother country, and there is extensive scholarly debate attempting to explain his metamorphosis. However, this is an important observation in the study of the Americas, and liberation struggles more broadly. Unlike what Audre Lorde said about how ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,’ San Martín demonstrated that Spanish-learned military skills and strategy could be used against the very state that had trained him.

Toussaint Louverture

The most prominent figure of the Haitian Revolution, Louverture, led the world’s first successful slave insurrection that not only emancipated Saint-Domingue’s slaves, but liberated the colony from French rule. Saint-Domingue (the colony that became modern-day Haiti) was considered the ‘jewel’ of the French West Indies, responsible for most of the world’s sugar exports.

Born a slave, Louverture was freed between 1772 and 1776 (the exact date is unknown) and became a member of the gens de couleur libres – free people of colour – group that were responsible for early Haitian nationalism. Like San Martín, Louverture fought at times for his mother country against the Spanish; an alliance that led to the Sonthonax Proclamation in 1793 that emancipated Saint-Domingue’s slaves. Once emancipated, in a watershed denouement, Louverture turned against the French in war. Although he died before the end of the war, he laid the foundations for his successor, Jean-Jacque Dessalines, to proclaim the independence of modern-day Haiti.

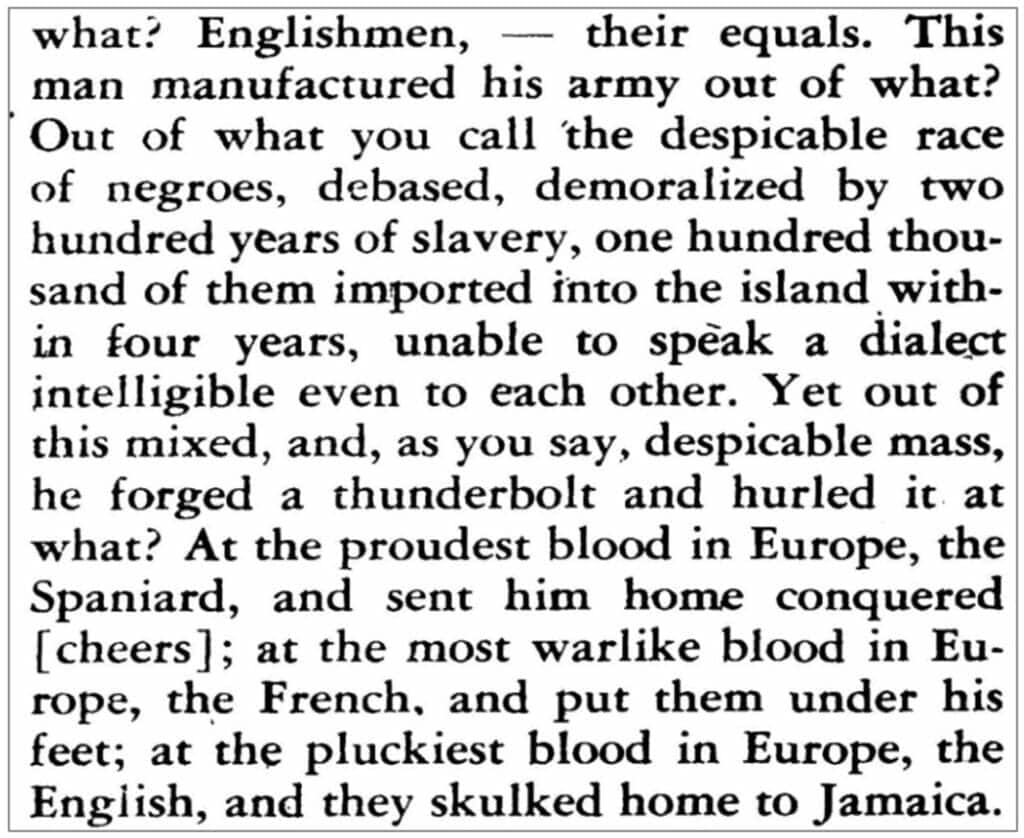

The source below emotively describes his overwhelming role in empowering the black race to overcome European rule.

In the study of the Americas, the Haitian Revolution teaches us that revolutions do not exist in a vacuum; simultaneously, the French Revolution was in full force across the Atlantic. Louverture masterfully drew upon the French revolutionary ideas of liberté, égalité and fraternité to spark nationalist revolutionary spirit in the Saint-Dominguans; the source above notes how ‘Paris had christened Toussaint, the Black Napoleon.’ Indeed, all the aforementioned revolutions highlight the interconnectivity of separate revolutions. The Haitian Revolution was inspired by the French Revolution, and it inspired further slave insurrections in the Caribbean and United States.

Primary Sources Provide a Rich Framework for Studying Unfamiliar Regions

Primary sources have been pivotal to my study of History and Politics, and students researching an unfamiliar region should be sure to dive into Gale Primary Sources to familiarise themselves with a new framework for study. Students of the Americas must check out Gale’s brilliant Archive of Latin American and Caribbean History, Sixteenth to Twentieth Century, which has been updated with an enhanced browsing experience and new and efficient basic and advanced search capabilities to maximise your studies!

If you enjoyed reading about the American liberation struggle, or seek further examples of decolonising the curriculum, check out:

- How Slave Narratives Give Voice to the Enslaved

- Indentured Indian Workers and Anti-Colonial Resistance in the British Empire

- The road to American Independence

- Tiradentes in Brazilian and Portuguese History and Culture: The Oliveira Lima Library

- Unearthing and Decolonising the Rasta Voice

- Discovering New Points of View about European and Colonised Women Using Gale’s Voice and Vision archive

Blog post cover image citation : Meurs, Jacob van (1650), The Most Recent and Most Accurate Description of all of America, available on Wikimedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Most_Recent_and_Most_Accurate_Description_of_All_of_America_WDL172.png