│By Rachel Holt, Senior Acquisitions Editor, Gale Primary Sources│

When we think of feminism, names like Harriet Martineau or Mary Wollstonecraft often come to mind—not Queen Victoria. After all, in an 1870 letter to Sir Theodore Martin she called women’s rights activists “mad, wicked folly.”

Her reign from 1837 to 1901 however tells a more nuanced story and although Queen Victoria may not have embraced the women’s suffrage movement, her life and leadership challenged the rigid gender norms of her time, making her an inadvertent feminist icon.

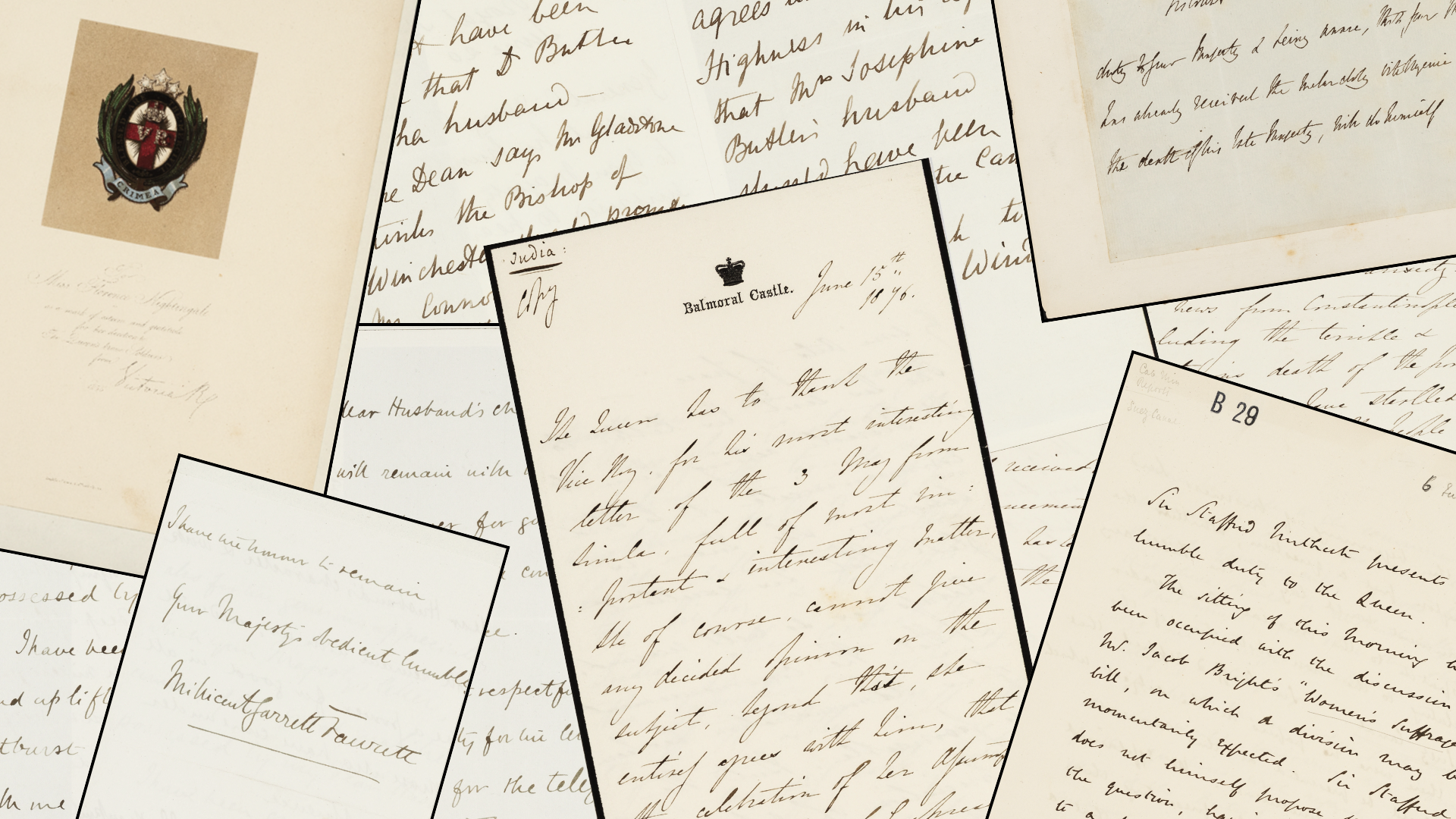

The latest expansion of the extensive State Papers Online programme sees the launch of State Papers Online: Nineteenth Century with its first instalment as the State Papers of Queen Victoria and King Edward VII. Hosting two unique collections from the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle, this resource contains correspondence between the monarchs and their governments, representing Queen Victoria and King Edward VII’s state papers. It enables researchers to explore questions such as these.

Ruling In a Patriarchal World

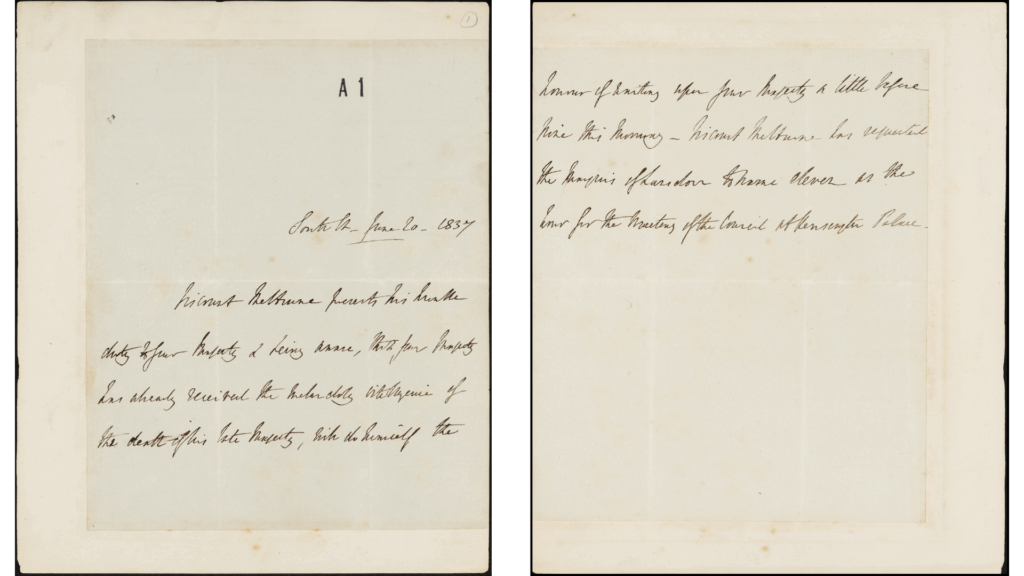

In 1837, Victoria ascended the throne at just eighteen years old, inheriting a kingdom where women were expected to remain in the domestic sphere. Her rise was revolutionary: she became the head of state in a world dominated by men, ruling over the largest empire in history. Lord Melbourne, her first Prime Minister, became her mentor, guiding her through early political challenges.

The State Papers of Queen Victoria and King Edward VII, as well as hosting correspondence between the monarchs and their ministers on a variety of domestic and foreign issues, also contain daily memos from the Prime Minister. These memos provide evidence of how Queen Victoria learned from, advised, and negotiated with her premiers as well as documenting this formative relationship with Lord Melbourne. Their partnership demonstrated that a young woman could command respect and authority in the highest circles of power.

Redefining Female Power

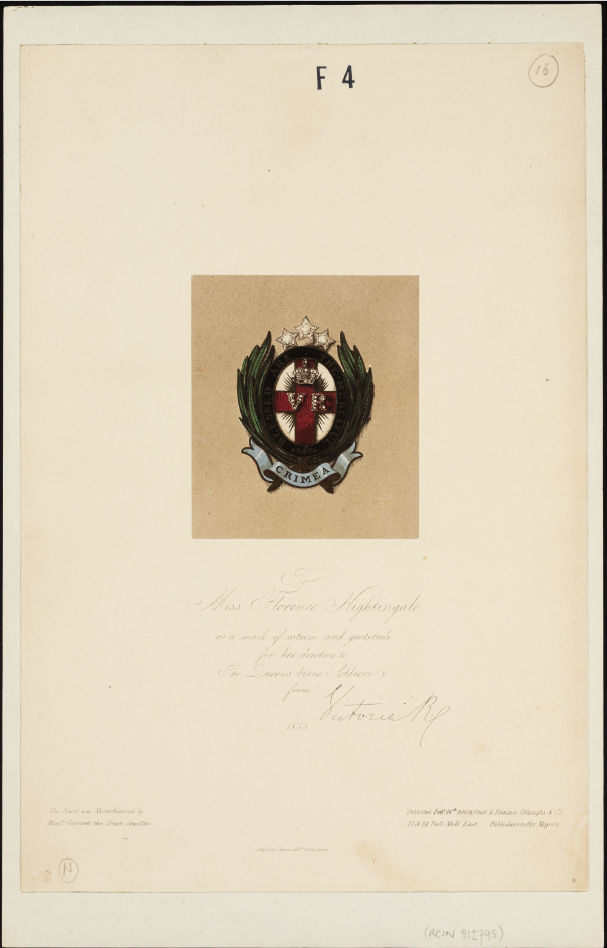

Queen Victoria’s reign was not merely symbolic. She actively engaged in state affairs, corresponded with prime ministers, and influenced foreign policy. During the Crimean War (1853–1856) for example, Victoria took a keen interest in military strategy and welfare. She personally awarded Florence Nightingale for her work, reinforcing the idea that women could lead and innovate in times of crisis.

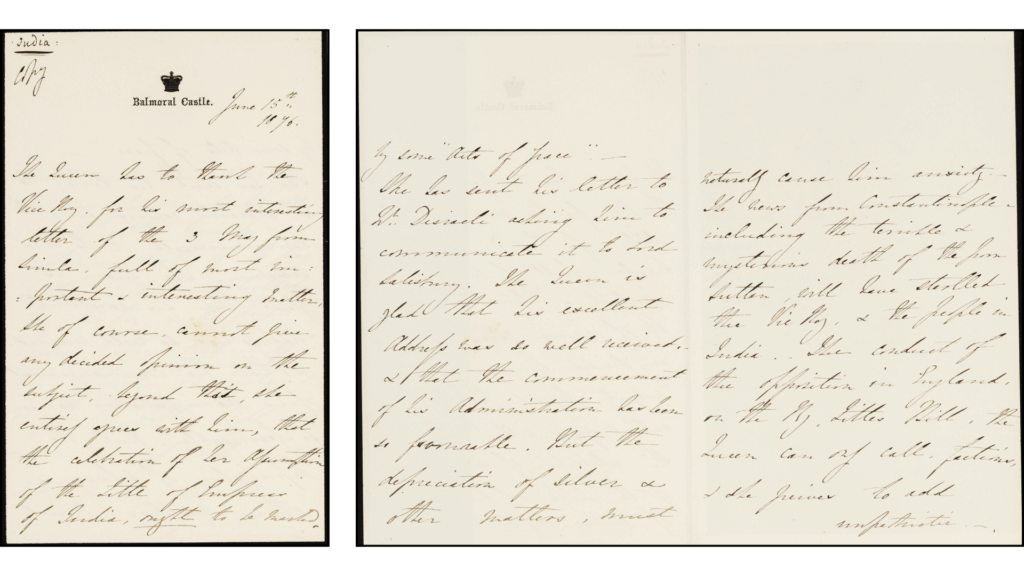

Furthermore, Victoria was not only the ruler of a nation but reigned over the British Empire and she in turn became a global symbol of female authority. This was officially recognised in 1876 when Benjamin Disraeli named her Empress of India. Correspondence between Her Majesty and Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, the Governor-General of India reveals how the assumption of the title was received in the colonies.

The Paradox

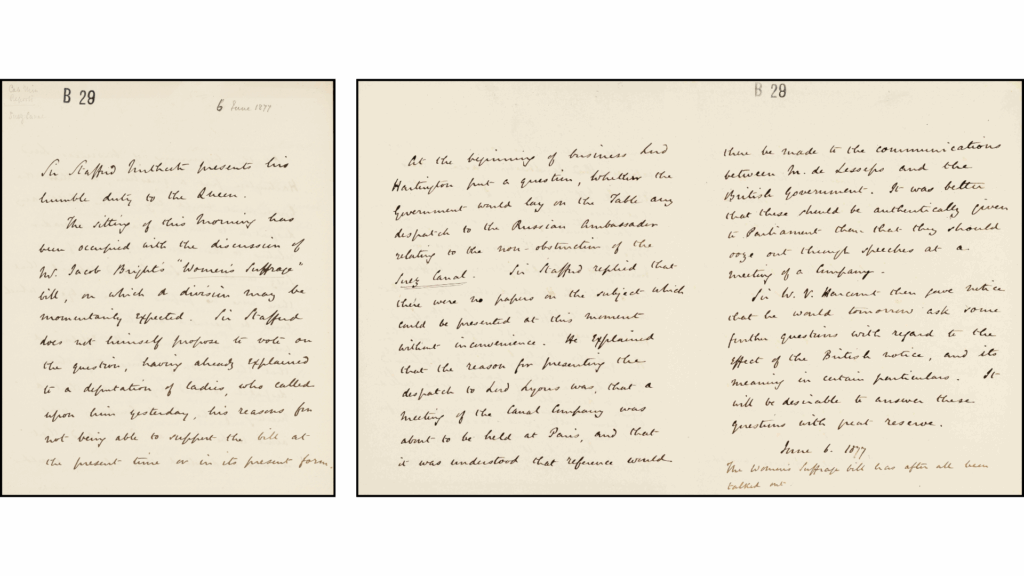

It is often therefore a surprise to the modern world that Queen Victoria opposed women’s suffrage. Despite her own position she feared it would disrupt the social order. Although she never spoke out publicly against the Women’s Suffrage Bill, she closely monitored its discussion in government as demonstrated in various communications between her and her ministers.

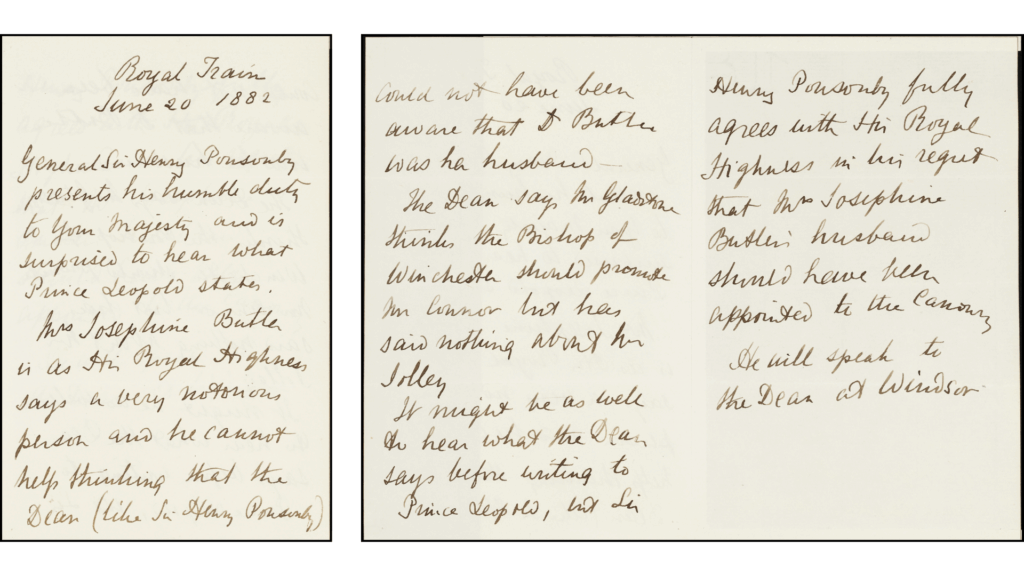

As well as the various protests and petitions of Josephine Butler, who she is suggested to have described as a “very notorious person”.

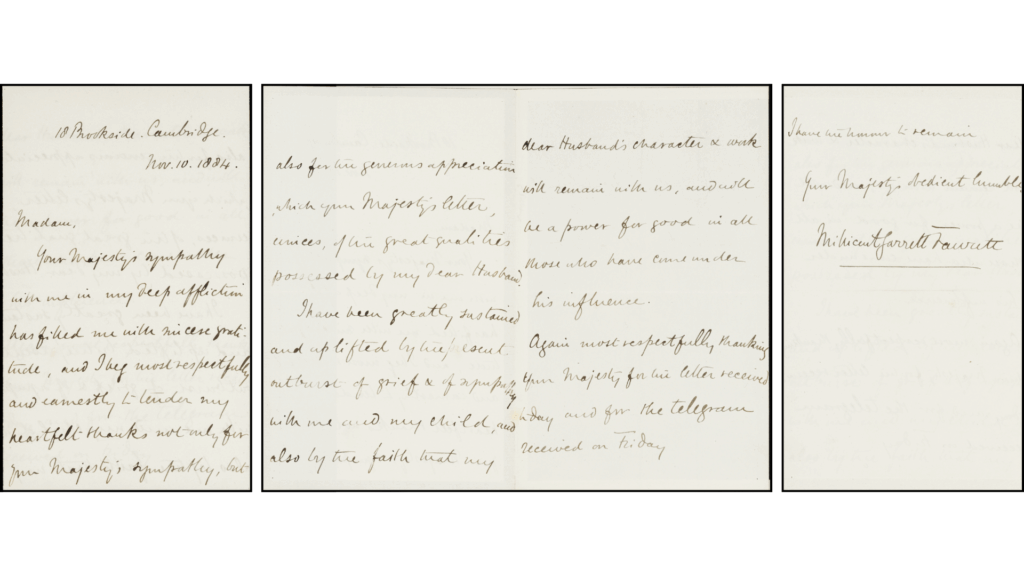

The monarch also had communication with political activist and writer Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett who led Britain’s largest women’s rights association, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies.

Indeed, her son, King Edward VII would go on to monitor the Women’s Social and Political Union and the activities of Emmeline Pankhurst and (later) Christabel Pankhurst.

An Accidental Feminist Icon

Queen Victoria’s story is a paradox. She resisted women’s suffrage yet embodied their core principle: that women are capable of leadership and influence. In doing so, she became an accidental feminist icon, inspiring generations to rethink what women can achieve.

Victoria’s life demonstrated that women could wield immense power and influence. Even if she didn’t advocate for systemic change, her reign inspired conversations about gender roles and leadership. Don’t forget that Victoria had to navigate a complicated world where she had to balance her divine right to rule as sovereign with being a woman in a patriarchal society.

Today, Queen Victoria’s legacy resonates in academic discussions about queenship and women in power. Fascinating topics that can be explored further through the newly digitised materials in the State Papers of Queen Victoria and King Edward VII. She was not a feminist by ideology but paved the way for future female leaders.

If you enjoyed reading about Queen Victoria and her state papers, check out these posts:

- Using Literary Sources to Research Late Nineteenth-Century British Feminism

- ‘A Tale of Two Collections’: The Stuart Papers and Cumberland Papers at the Royal Archives, Windsor Castle

- How Might a Cultural Scholar Use State Papers Online: The Stuart and Cumberland Papers?

Blog post cover image citation: A collage of images from the archive.