|By Liping Yang, Senior Manager, Academic Publishing, and Lindsay Whitaker-Guest, Associate Editor, Gale Primary Sources|

Gale has just released China and the Modern World: Regional China and the West, 1759-1972. As the ninth instalment in the series, this new archive features a compilation of 39 series of mostly British Foreign Office (FO) files. These include general correspondence and registers composed by the British legation in Beijing as well as British consulates based in more than 20 Chinese coastal and inland treaty ports.

Also included are the private and semi-official correspondence of Sir Henry Pottinger, Sir John N. Jordan, and Lord Edmund Hammond as well as the records and photographs of the British concession in Tianjin. This post will explore a few of the topics and events which can be studied through this new archive.

Treaty Ports

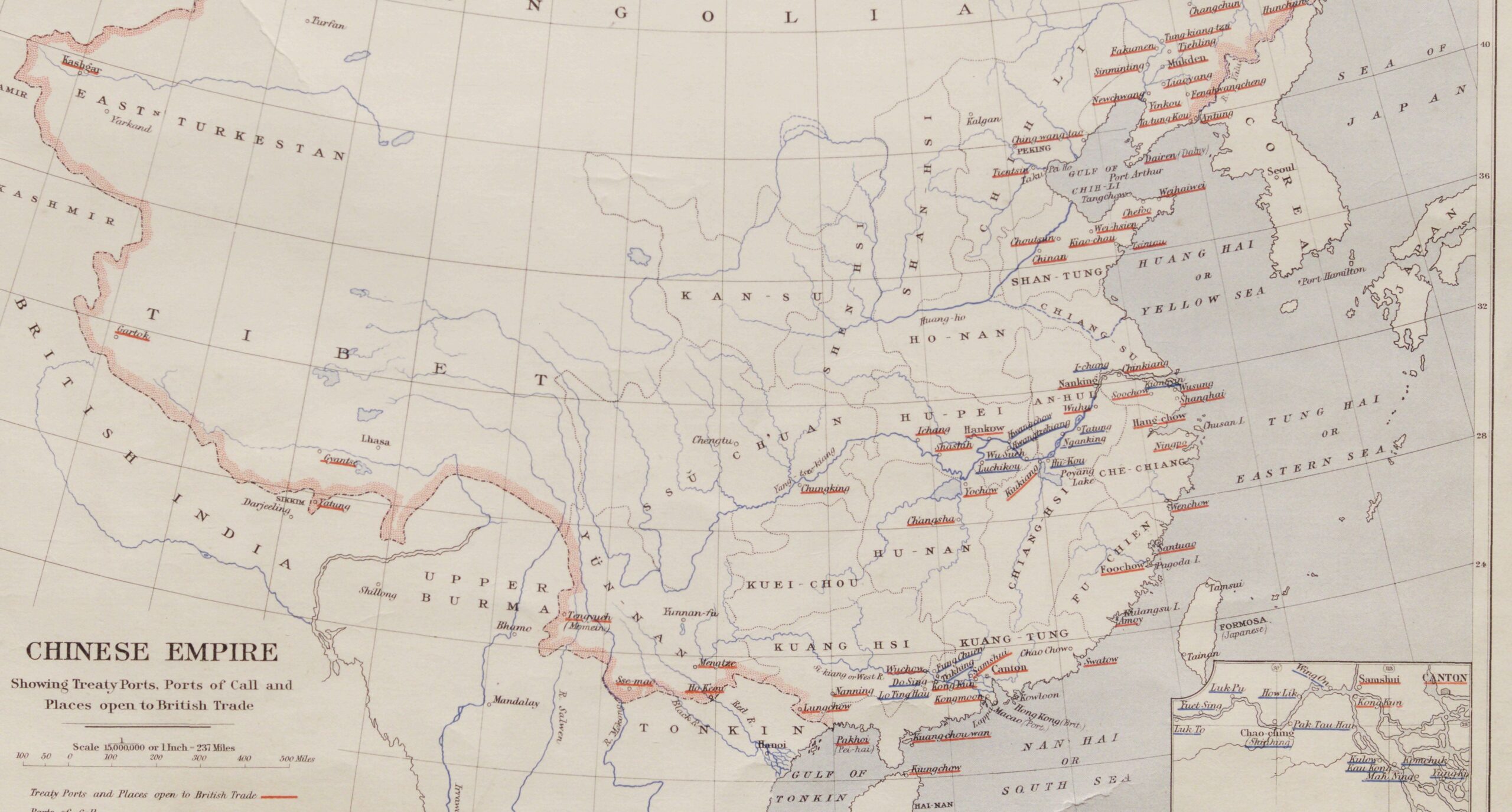

China’s Qing Dynasty was defeated by Great Britain in the first Opium War and forced to sign the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. The Treaty stipulated that China should open five coastal ports for trade with Britain and other Western countries. These include Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. Hence the origin of treaty ports.

From 1842 to the early twentieth century, more than 80 treaty ports were established across China, including both coastal and inland port cities. As a symbol of Western influence in China, these ports were regional centers across China where foreign trade, business, diplomatic and consular, and political activities were conducted. They were also where foreign consulates, concessions/settlements, companies, and legal courts were based. The British legation in Peking and these consulates across China generated a huge amount of valuable material, which forms the core of this new archive.

Records of Land Transactions

Land transactions in the form of land leasing and transferring for commercial, governmental, residential, military, and other purposes were conducted extensively in Tianjin, Shanghai, and other treaty ports. Such transactions usually involved British government representatives such as consuls, the Chinese authorities, surveyors of the British Office of Works, and foreign firms and merchants.

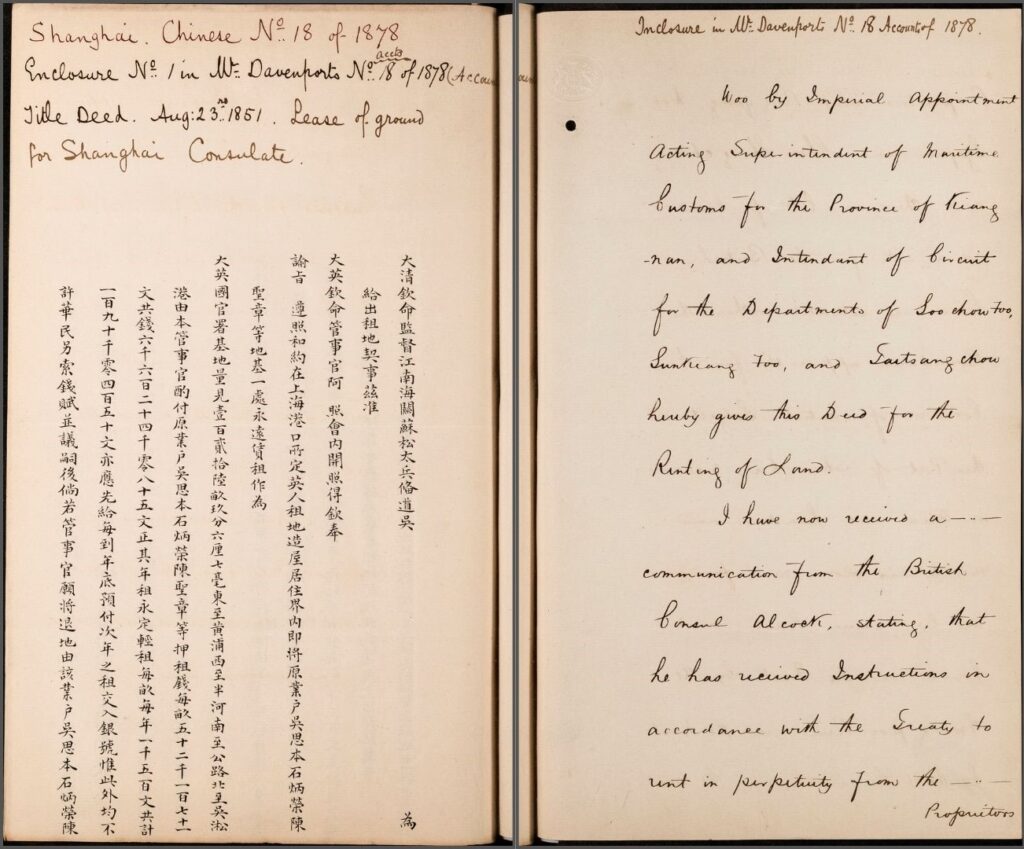

One good example of such transactions is a title deed signed between Rutherford Alcock, the British Consul in Shanghai and H.E. Wu Jianzhang, the Shanghai Taotai, in 1851 for the perpetual lease of a piece of land originally owned by three Chinese subjects for building the British Consulate. Below are the first pages of the title deed in Chinese and its English translation.

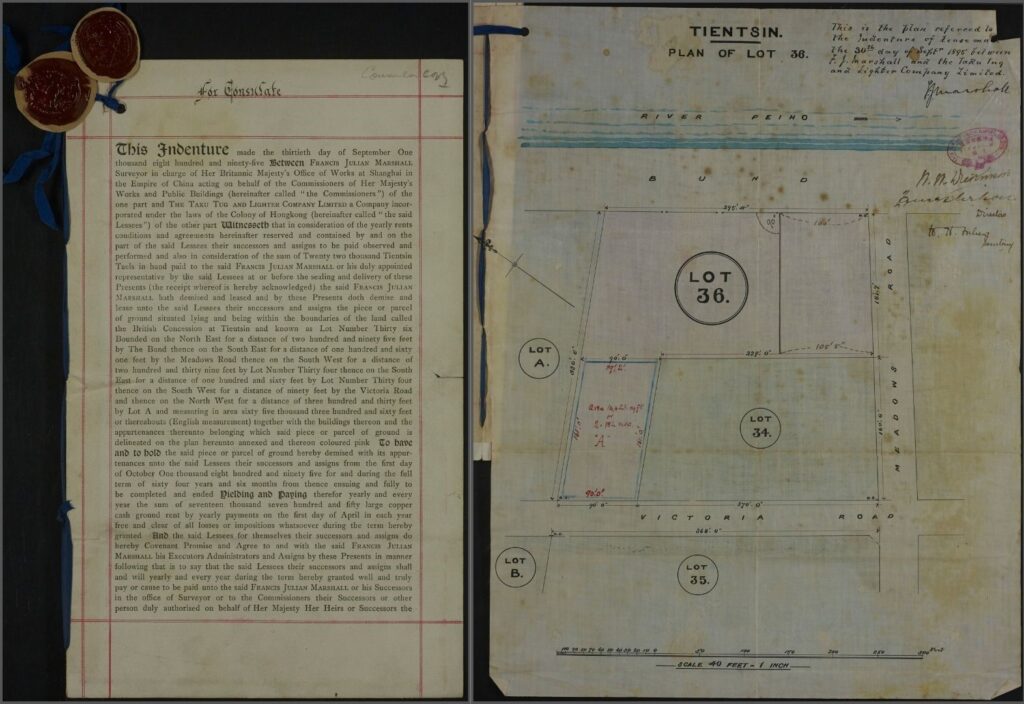

On September 30, 1895, an indenture was signed between Francis Julian Marshall, Surveyor in charge of Her Britannic Majesty’s Office of Works at Shanghai in the Empire of China and The Taku Tug and Lighter Company Limited, a company incorporated under the laws of the Colony of Hong Kong, on the lease of Lot 36 within the British concession in Tianjin for 64 years and 6 months. Attached to the contract is a plan showing the lot’s location.

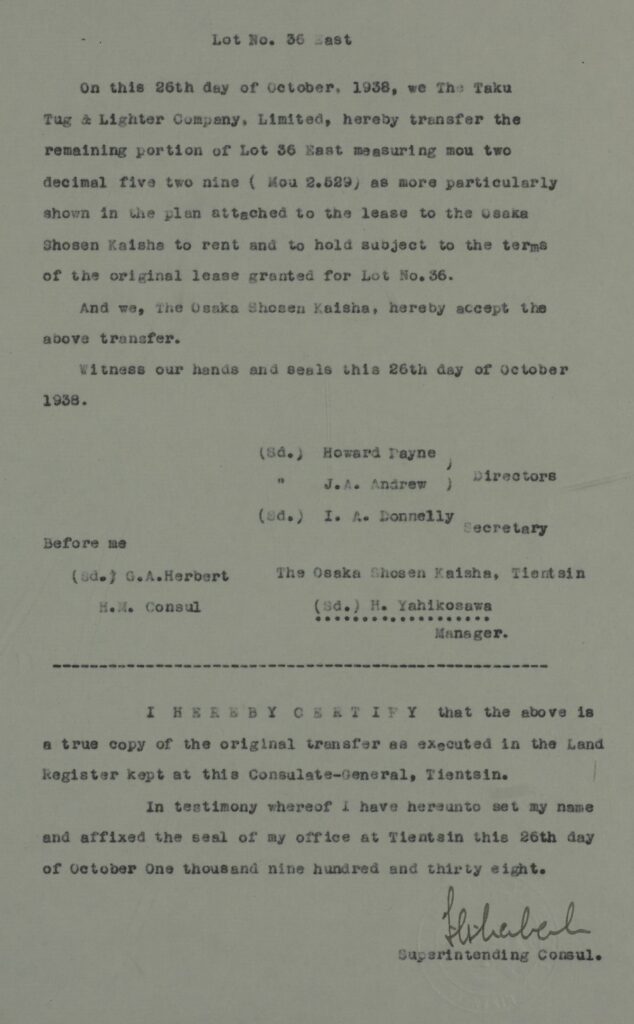

Interestingly, in the subsequent years, the lessee Taku Tug and Lighter Co. transferred part of Lot 36 to other firms, including a merchant called Alexander Hugh Mackay in 1905. In October 1936, another part of the land was transferred to the Japanese company Osaka Shosen Kaisha. The transaction records of this particular lot indirectly reflects the rise and fall of British and Japanese influence in China from the late nineteenth century until the 1930s, prior to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Local Conditions

The general correspondence included in the consulate records is useful for ascertaining the local social and political situation of Chinese treaty ports. The Tientsin Massacre of June 1870 saw around 60 French missionaries and Chinese converts killed by a Chinese mob. The mob was agitated by rumours that French missionaries kidnapped and killed Chinese children to remove their eyes for medicines.

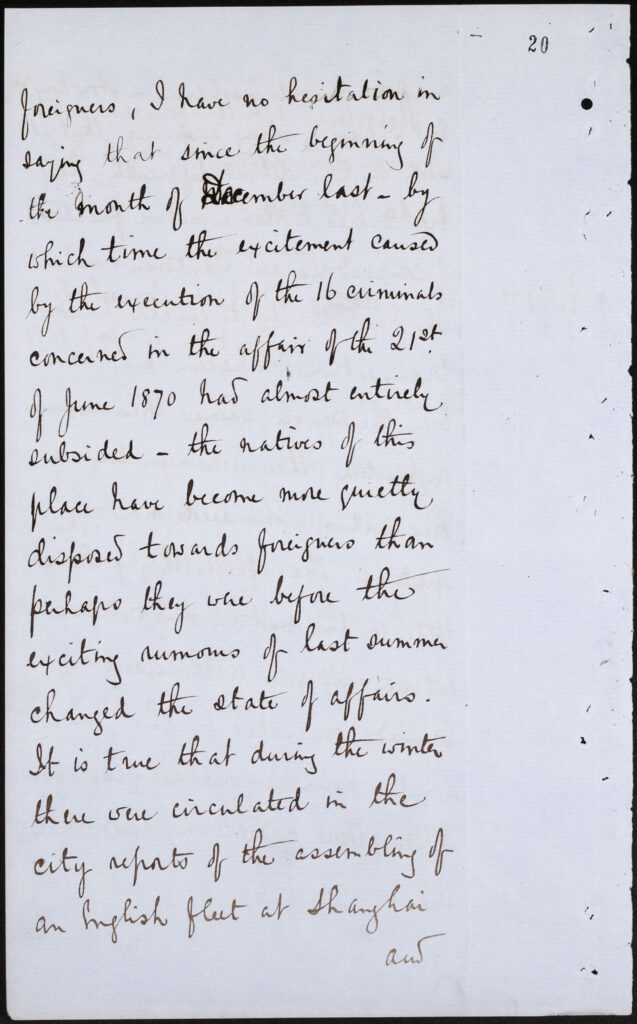

After the incident was put down with the “execution of the 16 criminals concerned in the affair,” relations between foreigners and Chinese natives in this northern Chinese treaty-port city took a positive turn. According to the British consul at Tianjin in a despatch dated April 10,1871 to the then British minister (Sir Thomas Wade), “the natives of this place have become more quietly disposed towards foreigners than perhaps they were before the exciting rumours of last summer changed the state of affairs.”

The outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941 led to Great Britain and the United States’ decision to relinquish their extraterritorial privileges in China in 1943 through two separate treaties with the Chinese nationalist government. This, along with the Chinese Civil War that started shortly after the end of WWII, had exacerbated the conditions for foreign firms in the treaty ports, which affected the wellbeing of Westerners residing in these treaty ports.

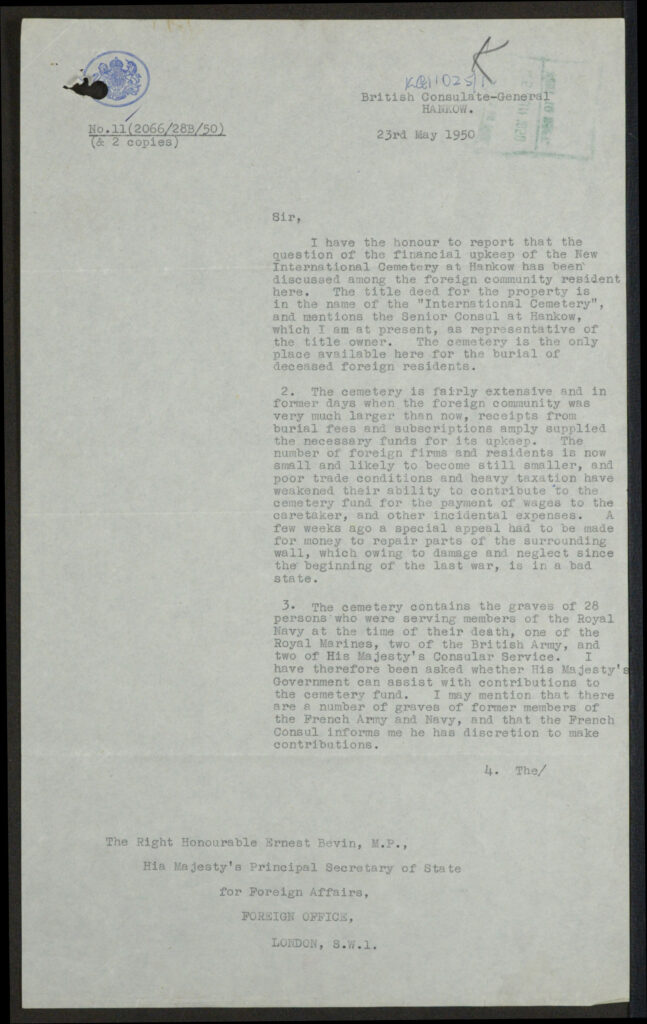

We get a sense of this in a despatch of May 23, 1950, from the British consul in Hankou to the Secretary of Foreign Office on the financial upkeep of the international cemetery in Hankou. Here the consul commented that “in former days when the foreign community was very much larger than now, receipts from burial fees and subscriptions amply supplied the necessary funds for its upkeep. The number of foreign firms and residents is now small and likely to become still smaller, and poor trade conditions and heavy taxation have weakened their ability to contribute to the cemetery fund for the payment of wages to the caretaker, and other incidental expenses.”

Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths

Regional China and the West, 1759-1972 contains selected registers of births, marriages, and deaths of British citizens in China registered at various legations and consulates. These records are not only useful for family history research but also contain valuable data for scholars.

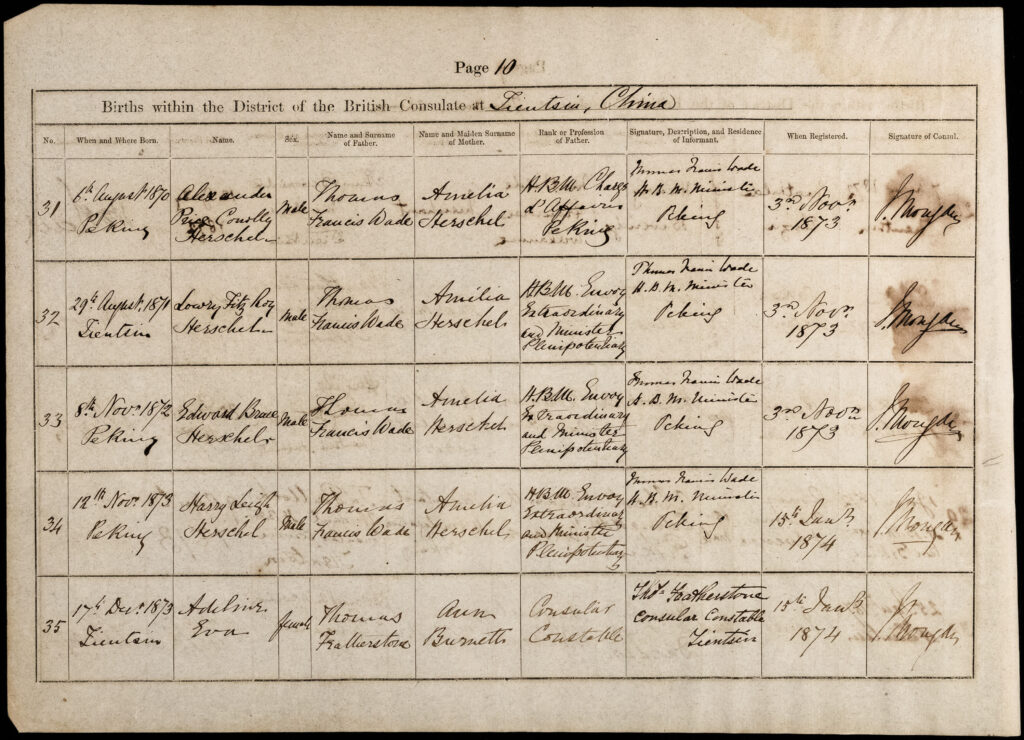

Sir Thomas Francis Wade was a British diplomat, interpreter, and sinologist who later became the first Professor of Chinese at Cambridge University. His diplomatic career is well represented in China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West, Part I: 1815-1881 and Part II: 1865-1905.

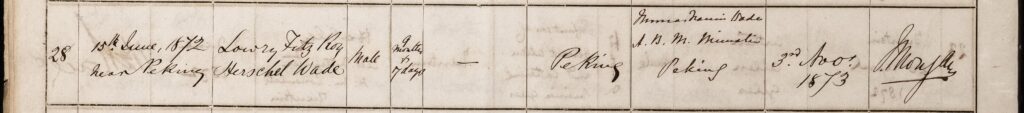

Through birth registers more information on Wade’s personal life can be obtained. For example, this document shows that four sons were born to Wade and his wife, Amelia Herschel, between 1870 and 1873 and their births were registered at Tientsin (now Tianjin), despite three out of the four sons having been born in Peking. A later register shows the couple also welcomed a daughter in 1875.

The births of all their sons were listed many months after their deliveries, which was not unusual at the time. Sadly, on the same day they recorded his birth, the death of their son Lowry is registered aged just nine months.

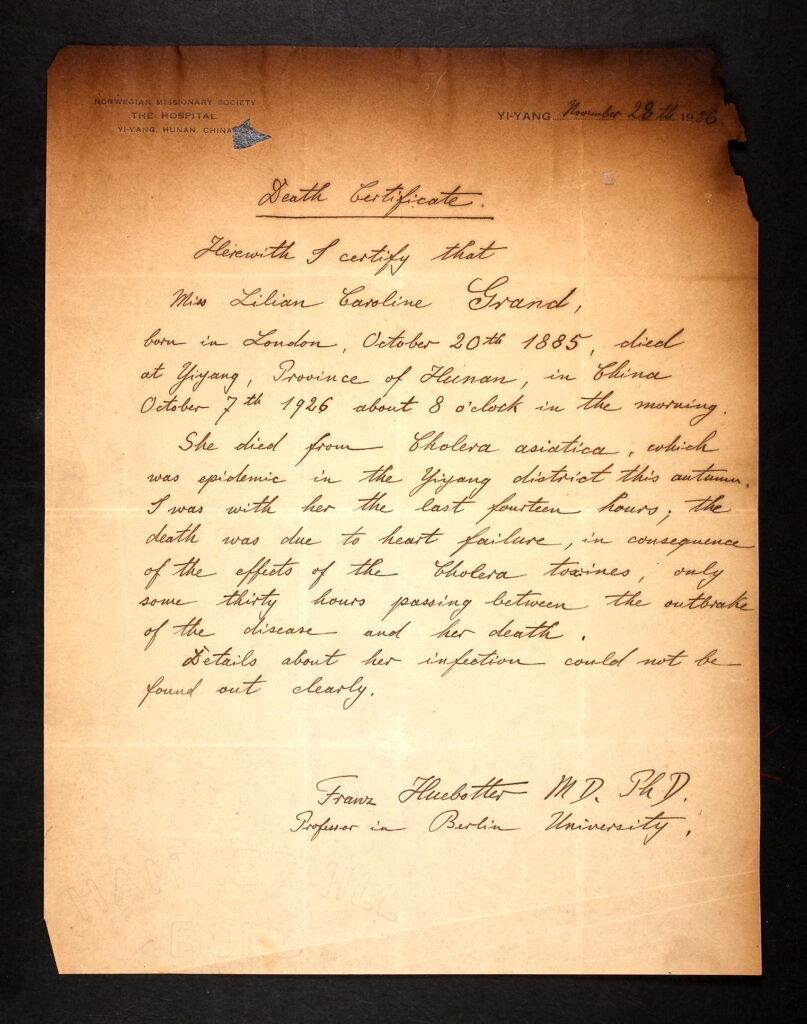

The death registers do not record a cause of death but included with them are some letters from individuals informing the authorities about a deceased person. These are useful to researchers as they can contain more details on the cause of the death and snippets of information about wider public health issues.

Throughout the death registers there are multiple letters informing the consulates of the deaths of individuals from typhoid, dysentery, and cholera, all bacterial diseases caused by contaminated food and water due to poor sanitation. As the registers show, British expatriates in China were severely impacted by these diseases.

This letter was received by the consulate from the Norwegian Missionary Society Hospital in Hunan informing them of the death of Miss Lilian Caroline Grand during a cholera epidemic. The doctor notes there had been an epidemic of cholera asiatica in the region that autumn and there was “only some thirty hours passing between the outbrake [sic] of the disease and her death.”

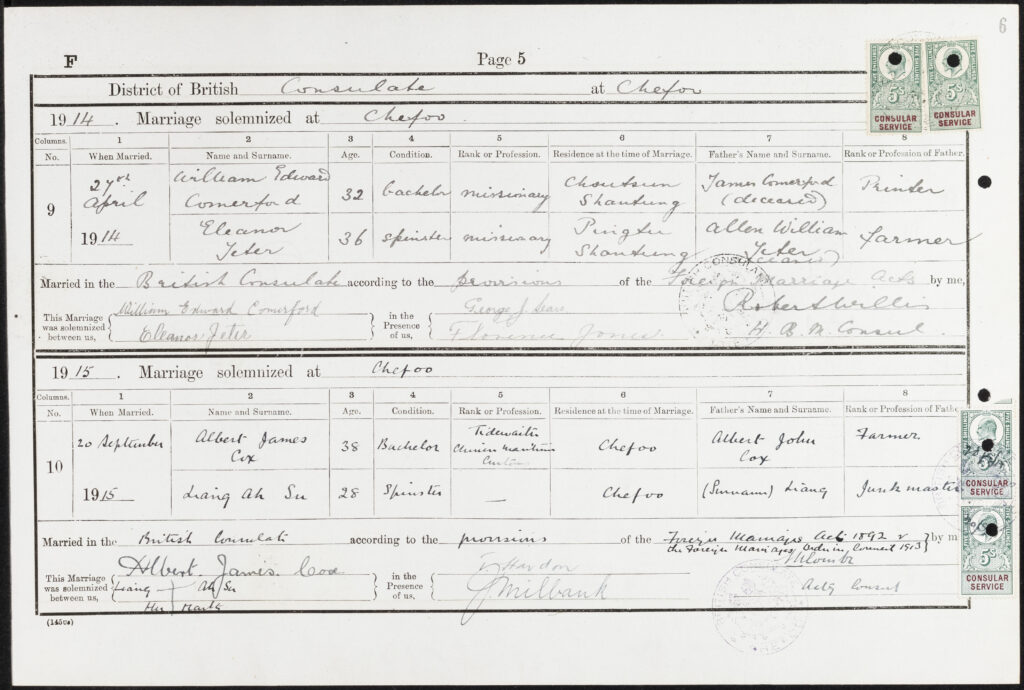

Marriage registers allude to happier times for British citizens in China, within the registers there are multiple examples of unions particularly between British missionaries working in China, as well as the marriages of consular staff and merchants engaged in trade.

This document shows the intermarriage between a British citizen and a woman of Chinese descent. Albert James Cox was a tidewaiter, a type of customs officer, for the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, when he married Liang Ah Su, the daughter of a junk master (a junk is a form of Chinese sailing boat). One wonders if their union was facilitated by their mutual maritime connection.

Registers of British Subjects

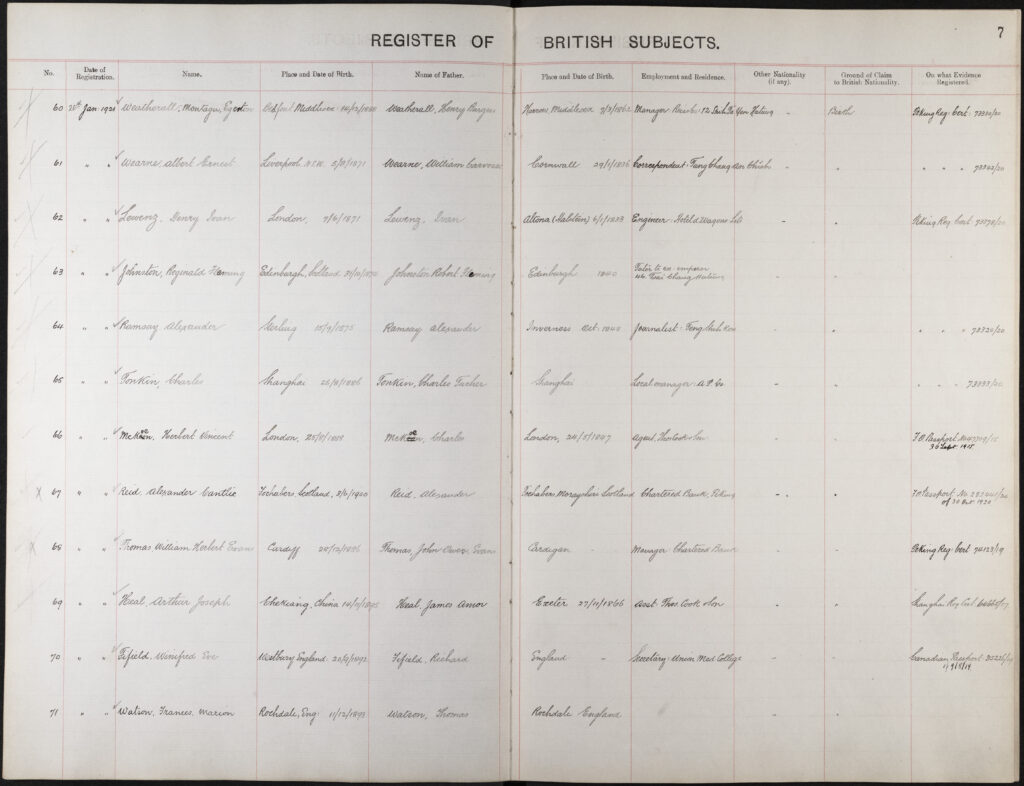

Present in the archive are registers of British subjects held by the various regional legations and consulates in China. This example dated 1921-1922 gives a snapshot of British citizens who were resident in Peking at the time, including journalists, bankers, and travel agents.

Also recorded in this register is Reginald Fleming Johnston, Scottish tutor to the last Chinese Emperor Puyi. He famously became a friend and confidant to the isolated Puyi after the revolution of 1911 and was one of only two foreigners ever allowed inside the inner court of the Qing Dynasty. Johnston later published a memoir, Twilight in the Forbidden City (1934), recalling his experiences as an eyewitness to this pivotal time in Chinese history.

A Light on Chinese-Western Relations

As a whole, this new archive provides a significant compendium of historical documents. Forming an ideal complement to Imperial China and the West, Part I and II, this collection sheds light on Chinese-Western relations as reflected from the local and regional lens, covering diplomacy, trade, law, and politics.

If you enjoyed reading about the sources found in this archive, you may like to read the following posts:

- China and Australia: Trade, Migration, and Politics in the Nineteenth to Early Twentieth Centuries

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- Researching the History of Shanghai Between the 1830s and 1950s

Blog post cover image citation: Great Britain. General Staff Topographical Section, and Great Britain. War Office General Staff Geographical Section. “Chinese Empire Showing Treaty Ports, Ports of Call and Places Open to British Trade, TSGS 2302.” British Library: Ministry of Defense Maps, Primary Source Media, 1907. Nineteenth Century Collections Online https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CHTGLO972914138/NCCO?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=1b4c3a87&pg=1