│By Dr Lucy Dow, Gale Content Researcher│

Once again this year, the Notting Hill Carnival was sadly cancelled due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. In this blog post I will explore the life of Claudia Jones, often credited with starting the Notting Hill Carnival. Using Gale Primary Sources, I will look at what was written by and about Jones during her lifetime, and how she is remembered.

Image available on Wikimedia.

“Mother of Notting Hill Carnival”

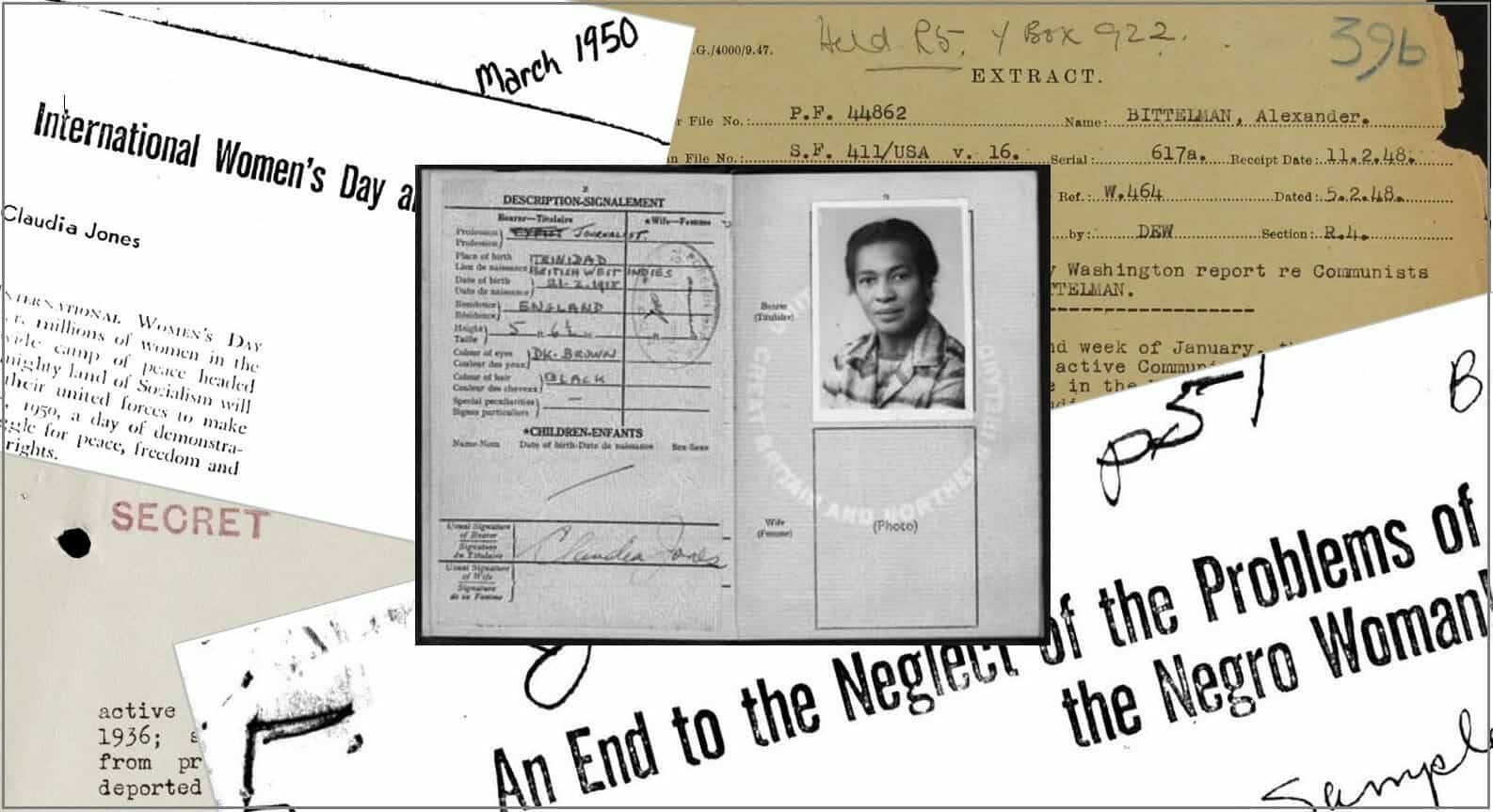

Using the Gale Primary Sources cross-search tool to search for references to Claudia Jones across all of the Gale Primary Sources archives produces a number of late twentieth and early twenty-first century newspaper articles that describe Claudia Jones’ role in starting the Notting Hill Carnival. The article below from the British newspaper, The Independent, in 2010, now found in The Independent Historical Archive, which describes her as “mother of Notting Hill Carnival,” is a perfect example:

Deported for her Communist Politics

The article highlights Jones’ connection to the Caribbean and the Caribbean community living in London in the mid-twentieth century. However, Jones’ journey to Britain was somewhat different to many of the other people of Caribbean-origin living in Britain in this period.

In the aftermath of the Second World War the British government encouraged people from across the British Empire to move to Britain to help the “mother country” rebuild; the generation of Caribbean people who responded to this request for help would come to be known as “the Windrush generation,” named after the boat, the Empire Windrush which arrived in Tilbury docks, near London, from Jamaica in 1948. Jones, however, was deported to Britain from the United States because of her Communist politics.

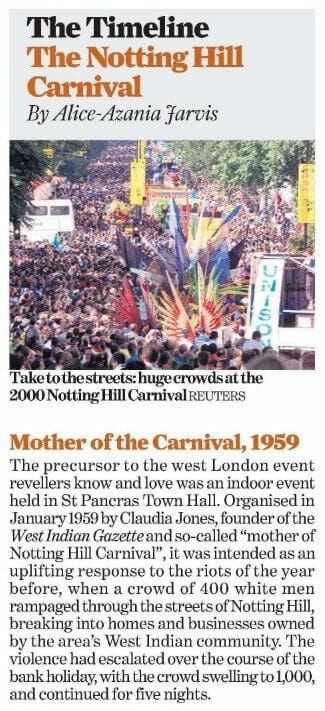

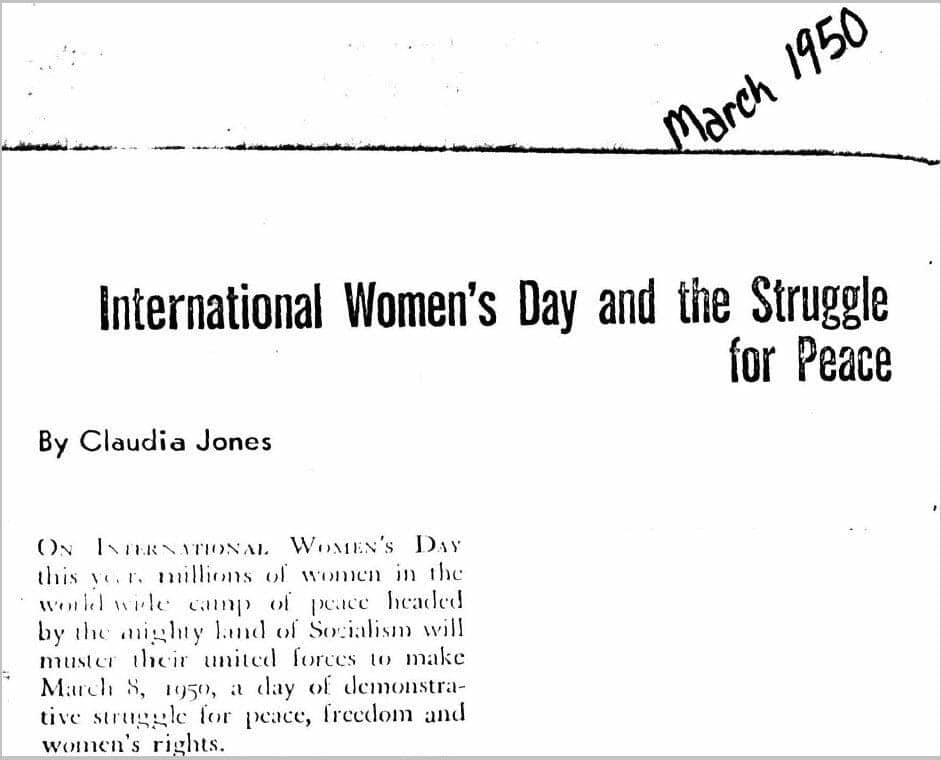

As this British Security Service file from Gale’s Political Extremism and Radicalism archive notes, Jones was arrested in the United States in January 1948:

As this source goes on to explain, Jones’ arrest was part of a deliberate attempt by the US government to harass the Communist Party of the United States. Her deportation was contested by the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born (described in this intelligence report as a Communist front organisation) and she was not immediately deported from the United States.

Charged Under the Alien Registration Act

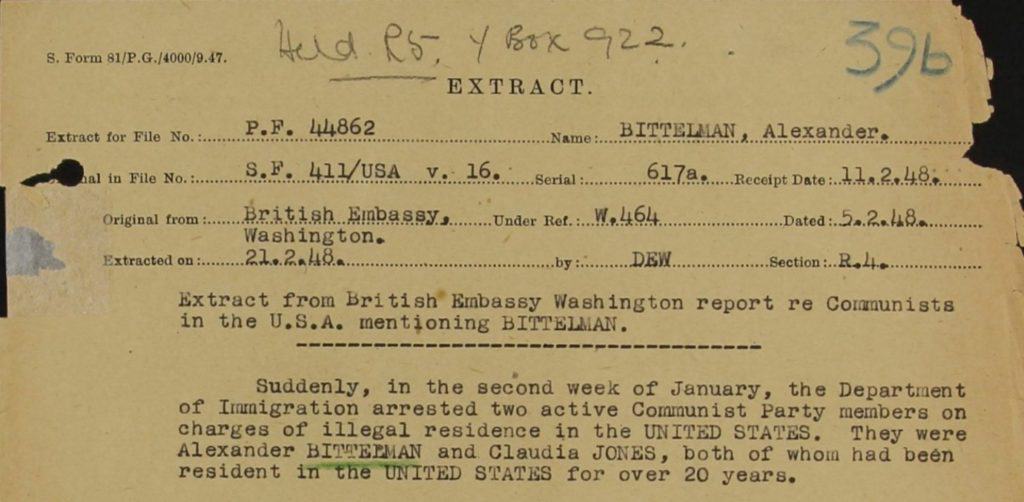

In 1951 she was charged under the Smith Act, otherwise known as the Alien Registration Act, which required non-citizens resident in the United States to register with the federal government and which applied criminal convictions to those promoting the violent overthrow of the U.S. government.

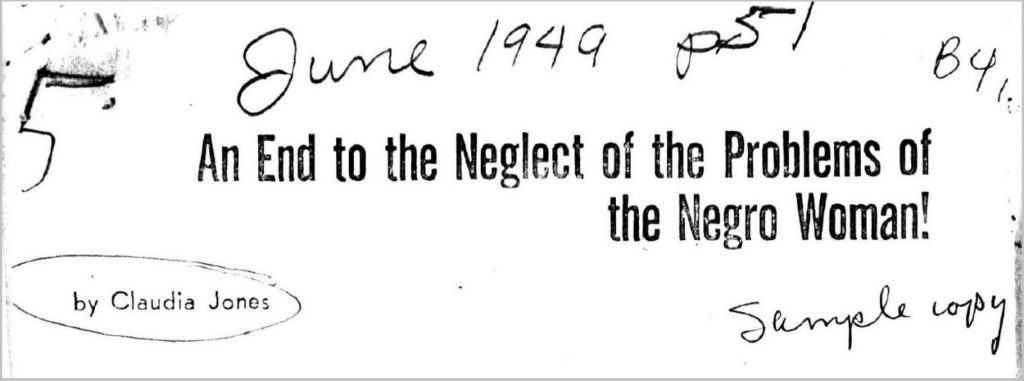

In 1953 she was tried and convicted based on an article she had written on International Women’s Day in 1950 which can be found, in full, in Gale’s Women’s Studies Archive:

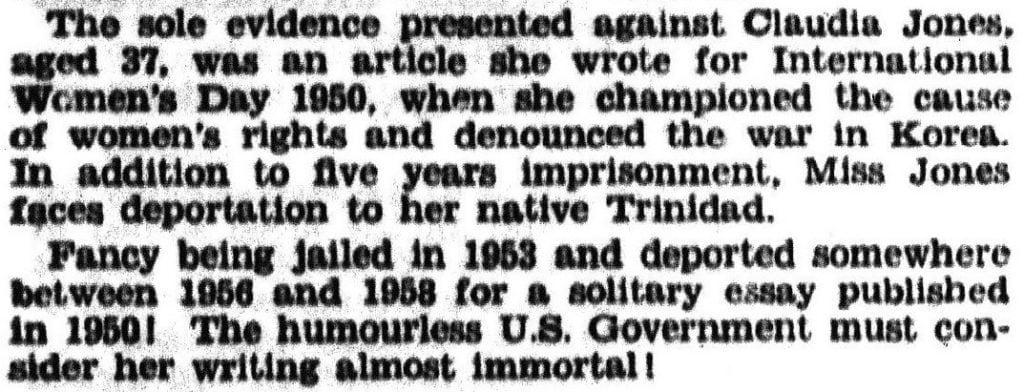

Her arrest, trial, incarceration, and deportation by the US government based on one article was satirised in this account from the Glasgow-based Anarchist periodical The Word:

This item is from the Papers of Guy Aldred which were included in the Religion, Society, Spirituality and Reform module of Nineteenth Century Collections Online. His papers spanned from the end of the nineteenth century to mid-twentieth century. The Papers of Guy Aldred were considered important for the module, so it was decided not to exclude the later parts of his collection.

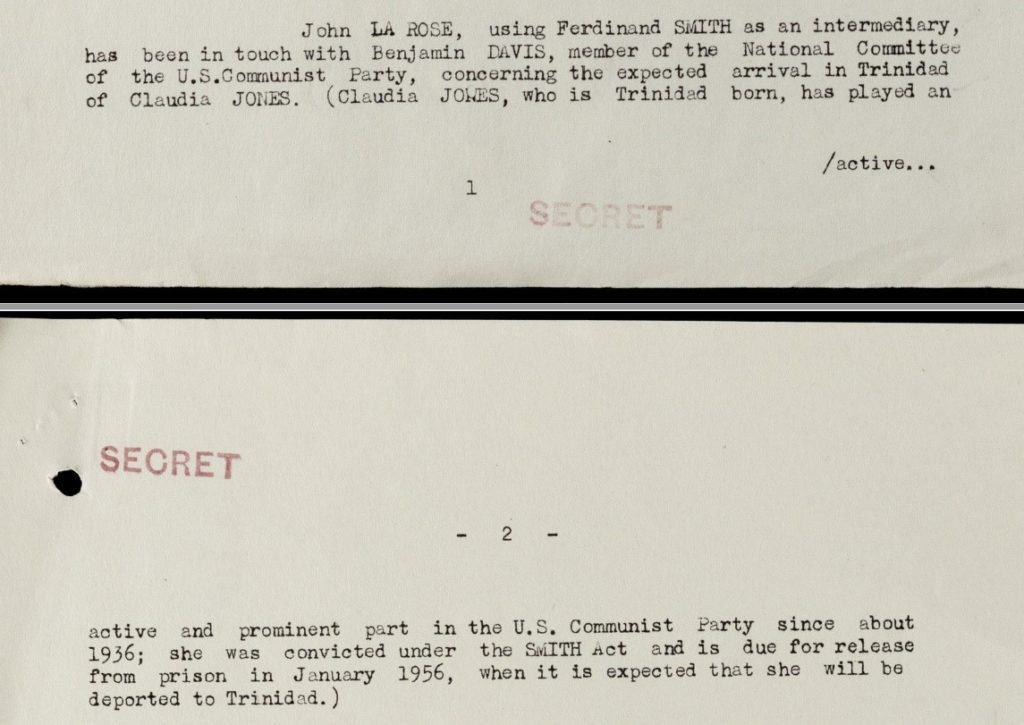

Potential Deportation to Trinidad

Her release from prison, and potential return to Trinidad (the place of her birth), in 1955 was of concern to the British colonial government in Trinidad at the time who were tracking the activities of Communists and other pro-independence activists throughout the British West Indies (as they were then known). Gale’s Declassified Documents Online: Twentieth-Century British Intelligence archive contains this Colonial Intelligence Summary from 1955, in which there is discussion of John La Rose’s (and other Trinidadian activists’) preparations for Jones’ release and return to Trinidad:

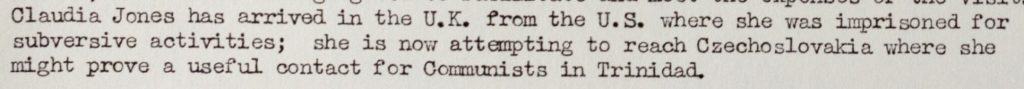

Deportation to the UK

Such was the concern over the potential impact of Jones’ return to Trinidad that she was instead, as a British subject, deported to the UK. According to the December 1955 intelligence report below she was aiming to reach Czechoslovakia “where she might prove a useful contact for Communists in Trinidad”.

An Active Member of the Communist Party of Great Britain

However, her passport was withheld by the British government and she remained in London where she remained an active member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, became a key figure in early post-war anti-racist activism and set up the West Indian Gazette, Britain’s first major black newspaper.

Jones’ activities in the United States and Britain reveal her commitment to Communism and her deep engagement with political action and thought. Her 1949 article “An End to the Neglect of the Negro Woman!” has been described as a manifesto for intersectional feminism before the idea of “intersectionality” had been created. In light of her political beliefs, her writing on a variety of subjects, and the interest she elicited from both the US and British security services, it is worth asking why she is now best known, in Britain at least, for being the “mother of Notting Hill Carnival”.

Complex Political Beliefs

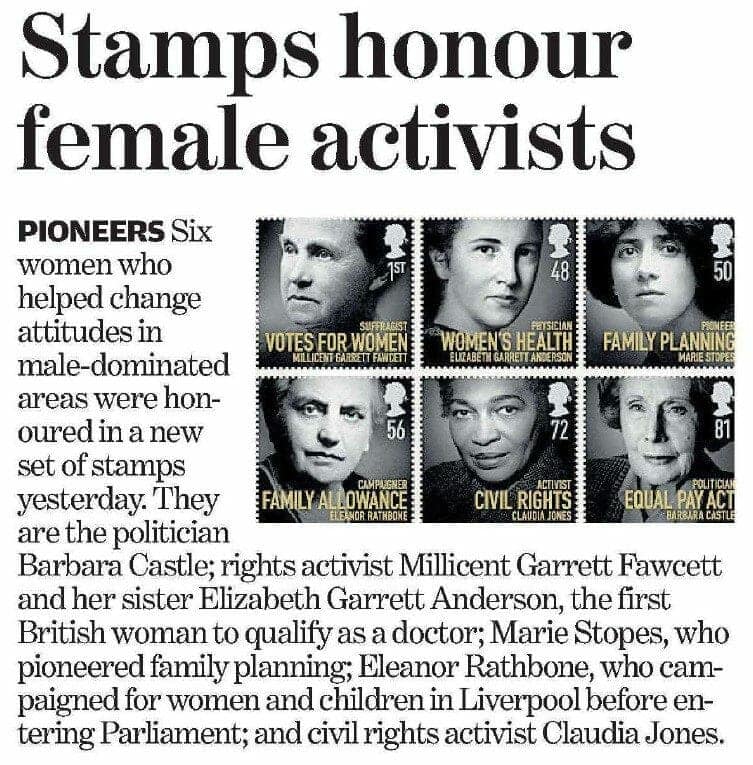

This 2008 stamp collection describes Jones as a “civil rights activist”, a very simplified version of the life revealed above. The digitised primary source material available from Gale has allowed us to explore her life experience and better understand her more complex political beliefs. Thus, using Gale Primary Sources we can see the ways in which important figures within mid-century anti-racist and anti-imperialist movements had much more complex political affiliations and ideas than much of the popular narratives about these movements allows for.

To find out more about Claudia Jones, I recommend Carole Boyce Davies’ Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones (2008). You can also visit Boyce Davies’ website here.

If you enjoyed reading about the life and politics of Claudia Jones on The Gale Review, you may enjoy:

- Grassroots activism in amateur publications written by women, African Americans and the LGBT+ community

- The Lesbian Avengers and the Importance of Intersectionality in LGBTQ+ Activism

- Remembering Rosa: When One Word Sparked a Civil Rights Movement

- Decolonising the Curriculum with Archives Unbound

- Miscegenation, or ‘Fake News’ of the Civil War

- Power, Protest & Presidential Profanity: The ‘Race’ for Civil Rights

Or you may like to explore more posts of interest on Civil Rights, Communism or within the Society and Politics category.

Blog post cover image citation: Pages from the British passport of Claudia Jones. Available on Wikimedia Commons.