Undoubtedly, many still appreciate and celebrate the deeply religious roots of Christmas, yet it has also become a commercialised event in many countries today. From mid-November, high-streets are packed with snowflake window stickers, festive deals and cheery Christmas music to entice shoppers into an economically indulgent mood. Yet, despite the general consensus and participation in commercialising Christmas, this is often assumed to be a new phenomenon, part of today’s world. ‘Born to Buy’, an article in Gale’s Academic OneFile, offers an example of such sentiments;

“While this celebration still brings up a homely picture of tranquillity, the truth is that Christmas is characterized more by frenzied shopping…and overspending…Two generations back, my Norwegian grandmother was overjoyed as a child when receiving one modest gift…”[1]

However, delving into Gale’s newspaper platform, NewsVault, quickly reveals that the increasing commercialisation of Christmas has been underway for longer than many realise. Using Gale Artemis: Primary Sources, I cross-searched several key newspaper archives, and applied handy filters to narrow my results to ‘advertisements’.

It seems Christmas commercial adverts began to appear in quantity in British newspapers from the mid-nineteenth century. This may have been the result of several factors; industrial development enabling mass production, lowering product costs and increasing wealth, giving more people a disposable income. Both allowed increased gift purchase, which enterprising businesses were quick to recognise. Thus nineteenth-century advertisements reflected social situations already commercialising Christmas, and stimulated consumerism by encouraging purchases.

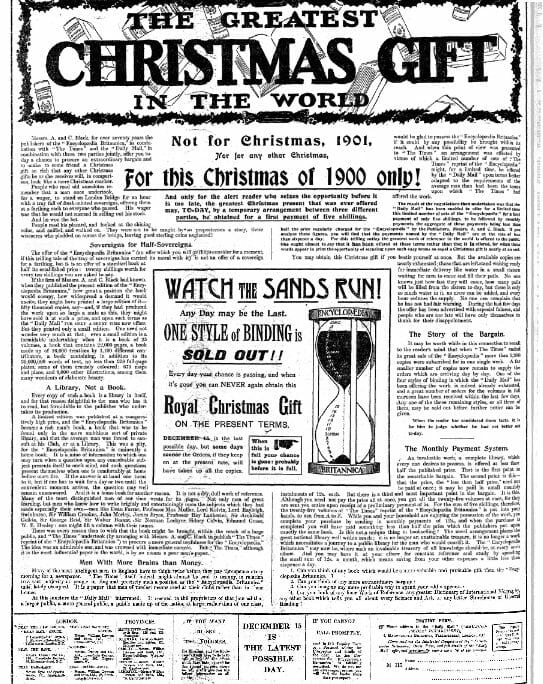

Interestingly, one can find similarities in sales technique with modern adverts. While we may feel ‘urgency’ is a sales technique characteristic of our modern consumer culture, ‘hurry while stocks last,’ and ‘this year only’ are far from twenty-first century phrases.

Through language and imagery this advert evokes panic, suggesting the urgent, fashion-buying mentality that’s stimulated and seen in today’s Christmas shoppers was already used and effective in Victorian Britain. This contrasts with adverts shortly prior and simultaneous to the above which chose to emphasise the utility of the items they advertised, perhaps suggesting Christmas was still about useful, required gifts rather than an exercise in unnecessary over-indulgence.

A more shrewd interpretation is that such adverts reflect a social awareness that Christmas was already becoming a festival of unnecessary gifts; such adverts were seeking to distinguish themselves from increasing competition by emphasising utility.

An article from the Illustrated London News in 1895 also supports the view that Christmas was already fleeing its religious roots and the innocent and traditional ‘Christmas card world’ that many believe characterised a Victorian Christmas, suggesting the cartoons and images found on modern merchandise – and which arguably contribute to a sense of unsavoury commercialisation – were already a part of Victorian festivities.

Advertisements in the first half of the twentieth century reflect several social realities relevant to the commercialisation of Christmas. Changing relations between the sexes are evident in the targeting of promotional material. Whilst previously the main readership of publications such as the The Times was male, we increasingly find adverts targeted directly at women, suggesting not only that more women were reading these papers, but that women were more economically independent and increasingly active participants in commercial activities for leisure. The advert below from the The Times in 1927 is clearly marketed towards a female buyer.

The boom in marketing in the 1920s was also caused by the positive knock-on effects in many countries of the robust economy and affluence of 1920s America which increased disposable incomes and the commercialisation of Christmas. The extravagance of gifts such as that below indicate a time of relative wealth and abundance.

It is interesting to compare these adverts with those from the 1930s and ’40s, when the world was hit by the frugality of World War II. One trend in gift-giving in these years was the use of savings tokens, which were part of the wartime National Savings Committee’s efforts to discourage frivolous spending and encourage public investment in the British war effort, and are indicative of a world in which access to commodities was limited.

Commercialisation did not, however, stop during the war; alternative persuasive techniques were adopted. The focus in the advert below is the war, not Christmas; buying these toys no longer seems like a commercial transaction, but meeting vital needs; helping loved ones through hard times and by such means, fighting the Homefront. Yet ultimately it is still persuading readers to buy gifts for Christmas. Thus even in the austere years of WWII, the commercialisation of Christmas continued.

The relative prosperity that characterised the 1920s was seen again in the decades following World War Two and, along with global trade, led again to a surge in commercialisation, contributing to the development of global brands in the second half of the twentieth-century, which have had a significant role in commercialising Christmas.

Today, sentiments I have heard, such as that Christmas is heralded by the appearance of the Coca Cola advert on TV, indicate how extensively Christmas is now commercialised. Interestingly, it has even been argued that some ‘narrative Christmas adverts’ are actually escaping their consumerist foundations; becoming an art form – part of ‘Culture’. A National Review article in Global Issues in Context focuses on one such advert produced by the supermarket Sainsbury’s in 2014, which depicted the football match held during the Christmas Day Truce of 1914[3]. ‘The imagery’, it suggests ‘is striking, the actors’ performances powerful, and the narrative haunting…An advertisement that uplifts the soul is not merely an ad; it is a work of art.’ Ultimately, however, the main purpose of advertisements is still brand promotion. Catching viewers’ attention with narrative material is a means of stimulating discussion and subsequently increasing sales. Still, the modern trend of tying commercial exercises to a powerful and pervasive ‘higher’ culture is another reason the commercialisation of Christmas is so extensive. Yet an exploration of the Gale archives has shown this is also because the process has been underway and increasingly ingrained in the experience of Christmas for far longer than many realise.

[1] Anja Lyngbaek, “Born to buy?” AMASS 18.3 (2014): 22+. ACADEMIC ONEFILE

[2] ‘This year’s Christmas advertisement from the British grocer Sainsbury’s has brought out the Grinches’, National Review 8 Dec. 2014: 11, GLOBAL ISSUES IN CONTEXT