By Rebecca Bowden, Associate Acquisitions Editor

On 29 March 1984, at 10:25pm, Channel 4 aired ‘The Other Face of Terror’. According to Elizabeth Cowley, writing for the Daily Mail, ‘if I didn’t know this documentary was fact and that the people we see and hear…were real, I’d swear it was an over-the-top political thriller.’ The hour and a half film, by Dutch director Ludi Boeken, exposed a ‘vast neo-Nazi network of terrorists, arms dealers and theorists’; it also exposed one of the key figures in the British National Party (BNP) and the British Movement as a mole for anti-fascist investigative organisation Searchlight. That man was Ray Hill. Using Gale Primary Sources, we explore his experience with the far-right.

Ray Hill was born in Mossley in 1939. He joined the army at seventeen, following in the footsteps of his father. Writing for The Times, he describes how he left the army in the early sixties and was living in Leicester when he came across an anti-immigration advert. It was the first time he had been interested in politics, but he quickly became involved in the anti-immigration movement. In an interview, available in Gale’s Political Extremism & Radicalism archive, Hill describes this first encounter with the British far-right:

‘I picked up some literature from an outfit calling themselves the “Racial Preservation Society.” And it was right at the sort of beginning of the influx of immigrants here. Particularly into Leicester. Leicester was sort of a favourite settling place for many of them. And this Racial Preservation Society was active, as was an outfit calling themselves the “NDP” the National Democratic Party…And I took an interest in it.’

Attracted by the strong anti-immigration stance of the Racial Preservation Society, Hill found himself drawn into the world of the far-right.

How then, does a far-right supporter become a mole, reporting on the people he had once seen eye-to-eye with? In 1969, Hill moved to South Africa, which was in the midst of apartheid at the time, and it was this that radically changed his mind. As he puts it:

‘nobody with much humanity about them can stay in South Africa for ten years and not come to dislike apartheid. It’s just so horrible, you know. Just horrible. I mean people being arrested for falling in love, you know. That sort of thing. Bloody awful.’

This, combined with the fact he had made Jewish friends, meant he left his earlier views behind him. It was not a ‘Damascene Conversion,’ he emphasises in The Times, but ‘a gradual change in [his] attitudes caused by the people [he] was mixing with.’

So, when the National Front of South Africa came into existence, Hill found himself re-joining; this time, however, it was at the request of a Jewish friend, who asked him to report back on what he saw and heard. Ray Hill had become a mole.

Hill attended around two-dozen meetings, even becoming chairman, before he returned to the UK and was put in touch with Gerry Gable, founder of Searchlight. It was Gerry’s idea for him to infiltrate the far-right in the UK on behalf of Searchlight, and ‘in no time at all [Hill] was Deputy Leader of the BNP.’

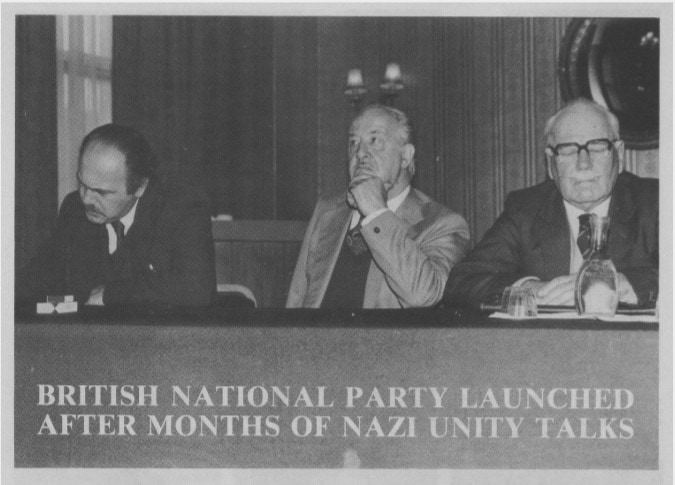

“British National Party Launched after Months of Nazi Unity Talks.” Searchlight Magazine, May 1982, p. 3+. Political Extremism & Radicalism, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/747zr9. Accessed 19 Sept. 2018.

Hill publicly exposed himself as an infiltrator when he left the BNP five years later and has continued to talk about his experiences since. It is these discussions, including the audio interview featured in Gale’s Political Extremism & Radicalism archive, that provide the researcher with a different angle on the far-right at the time.

Firstly, let us look at Nicky Crane. Nicola Vicenzio Crane was active in the British Movement, was jailed multiple times for racist attacks and was one of the founders of neo-nazi group Blood and Honour (see sources in both Political Extremism and Archives of Sexuality & Gender). Somewhat oxymoronically, in 1992, Crane came out as homosexual, a year before he died of AIDS (see source 1; source 2). It is difficult to find a positive description of him in Gale Primary Sources. Searchlight Magazine describes him as ‘one of the foulest and most violent nazi thugs’, and a ‘psychotic lump of trash’. An audio interview with anti-fascist activist Anna Sullivan in Political Extremism states:

“You couldn’t miss him, either. Physically, he certainly stood out…he’d been imprisoned at least once or twice for a GBH attack, because, you know, he was really vicious. And I never really met him face to face. I saw him when we did the march past his house…we got so many of the local Asian community involved, and, you know, that’s the key, really. And all these wonderful women, you know, in their saris and headscarves were carrying placards saying, “We will not be bullied by these racists.”

That same rally, in which nearly 300 anti-fascists, led by then local-MP Jeremy Corbyn, marched to the home of Nicky Crane and other known Nazis, was also covered by Searchlight magazine.

Hill’s interview in the Searchlight Oral Histories Collection is the only instance to paint a different picture:

“I liked Nicky. I always thought he was a likeable, kind-hearted, but misguided young man. Obviously, with a massive chip on his shoulder, but good at heart.”

Here we see a more personable side to Nicky Crane, something that would be lacking were it not for these first-hand testimonies featured in Political Extremism & Radicalism. It is an insight into how Hill could have stomached being a part of the far-right for those five years he was a mole. As he puts it:

‘Some of the kids that were pulled in were genuine people who wanted a better world for themselves and their offspring…Well, you can’t condemn them for that.’

This reminds us that there are multiple facets to every personality, even those whose ideologies many would class as unpleasant. It also enables researchers to look beyond the movement as whole, and instead begin to understand the individuals involved.

Hill’s testimony also reveals what happens after the mole has been outed: the repercussions. This part of his story is corroborated by news reporting of the time. The Sunday Telegraph, for instance, offers an article titled ‘Nazi threat of death for author’, detailing how ‘the most dangerous nazi group in Europe…plans to kill him in revenge’ and that he even has a panic button to the police station in his house. In The Times, we hear of vandalised cars and threatened children. One Searchlight Magazine story reported that ‘police in rural areas of England…have launched a round-the-clock watch on his house’ after a hit team turned up at his door, while another tells how his home was ‘attacked by a nazi firebomb squad over the May bank holiday’ of 1988, with the words ‘Kill Hill’ daubed on his front door. Similarly, in his interview, Hill discusses having his caravan set on fire while his children slept inside and having bricks repeatedly thrown through windows. He jokes that he ‘must have been the only man in England to pay a f****** glazier by banker’s order’. Jokes aside, his disgust and anger are obvious, describing it as ‘utter, utter evil.’ Again, we get the opportunity to understand the personal side of the story, alongside the more formal reporting.

The political life of Ray Hill then, is full of drama and intrigue. He has since devoted the rest of his life to anti-fascist work, giving talks that highlight the dangers of the far-right. He suggests he will continue to do so whether he is 75, or 95. The press tells of a far-right BNP leader who revealed himself to be a mole, and of the difficult aftermath that followed. It is only through Hill’s own testimony that we get a true sense of the man, his journey and the personal side of the story; of the people he was interacting with and the emotional struggles he had to overcome.

Across the Gale Primary Sources platform researchers can view a variety of content from political ephemera and oral history interviews in Political Extremism & Radicalism to newspaper articles in The Telegraph, The Times and The Daily Mail thus providing scholars with a broad and in-depth view of this episode of history, from multiple angles.