When reading through some documents contained within the State Papers’ SP94 (Spain) series recently, I was struck by some parallels between early-eighteenth century diplomatic relations and those of our current post-‘Brexit’ times. There is palpable tension in Anglo-Spanish relations from the letters exchanged between British Ambassador to Spain Paul Methuen and James Stanhope, Secretary of State for the Southern Department.

More broadly, this was a time of flux for European relations, with 1713 marking the end of what has been termed the first ‘global’ war: the War of Spanish Succession. Lasting for thirteen years, the war placed greater strain on European ties. Developing from a dispute over the succession of the Spanish throne when King Carlos II died childless in 1700 (leaving the Bourbon, Philippe Duc d’Anjou as his heir), England, Austria, and the Dutch Republic could not countenance a Franco-Spanish alliance dominating Europe. They therefore rejected the proposed succession by declaring war. After a thirteen-year campaign, the 1713 treaty concluding the war confirmed the succession of Philippe as Felipe V of Spain. As those letters show though, this succession prompted a re-evaluation of Anglo-Spanish trade arrangement.

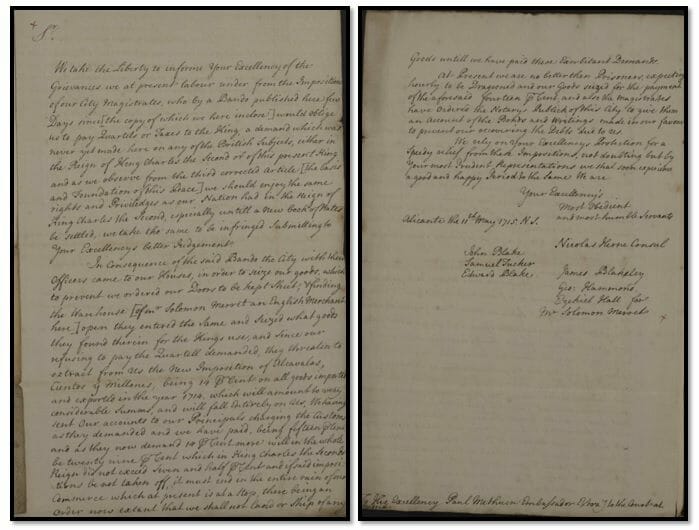

A central concern (at least from the British perspective) was maintaining favourable trading relations between the two countries. A revealing insight into the inner workings of Anglo-Spanish relations can be gleaned from a May 1715 letter, written by eight British Consuls to Ambassador Methuen before the subsequent treaty with Britain had been agreed. Methuen had been sent on a special mission to agree a new commercial treaty with Spain, having previously secured one with Portugal in 1703 (the “Port Wine Treaty”). In their letter, the Consuls wrote of the multiple grievances which were adversely affecting British trade; most significantly, the new customs levied on British goods and the unlawful seizing of British ships by Spanish officers. These new customs charges were deemed ‘exorbitant’; at 14%, the figure was almost double that which had been applied during King Carlos II’s reign. Desperate in their plea, the Consuls felt themselves ‘no better than prisoners’, just waiting to be ‘dragooned’. And so Methuen was left to secure a more favourable arrangement, restoring Anglo-Spanish trade to its previous status.

But this was no easy task. As the frequent letters between Methuen and Stanhope illustrate, there was a range of complex legal apparatus to navigate before any agreement was reached. As Methuen suggested in his 24th May letter, resolving complaints through the Spanish court was not a quick process: ‘the usual methods of proceeding upon them in this Court are so slow and dilatory’. Formal lawsuits would need to be drawn up, in the form of letters and affidavits, to officially register the British grievances.

Step in Juan Baptista Uzardi. Appointed as a British Agent, Uzardi effectively became a ‘middle man’ to relay British correspondence to the Spanish government. It was his task to secure the resolution of the British issues and restore trade to its previous footing. Methuen was optimistic that Uzardi would be able to secure a favourable outcome, having been familiar with the Spanish legal system.

However, delving deeper into the documents reveals that this was challenging even for a native speaker. Growing increasingly frustrated in his attempts to resolve the grievances, Methuen met Roman Catholic Cardinal Francesco del Giudice at Madrid in June, who assured him that King Felipe would respond. True to Methuen’s earlier lament about the painstakingly slow Spanish legal apparatus though, no response was forthcoming by July.

It is difficult not to become swept up in the emotion and desperation Methuen felt, as he forecast just how damaging it would be for Britain to sever its economic ties with Spain: it would ‘destroy the whole trade of the British Merchants in these ports’. For a diplomat with an illustrious career – he had previously served as Ambassador to Portugal and Lord of the Treasury – it is striking how such apparently innocuous trade dealings took their toll on Methuen. The more he grappled with the issue, the more his own health deteriorated, to the point that he was ‘scarce able to hold his pen’. After four months Methuen had to return to England due to ill health, leaving George Bubb Dodington to take over negotiations.

But was Methuen finally successful in his endeavours? Did he hang on long enough to reduce the customs charges back to their pre-war level? Or, in a striking parallel with our own post-Brexit times, was Britain left in the lurch, its trade agreements disrupted and facing increasing uncertainty?

Find out with the Spring 2017 release of State Papers Online: Eighteenth Century: Part III, home to the complete SP94 (Spain) series, where even such apparently trivial documents as these can offer a glimpse into wider political issues. To pre-register for a free trial, click here.