│By Juha Hemanus, Gale Ambassador at the University of Helsinki│

We’ve all heard references to “fake news” and “alternative truths,” particularly in recent years. There have also been more in-depth analyses of the “post-truth time” and the “end of truth”. Examining the motives of those who generate “fake news” stories – and the motives of those who claim that a story is fake – is fascinating. This intriguing phenomenon also has an interesting past, with countless examples of “fake news” throughout history. Indeed, a previous ambassador at the University of Helsinki, Pauli, explained that fake news has had alternative names in history, such as “erroneous reporting”. In this blog post, I will look a little further into history to consider questions such as: Where did the fake news phenomenon come from? Under what circumstances was it born? What is it intended for and what has been accomplished by false claims about actual events?

The founding of a nation went hand in hand with the development of the press

The emergence of the United States as a nation and an independent state from the 1630s to the 1770s saw many milestones in the field of journalism, which went from pandering to the state, to a more independent press that questioned the state – but had not yet reached a stage of objectivity. First the curtsying and self-censoring follower of central power grew, and then the press developed into something known as the “fourth estate,” a name for a more independent press which allows and encourages political debate. Papers also started allowing the central power policies to be questioned on the basis of party formation and party politics. False or indoctrinating claims were thrown based on party political gain, as still happens today!

An early example of this was James Franklin’s New-England Courant. One of the first newspapers in America, the short-lived New-England Courant was published by James Franklin in Boston from 1721 to 1726. The paper served as the professional springboard of young Benjamin Franklin, James’s brother, reminding us of the importance of journalistic content in serious political developments. The young Benjamin Franklin served as an apprentice, only to leave for Philadelphia in 1723, growing to become one of the founding fathers of the new-born state about 50 years later. We see reference to the New-England Courant in the primary source below found in Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online archive, Works of the late Doctor Benjamin Franklin: consisting of his Life written by himself, together with essays, humorous, moral & literary, chiefly in the manner of The spectator. In two volumes.

There are numerous other examples of “fake news” over the years. For example, the faltering health of King George II was reported in the mid-eighteenth century on the wrong grounds, for political reasons. The New York Sun reported spectacularly of life found on the moon in 1835, and with this claim it quickly gained a bunch of new subscribers until a month later, on a much quieter tone, had to admit the story was a hoax. The rates at the London Stock Exchange were seriously manipulated a couple of times in the early 1880s with fake war news in the hope of quick wins.

Fake news and yellow journalism – accomplices in the crime of distorting facts

A more systematic stretching of the truth began in 1890s New York, with the birth of what came to be labelled “yellow journalism” – sensational news aimed at maximising papers’ sales and circulation. Sensationalising news isn’t exactly the same as fake news but they’re closely aligned and certainly grow out of a similar psychological landscape.

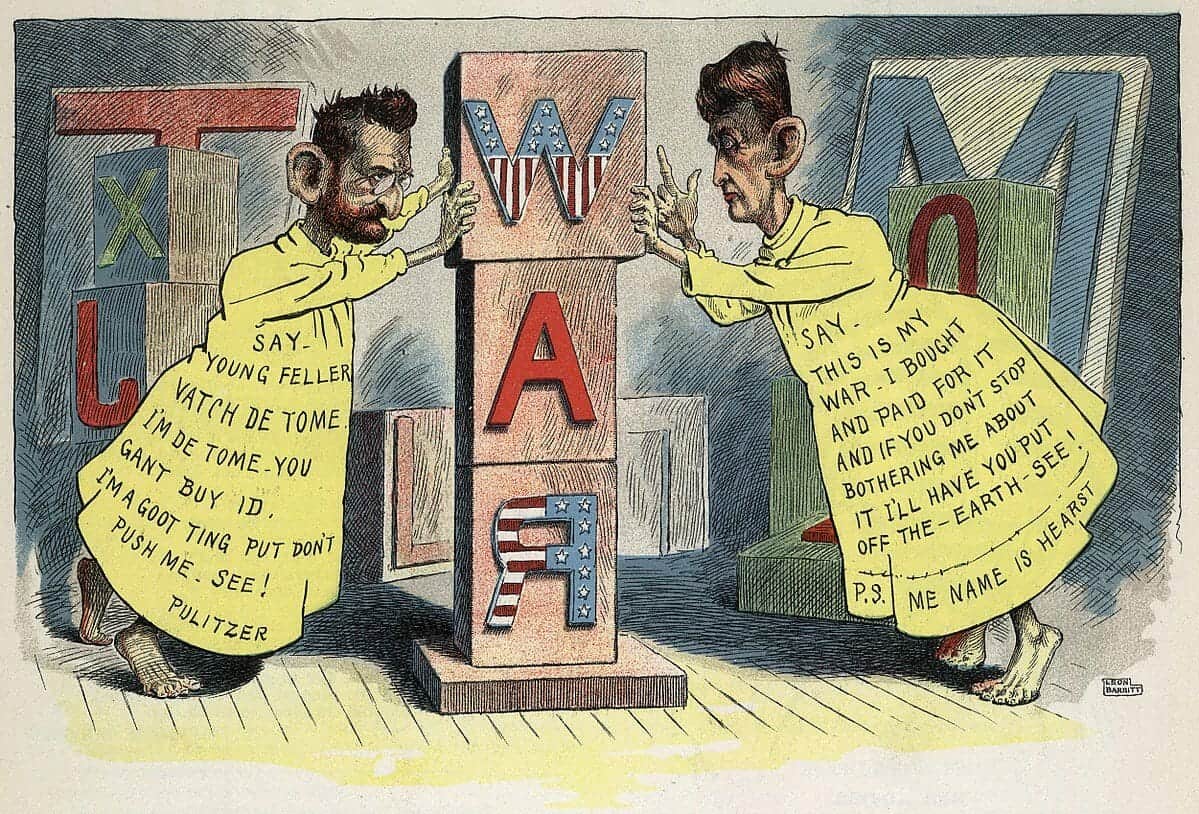

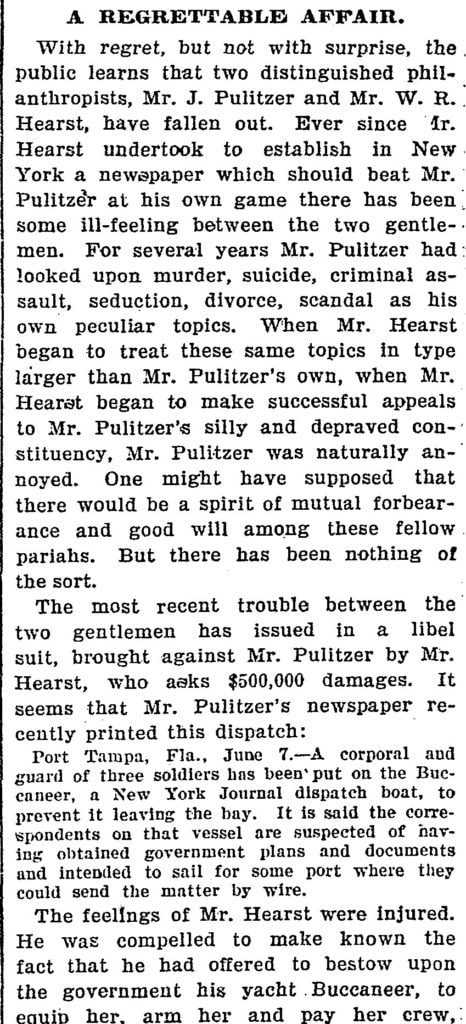

The name “yellow journalism” came from the cartoon character Yellow Kid, who originally appeared in Joseph Pulitzer’s paper, the New York World and became so popular that the New York Journal owner William Randolph Hearst wanted to buy the rights for the Yellow Kid and its artistic creator, and the paper copied the sensationalist style of the New York World. This of course caused a huge uproar. As seen in the primary source below, an article from the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel from June 1898, found in Gale’s Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers digital archive, the gentlemen were not on the most amicable terms with each other!

Notably, the birth of the morally raked “yellow press” took place in an era when the reign of Christianity as an ethical guideline for the press and public opinion in general was faltering, and more dramatic means to sell papers were suddenly considered possible.

Our susceptibility to “fake news” has its roots in human psychology

After exploring some of the many examples of “fake news” over the years, I want to take a deeper dive into the psychology behind the phenomenon – why we believe it, and why it proliferates.

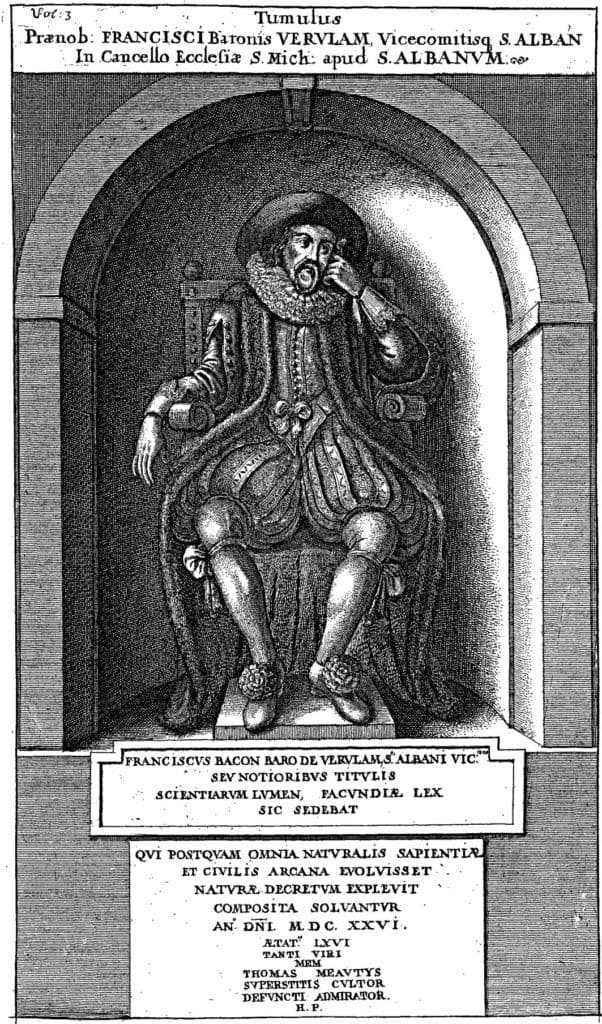

It has its root in human psychology. The earliest explanation of the so-called “confirmation bias” was given by the philosopher Lord Francis Bacon in his masterpiece Novum Organum in 1620. As Bacon explains, the “confirmation bias” is a psychological phenomenon that makes one trust and gather positive content and proof to support one’s pre-adopted opinion and believe it over anything negative that the mind already neglects or despises. It’s psychologically easier to believe material that “support to one’s own theory” over material that contradicts it. Lord Bacon blamed “bad philosophy and science” and “inaccurate language” for this bias. It is hard not to see the relevance of this to the fake news phenomenon in the twenty-first century!

The role of extreme individualism in “fake news”

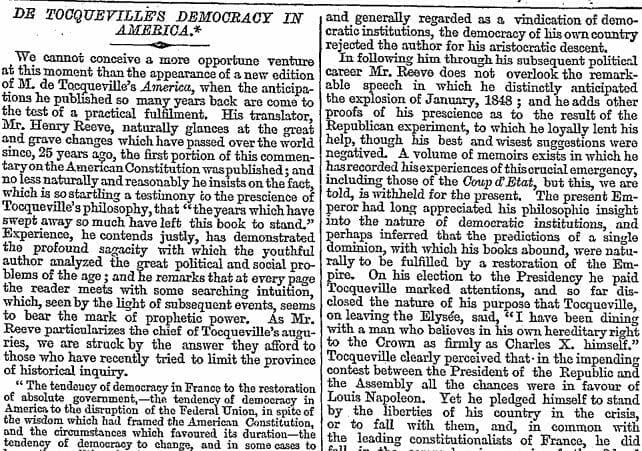

De Tocqueville’s masterpiece Democracy in America (1835) also has some interesting commentary on society’s susceptibility to “fake news”. His observation that “extreme individualism” leads to a situation in which people “withdraw and close themselves inside their own lonely hearts” is a bleak prognosis for a western society where community no longer exists – and a factor in our susceptibility to fake news.

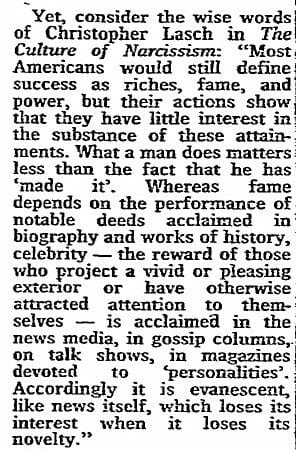

We can add to this discussion the American philosopher Christopher Lasch’s view of the loss of a sense of history and a general fragmentation of the Western worldview which has contributed to shaping a “culture of narcissism” and superficiality, making us prone to accept false claims as “facts” or “real news” (see article below from The Times in June 1981).

Critical analysis helps us avoid the pitfalls of “fake news”

As shown in this blog post, there are many factors which have contributed to the “media bias” seen in the press over the course of its existence. Today’s algorithmic output and manipulation of news is just as likely to be “fake” or entrenched in bias. And in today’s world, there is also the added impact of what are known as “bubbles” or echo chambers of the internet. The year 2016 saw two major elections: the UK Brexit referendum and US presidential election, both of which were surrounded by fake news allegations and accusations.

Further back in modern history we find other examples of inaccurate news – the hasty news coverage of, for example, 9/11, the assassination of JFK, and the sinking of the Titanic. It is worth noting, however, that inaccurate information can be disseminated unintentionally due to the urgent need for news and lack of topical information, rather than the intentional creation of inaccurate news. There are, of course, also many examples of the deliberate dissemination of false information, made in the name of political or financial gain, or pure human interest. And both false news and fake news can be damaging.

The best way to resist fake news is still to critically analyse and familiarise oneself with the original sources of information; check the facts and always consider the issue, argument and claimant. A critical viewer needs to be aware of the context and hear counterarguments, so they can join the dots themselves. All this demands more from journalists and relies on a more critical public but it is our best strength against the proliferation of fake news.

If you enjoyed reading about the history of “fake news” using material from Gale Primary Sources, you might like: