│By Rebecca Bowden, Associate Acquisitions Editor, Gale Primary Sources│

By the end of 2018, the UN reported that an unprecedented 70.8 million people had been forced from their homes by conflict and persecution. Since its start on 15 March 2011, the Syrian Civil War has caused nearly 6.7 million Syrians to become refugees, with another 6.2 million people displaced within Syria. At the same time, the number of refugees from across North Africa increased significantly with the Arab uprisings of 2011. Additional refugee crises arose throughout the 2010s – although there has been little reporting on the subject, such as the over four million Venezuelans who have left their country since 2014. Most recently, there has been the much better covered flight of 900,000 Rohingya to Myanmar. Modern warfare, internecine strife, economic disruption and now climate change have both accelerated the number and exacerbated the breadth of refugee crises, impacting governments and straining international relations.

In many ways, refugee crises are nothing new. They are simply the latest in a long history of mass migration in modern history, as vulnerable populations flee famine, war, political persecution, religious violence and environmental disaster. Two million refugees were displaced by the Great Famine in Ireland in the 1840s; large-scale violence and religious persecution plagued the partition of India in 1947, displacing between ten and twelve million people (according to the census, 2% of India’s population were refugees by 1951); the Korean War triggered significant forced migration, including the famous Hungnam evacuation when the SS Meredith Victory, a U.S. merchant marine ship designed to carry sixty, rescued some 14,000 refugees in a feat that became known as “the Miracle of Christmas”. And then there is the American experience, as refugees who fled by boat from Vietnam, Haiti, and Cuba landed on American shores.

In the twentieth century, the single largest global displacement of people – some sixty million – took place immediately prior to, during, and shortly after World War II. In Forced Migration and World War II, the first part of the new Refugees, Relief and Resettlement series, Gale tells the story of this mass dislocation of people from across Asia, Europe and North Africa by providing scholars with access to a unique collection of primary sources.

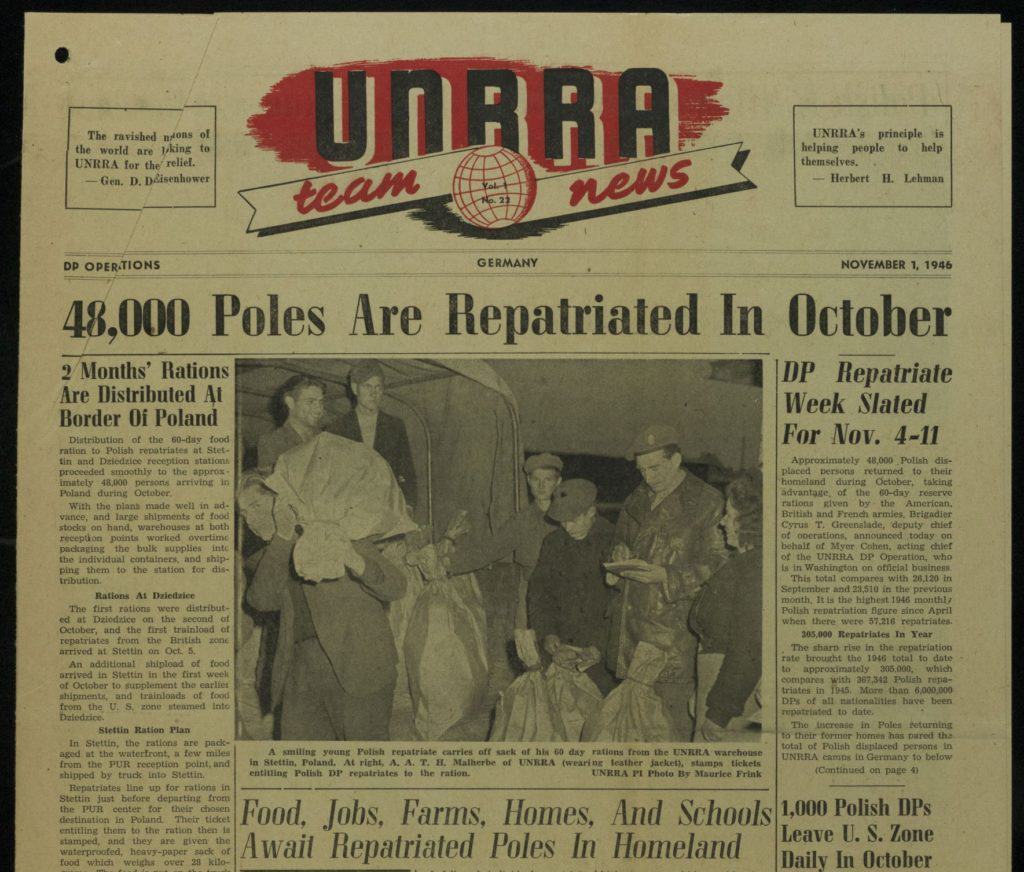

UNRRA: General Policy. 1946-1947. MS Refugee Files from the Records of the Foreign Office, 1938-1950 FO 1052/359. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CHUAPJ906896814/RRRW?u=webdemo&sid=RRRW&xid=69b4a42e

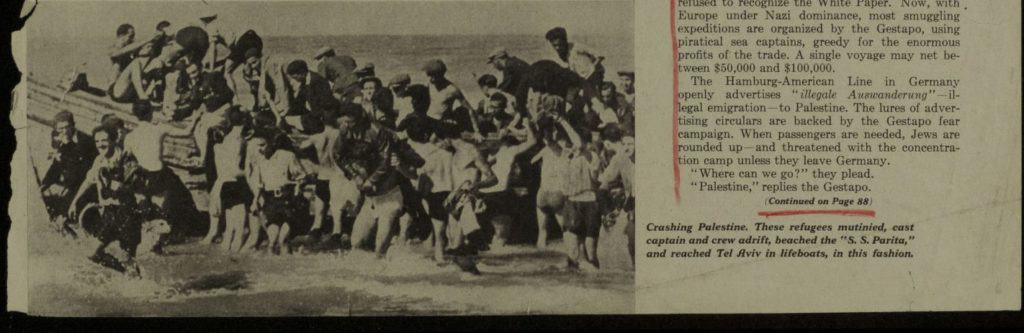

Immigration into Palestine (Illegal). Code 48 File 11 (Papers 3502-6690). 1941. MS Refugee Records from the General Correspondence Files of the Political Departments of the Foreign Office, Record Group 371, 1938-1950 FO 371/29162. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EBITPX697888595/RRRW?u=webdemo&sid=RRRW&xid=d79bf7f1

Humanitarian Raoul Wallenberg

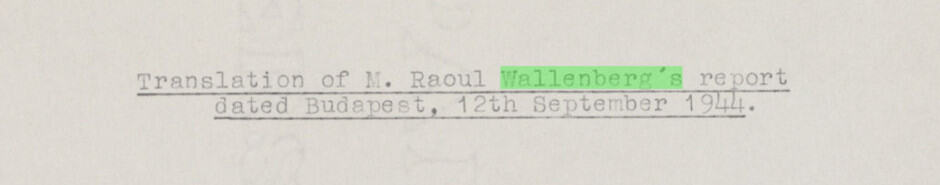

In this blog post we explore the path of one important humanitarian through the archive, chronicling how his work changed the lives of tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews. His name is Raoul Wallenberg. While not a refugee himself, Swedish-born Wallenberg played a key role in rescuing tens of thousands of Jews from Nazi persecution. An architect and a businessman, Wallenberg was recruited by the US War Refugee Board in June 1944. By July he was serving as the Swedish Attaché at the Swedish Legation in Budapest, filing reports and sending information back to unoccupied territory – a number of which now live in the National Archives in the UK. To Wallenberg though, this work was not diplomatic but humanitarian. A telegram from the National Archives and Records Association in the United States reports that:

“…the newly designated attaché, Raoul Wallenberg, feels however that he, in effect, is carrying out a humanitarian mission in [sic] behalf of the War Refugee Board. Consequently he would like full instructions as to the line of activities he is authorized to carry out and assurances of financial support for these activities so that he will be in a position to develop fully all local possibilities.” (View source)

Situation of Jews in Hungary: Efforts to Avert Further Persecution. Code 48 File 3 (Papers 1561 – 1668). 1944. MS Refugee Records from the General Correspondence Files of the Political Departments of the Foreign Office, Record Group 371, 1938-1950 FO 371/42821. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/AMVGYR174146864/RRRW?u=webdemo&sid=RRRW&xid=eba46bbf

This important work is further referenced in committee minutes found in the TNA, where he “asks…for funds because he cannot work without them…for the establishment of camps for about 2,000 Jews, who are under Swedish protection, and for the cost of transporting them.”

It is this humanitarian work, and his successful efforts to rescue Hungarian Jews, that earned him numerous humanitarian honours in the years since the end of the war. He was never able to receive them. His dedication to the cause is highlighted by the following, from the UK’s Foreign Office Files:

“Monsieur Wallenberg also writes that the Red Army is expected in Budapest bout the middle of October and he feels that he must remain at his post at this critical time…believes his mission will be ended as soon as the Russians enter Budapest and he proposes to try and leave the country just before the capital falls. On the other hand, he has expressed himself willing to remain in Budapest after its occupations by the Russians if necessary.”[5]

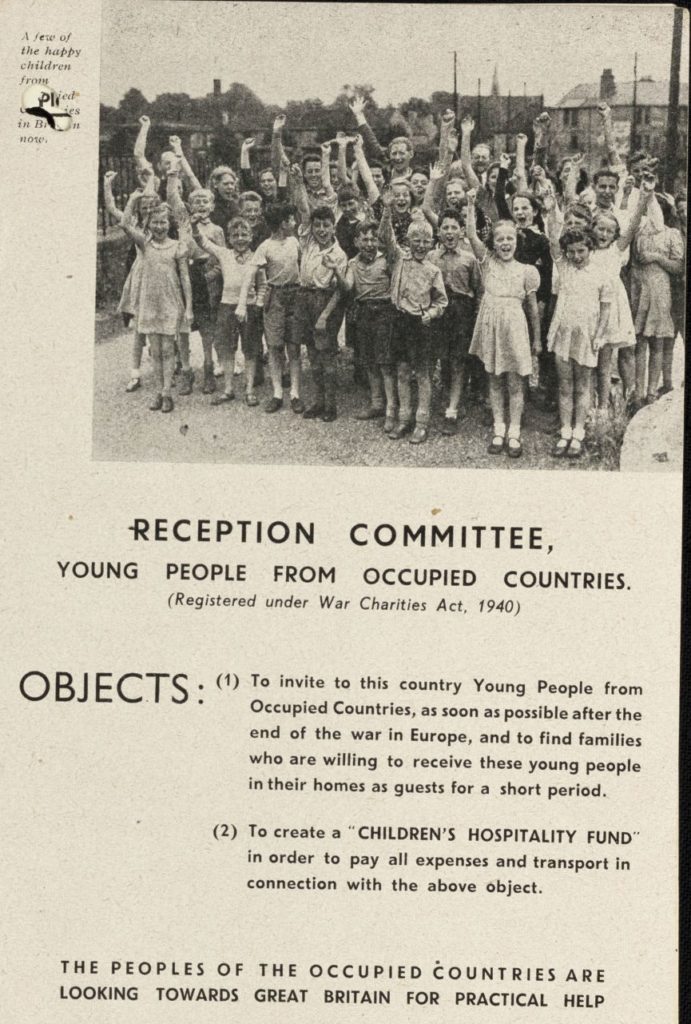

Patronage by Prime Minister of ‘Reception Committee’ Young People from Occupied Countries. 1945. MS Refugee Records from the General Correspondence Files of the Political Departments of the Foreign Office, Record Group 371, 1938-1950 FO_371_51245_WR2933. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/ELIDPJ047371320/RRRW?u=webdemo&sid=RRRW&xid=88245e74

The disappearance of Wallenberg

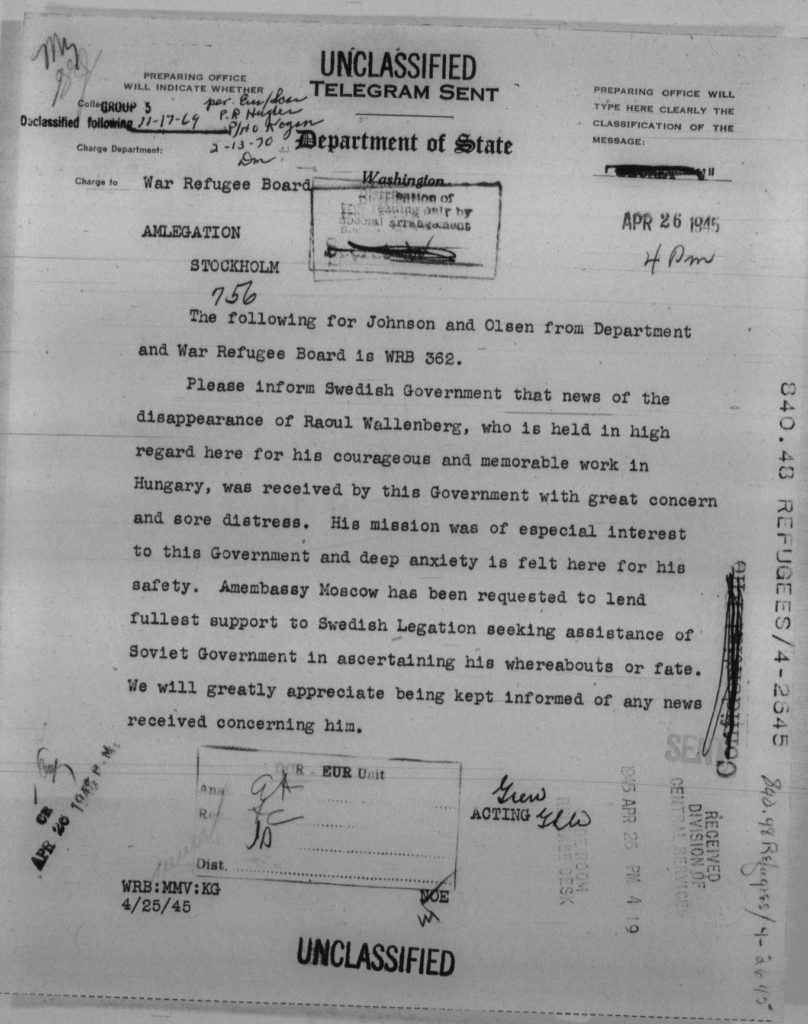

Unfortunately, it was this willingness that led to his undoing. On 26 December 1944, Budapest was encircled by the Red Army in a siege that lasted 50 days and ended with the unconditional surrender of the city on February 13, 1945. It was a strategic victory for the Allies. Sadly for Wallenberg, however, on January 17, 1945 he was detained by the Russians on suspicion of espionage and subsequently disappeared. A Department of State telegram indicates the value that the Allied governments had placed on the work that he was doing, detailing how he “is held in high regard here for his courageous and memorable work” and that the news of his disappearance was “received by [the US] government with great concern and sore distress” with “deep anxiety…felt here for his safety.”

U.S. State Department Records Related to Problems Affecting European Refugees, April 26 1945 File. April 24-26, 1945. TS Records of the Department of State Relating to the Problems of Relief and Refugees in Europe Arising from World War II and Its Aftermath, 1938-1949. National Archives (United States). Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BAZTXR815212588/RRRW?u=webdemo&sid=RRRW&xid=70171566

Wallenberg’s story survives

Raoul Wallenberg was never found, although he is reported to have died in July 1947 while imprisoned by the KGB. The motives behind his arrest and imprisonment, questions around his possible ties to US Intelligence and the mysterious circumstances surrounding his death remain subjects of speculation. Wallenberg’s story survives though, not only through the voices of those he saved but in official documentation, and it can be uncovered, along with the stories of countless other refugees and humanitarians, in Refugees, Relief and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II.

U.S. State Department Records Related to Calamities, Disasters, and Relief Activities, April 20 1946 File. April 20-23, 1946. TS Records of the Department of State Relating to the Problems of Relief and Refugees in Europe Arising from World War II and Its Aftermath, 1938-1949. National Archives (United States). Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BOHOPS859002355/RRRW?u=webdemo&sid=RRRW&xid=68765510

Interested in reading more about refugees or global politics using primary source archives? Check out: Escaping from Communist East Germany or A Global Security Crisis: A Future Under Threat.