│By Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull, Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford│

As an archival scholar trying to write a PhD thesis in a pandemic, COVID-19 has had a huge impact on my working life. The closure of archives, museums, and libraries during the lockdowns prevented me and many others from accessing essential primary resources needed for doctoral research. And without physical access to exciting objects, manuscripts, and printed items to help bring texts alive, inspiring undergraduate students whilst teaching them over Microsoft Teams became equally difficult. With COVID cases once again climbing, we are far from being free of the pandemic. But how can we try to minimise the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on higher education and research? And what will the long-term impacts of the pandemic be?

Left to right: image by Tim Gouw on Unsplash.com; image by Chris Montgomery on Unsplash.com; image by Ivan Samkov on Pexels.com.

Let’s Get Digital: Researching with Eighteenth Century Collections Online

One way of limiting the impact of the pandemic on research is, rather unsurprisingly in the age of Zoom, improving your digital research skills. Scholars of the long eighteenth century know how important Parts I and II of Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO) are to conducting any piece of research. But when access to research libraries and their talented teams of reading room staff stopped overnight, resources like ECCO that provide high-quality digital surrogates became all the more vital to planning and undertaking research. Nothing can fully replace the experience of holding, examining, and smelling the history in your hands when consulting printed material. But with over 180,000 printed titles and more than 32 million pages at your fingertips, made full-text searchable through Optical Character Recognition (OCR), it really is an unparalleled resource.

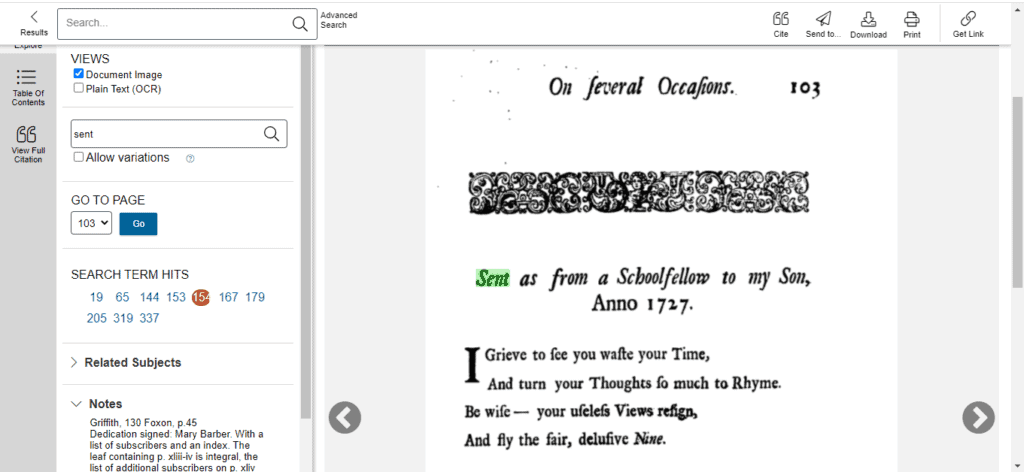

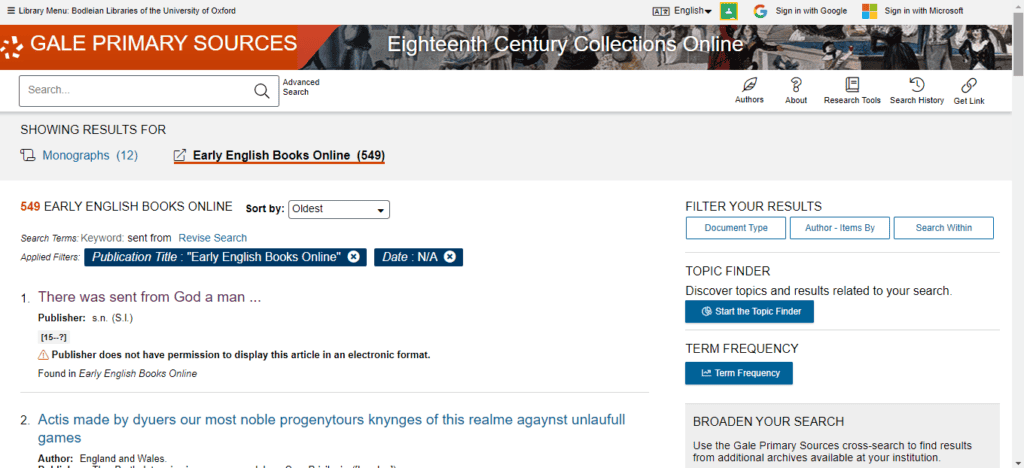

When researching women’s poetry during the lockdowns this became increasingly important to me. As someone who describes themselves as a digital humanist, I’m pretty literate when it comes to using online resources. But in the before times, I’d still often start work on a thesis chapter by sitting with a collection of printed catalogues in the library, using them to select any of the (often unique) items of interest from the stacks. With this no longer an option, I had to up my game when it came to locating primary digital resources using effective search terms. With nearly every printed poetic miscellany published in the eighteenth century accessible to me through ECCO, finding the texts I was interested in (and some important works I didn’t even know existed) was made so much quicker. As a student working on material from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, based at an institution that also has access to ProQuest’s Early English Books Online (EBBO), the revelation of the EEBO/ECCO cross search tool has made researching and teaching across period boundaries infinitely easier. Learning to use and edit the surprisingly accurate OCR generated texts for each document has also saved me valuable time transcribing “gobbets” into my lesson plans and thesis notes.

Barber, Mary. Poems on several occasions. Printed for C. Rivington, at the Bible and Crown in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, M.DCC.XXXIV. [1734]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0112275057/ECCO?u=oxford&sid=bookmarkECCO&xid=0aeb5ab4&pg=154

![Barber, Mary. Poems on several occasions. Printed for C. Rivington, at the Bible and Crown in St. Paul's Church-Yard, M.DCC.XXXIV. [1734]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Image-3-1024x466.png)

Barber, Mary. Poems on several occasions. Printed for C. Rivington, at the Bible and Crown in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, M.DCC.XXXIV. [1734]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0112275057/ECCO?u=oxford&sid=bookmarkECCO&xid=0aeb5ab4&pg=154

Teaching with Digital Collections: British Literary Manuscripts Online: 1660-1900

Digital collections have also become increasingly important in teaching during the pandemic. I usually begin a term of teaching by taking my undergraduates into the archives. The chance to handle original manuscripts and early printed editions alongside one another is always a highlight for them and really gets them excited about the material we’ll be studying. When this couldn’t happen last year, I had to get creative. I’ve always taught the basics of ECCO to help students navigate the rich world of eighteenth-century print in their essays. But I now also had to think how I could introduce them to manuscript culture using only digital resources. Learning that my university had access to British Literary Manuscripts Online: 1660-1900 provided me with the solution. By encouraging students to explore the digitised manuscript of Jonathan Swift’s Memoirs Relating to the Change Which Happened in the Queen’s Ministry in 1710 available in British Literary Manuscripts Online, and asking them to compare it with later printed editions available through ECCO, I was able to introduce them to the basics of manuscript circulation, authorial revisions, and textual transmission whilst also improving their digital literacy skills.

![Jonathan Swift, 'Draught of Memoirs' [relating to the change which happened in the Queen's Ministry in 1710], London, National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum, F.48.G.6/3, fol.1r. British Literary Manuscripts Online.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Image-4-1.jpg)

The Long-Term Impact of the Pandemic on Teaching and Research

The pandemic may have forced PhD students to refine their expertise in researching and teaching with digital primary sources. But with an ever-increasing pressure on the humanities to embrace the digital, the long-term impact of creating a generation of tech-savvy PhD students and undergraduates with an increased range of transferrable skills in a difficult job market (academic and otherwise) can only be beneficial. Online and hybrid teaching is becoming an increasingly common way to deliver teaching in higher education even after the end of social distancing measures. Gaining the skills to design and deliver this form of distance learning, as we all learnt in the first months of the pandemic, is no easy feat. For those who do manage to get jobs in the education sector, this will serve them well in the ever-changing landscape of higher education.

If you enjoyed learning more about how the student and PhD experience has been impacted by the pandemic, you may like:

- Pandemic Perspectives – Interview with Madi, student at National University of Ireland, Galway

- The Impact of the Pandemic on Students at the University of Johannesburg

- The University Experience – Before, During and After the Pandemic

For more teaching and research tips from a PhD student, try:

For more tips and tricks to using primary sources in your studies, check out:

- Using Primary Sources in Revision and Exam Preparation

- How To Handle Primary Source Archives – University Lecturer’s Top Tips

Blog post cover image citation: Anon, Some Observations Concerning the Plague: Occasioned By, and With Some Reference to the Late Ingenious Discourse of the Learned Dr. Mead, Concerning Pestilential Contagion, and the Methods to Prevent It (Dublin: George Grierson, 1721), Eighteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0109611968/ECCO?u=oxford&sid=bookmarkECCO&xid=b85f807b&pg=1