│By Pauli Kettunen, Gale Ambassador at the University of Helsinki│

One of the best aspects of Gale Primary Sources is the ability to search all the text in the archives. This is made possible by Optical Character Recognition (OCR). With this technology, any text visible in the scans (effectively photos of the primary sources) is transformed into script which can be read by a search engine, allowing the user to find relevant content much more easily. Until recently OCR has only been an option with printed texts, which has left handwritten records far less accessible in text-based searches. This can be a serious hindrance in trying to find relevant sources, as I will showcase. In addition, deciphering handwriting which dates back over a hundred years is often a significant hurdle for anyone without much experience in palaeography; even if you find the documents relevant to your project, comprehending them is another matter.

In other words, the experience of many students deciphering historical handwritten documents today feels like playing a video game in “hard mode”, something that you cannot do unless you are prepared for a lot of frustration! Fortunately, as OCR technology has developed, Gale now provides an “easy mode” for handwritten primary sources! Like a supportive character in a video game, the Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) will help you on your quest to discover the secrets of fascinating old documents.

HTR in Gale’s archive ‘China and the Modern World‘

HTR was first introduced into a pre-existing Gale archive, Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture, 1790–1920. This was explored in a post on The Gale Review by my fellow student Ambassador, James Garbett. Now Gale has made HTR technology available in another archive: Hong Kong, Britain and China, 1841–1951, a module in the series China and the Modern World, and this is the archive I will examine in this blog post. Notably Hong Kong, Britain and China, 1841–1951 is the first Gale archive in which HTR was incorporated from the outset.

Searching metadata v. searching the full text

It is worth clarifying that without HTR, the search engine would only be searching the metadata of the handwritten documents; this includes information such as the source archive and collection, document number, title, and date. The implementation of the HTR technology in this archive means that the full text of each handwritten document is searchable, and consequently users will be able to get many more results in their searches. To simulate working with just the metadata, I searched for “trade” in the “document title” field (this can be done via the advanced search function). The result was a meagre 43 documents. Then I searched for “trade” again, this time choosing to search “entire document”. I received 1160 results this time. In this case, under four per cent of the documents with mentions of trade in the full text also included the term in the “document title” field of the metadata. Clearly searching the full text pulls back many more results which may be relevant to your research!

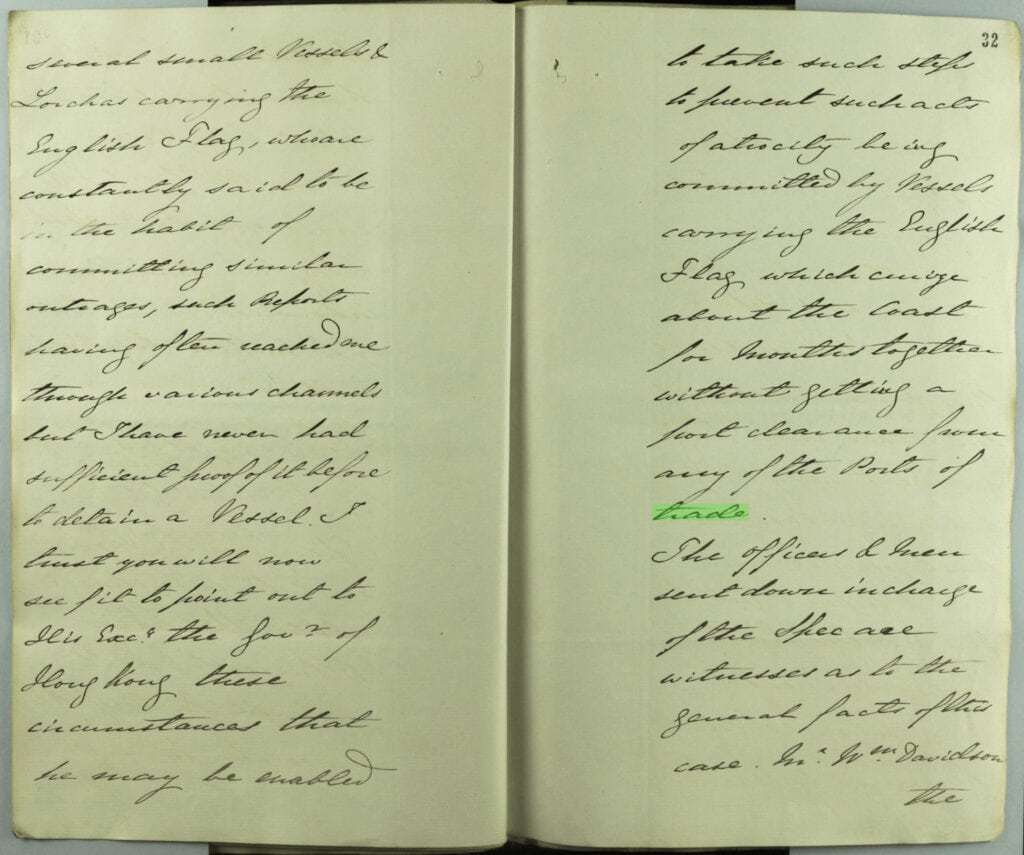

Offices and Individuals: 1848. 1848. MS War and Colonial Department and Colonial Office: Hong Kong, Original Correspondence CO 129/27. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/VYBXZS488610299/CFER?u=cferdemo&sid=CFER&xid=78c62ad6

I also love being able to see the front cover of this document!

Deciphering unfamiliar penmanship

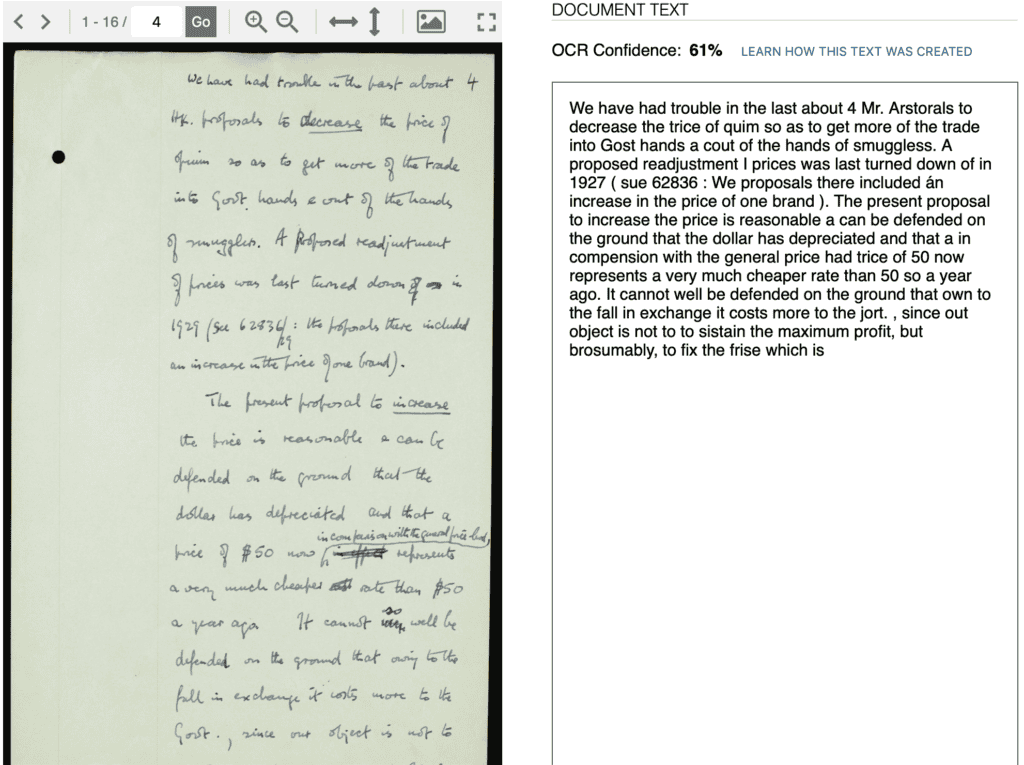

Nineteenth-century handwriting styles are reasonably uniform, producing especially good results with HTR, making Hong Kong, Britain and China, 1841–1951 a good collection for the technology. However, the documents will still be intimidating to people who are not yet familiar with this style of penmanship. To make browsing the sources even easier, the new upgraded interface of Gale Primary Sources allows users to view the original document image right alongside the HTR/OCR script for the relevant page, as shown in the screenshot below. This makes it faster to skim through documents written in hard-to-read handwriting, while being able to check the original text as needed. Downloading the full OCR script is also possible, should you have a use for it in your research.

Memorandum on Use of Opium: 1929 Nov. Nov. 1929. TS War and Colonial Department and Colonial Office: Hong Kong, Original Correspondence CO 129/520/8. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EGULTT120972154/CFER?u=cferdemo&sid=CFER&xid=744e813e

Use of handwritten documents in Digital Humanities

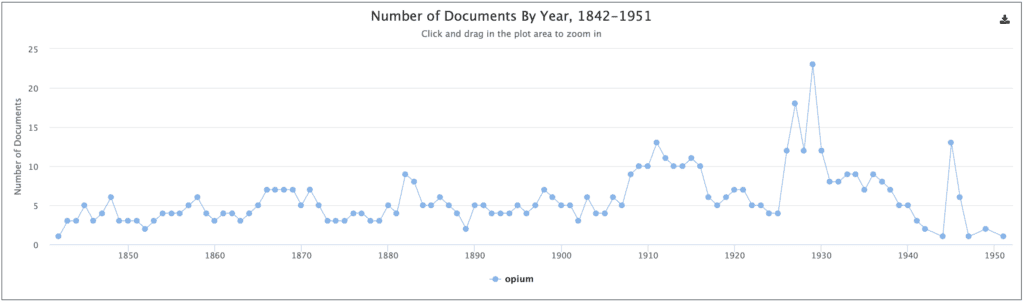

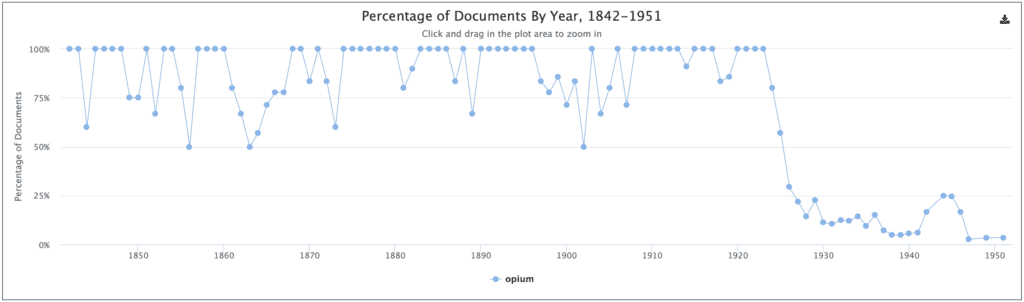

One of the upsides of the new HTR technology is being able to use the full text of handwritten documents in the Discovery Tools available in Gale Primary Sources – these are basic examples of Digital Humanities tools. Hong Kong became a British Colony after the first Opium War, and I decided to investigate how large a presence the drug had in official documents. I used the Term Frequency tool to produce the visualisations seen below. At first I was surprised to see how few documents each year mention opium. However, using the Term Popularity tool I could see that at least half of the documents each year until the early 1920s had at least one mention of the drug, thus the small number of hits was a result of the small number of documents in those years in this particular module. To elaborate on the difference between these tools, the Term Frequency graph shows the total number of documents which mention a search term each year; the Term Popularity graph shows the percentage of documents each year that contain the term.

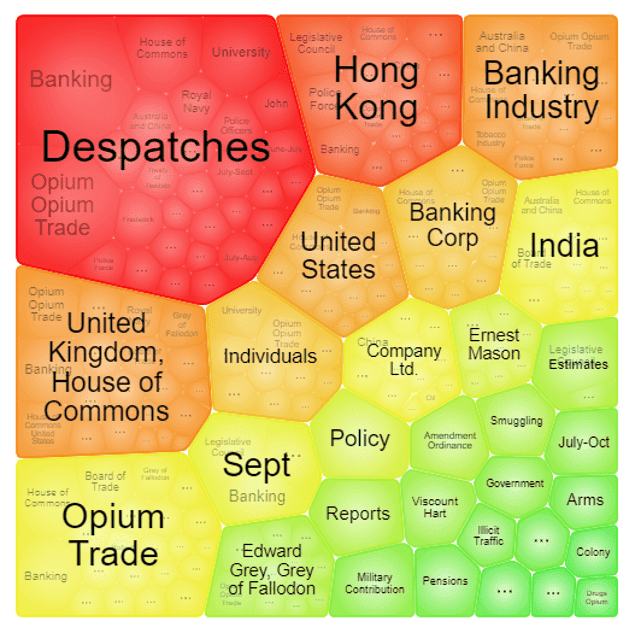

With the Topic Finder tool, it is possible to get more insight into the various contexts in which opium is mentioned in the archive. (This link will take you to view the tool right within the Gale Primary Sources platform, and the visualisation my results produce. It also allows you to toggle between tile and wheel view, as well as click the different sections and see the results within each tile!) The biggest section in the visualisation (also pasted in below) is “Despatches”, a word often used in the titles of document from the colonial office. “Hong Kong” and “United Kingdom, House of Commons” are the geographical and bureaucratic context for the writers, and thus written on many documents. For studying the effects of opium on Hong Kong, the documents under “Policy”, “Smuggling”, and “Illicit Traffic” might provide good information on the historical reality.

The tools above, available in Gale Primary Sources, are a simple form of Digital Humanities visualisation. The full text of handwritten documents in archives with HTR functionality can also now be incorporated into DH analysis conducted in the Gale Digital Scholar Lab. Whilst handwritten documents have previously been included in Digital Humanities projects, this has sometimes involved manual transcription which is extremely time consuming and thus the number of documents analysed is likely to be small. HTR technology brings handwritten archive sources on a par with printed ones, allowing far easier (and larger scale) incorporation in Digital Humanities projects.

All in all, HTR technology is a leap forward in the research of handwritten documents. Being able to search the full text of documents as well as include handwritten texts in Digital Humanities analysis will open the way for a more thorough understanding of the past.

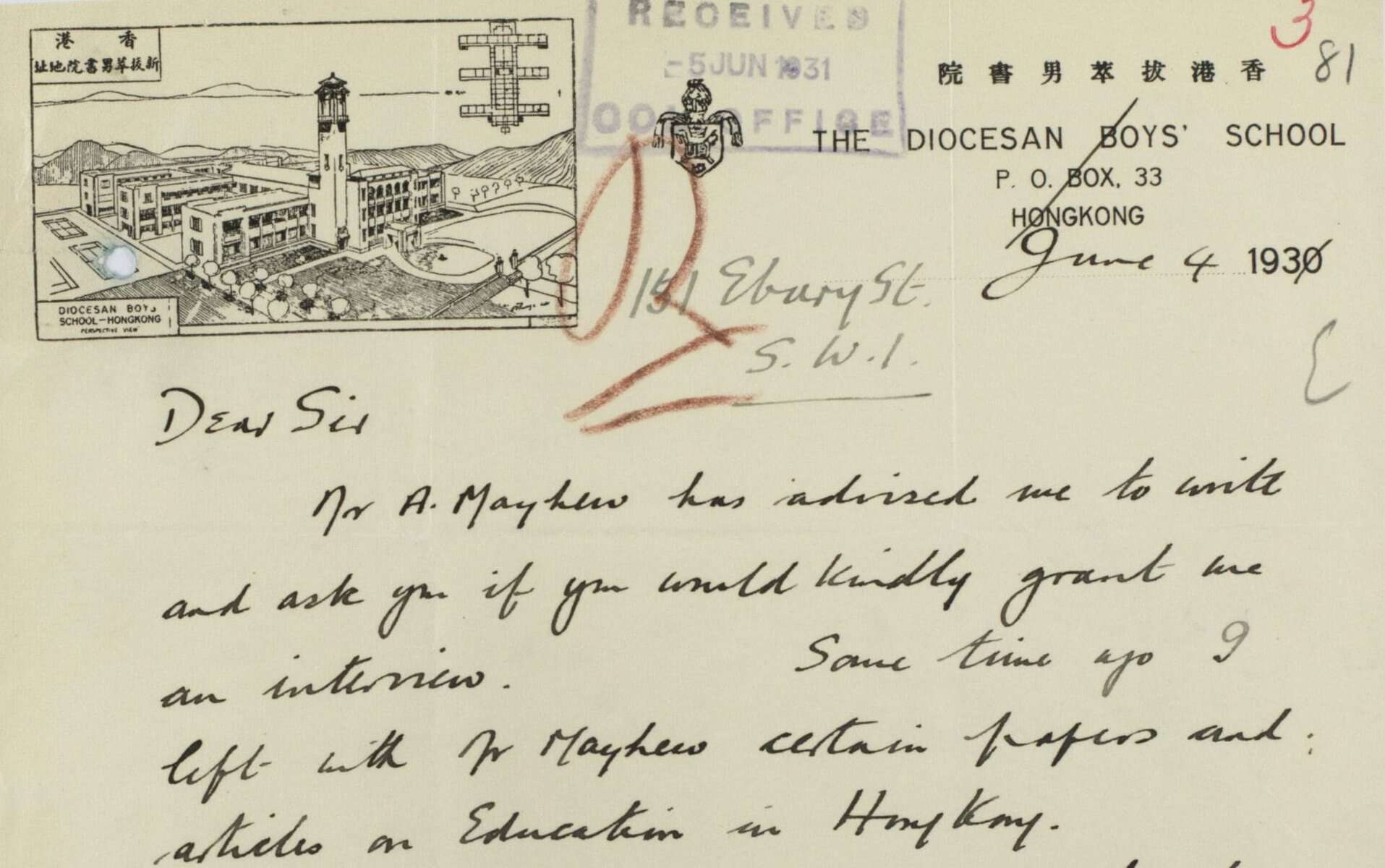

Blog Post Cover Image Citation: Diocesan Boys’ School and Orphanage: Appeal for Money: 1931 Jan. 2-1932 May 10. January 2, 1931-May 10, 1932. TS War and Colonial Department and Colonial Office: Hong Kong, Original Correspondence CO 129/529/1. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EVQSQI624197851/CFER?u=webdemo&sid=CFER&xid=4c59c065 p.78

Nb. This archive is not available at the University of Helsinki; Gale granted me access as a Gale Student Ambassador so I could explore the Handwritten Text Recognition technology.