by Seth Cayley

Can cocaine really cure sea-sickness? Something tells me that very little peer-reviewed research has been done on the subject in recent years. But that didn’t stop the Victorians. From around 1870-1915 a large number of narcotics, including heroin, were widely and legally available, and often packaged as medicines. Historians have dubbed this period before the first international drug control treaties as “The Great Binge”.

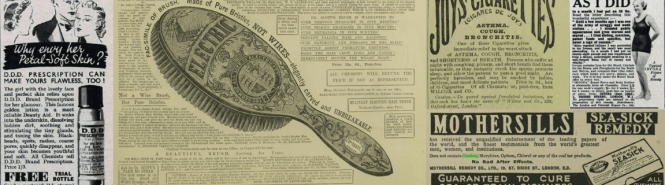

I first came across The Great Binge when browsing through bound volumes of the Illustrated London News for the first time at university. While I was supposed to be looking for news items about pre-First World War Europe, my eyes kept on being drawn to the adverts. Leafing through these, I learnt that: smoking Joy’s cigarettes could help with bronchitis; a certain brand of men’s underwear does not shrink; and that an electric hairbrush could cure my “nervous headache” (although I was pretty certain my headache that day had other causes common to students).

One item in particular caught my eye. It was a recurring advert in the 1910s for sea sickness pills that proudly claimed that they did NOT contain cocaine. Intrigued, I soon realised I was witnessing the end of a period where today’s illegal drugs were treated as everyday medicine. Subsequent reading would reveal Victorian opinion pieces that were essentially product reviews of drugs. Cocaine certainly worked for the journalist Florence Fenwick-Miller in 1891 in fending off “the horrid feeling of prostration and exhaustion” of sea travel…although she did think that it was ultimately inferior to champagne and brandy for longer voyages.

This is the real joy of studying historical newspapers. Even the throwaway material such as advertising can reveal hidden gems about how people lived in the past, how they spent their money, their attitudes towards personal health, and even what pants they wore.

I invite you to learn more about digital newspaper collections by viewing a recent webinar addressing this topic.