│by Lotta Vuorio, Gale Ambassador at the University of Helsinki│

The current circumstances caused by the global pandemic have highlighted the importance of digital primary sources. In Helsinki, the university library has (in large part) physically shut its doors, but luckily there is a great deal of primary source material available in, for example, the digital collections of the National Library of Finland, and the Helsinki University Library also offers students and staff numerous digital collections which include several Gale Primary Sources archives. Gale Primary Sources is a treasure trove where one can find sources for various types of research.

One might initially think Gale Primary Sources is most suitable for research focusing on Great Britain or America, since the collections seem mostly focused on those areas. However, I wanted to find out if the platform could also be helpful when studying Finnish history! What I found, in short, was a highly interesting peephole into Finnish War History before the Second World War. I have not specialised in Finnish nor War History in my own research, but I was curious to examine coverage of Finland, and Helsinki especially. So, let’s see the results of my brief exploration!

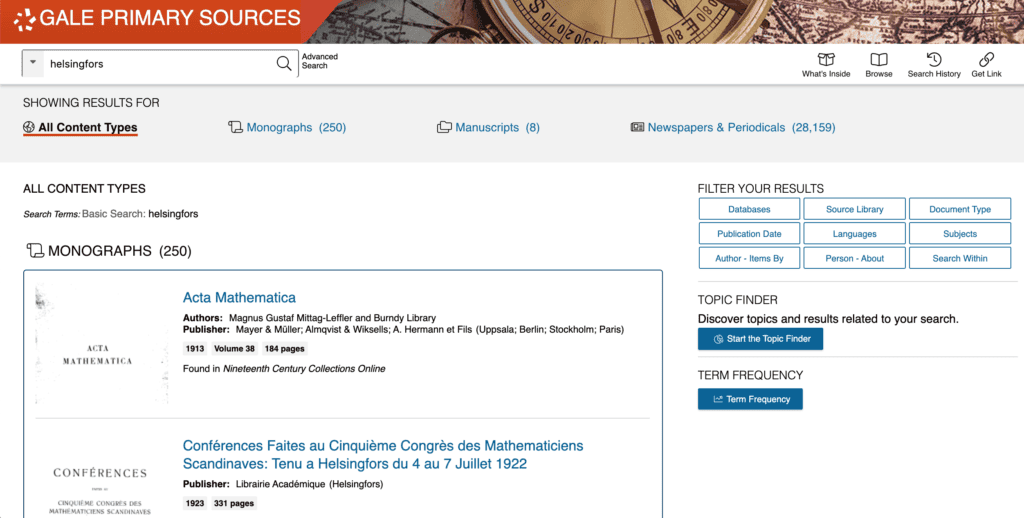

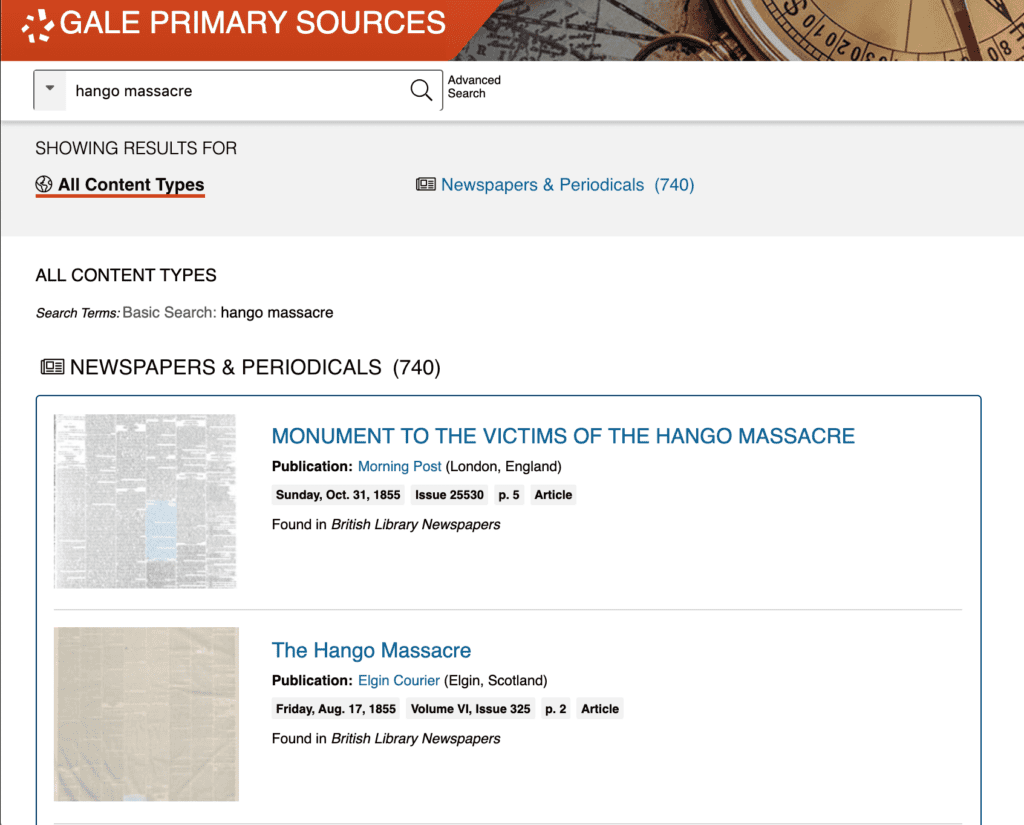

Searching “Helsingfors”

I began my exploration by simply searching for the keyword “Helsinki” in Gale Primary Sources. To be accurate, I used “Helsingfors” which is the Swedish name for Helsinki and more common in the material before the independence of Finland in 1917. (For further information about this, check out “100 years since Finland declared independence”). This is a useful tip to remember when conducting research – place names may change over time or be referred to differently for numerous political and social reasons, so it is worth searching for such variations to pull back more results. After completing my search, I was surprised by two things: firstly, a lot of the results referred either to trading or warfare, and secondly, there were a blinding number of materials! By merely searching for “Helsingfors” the search results offered 250 monographs, 8 manuscripts and 28,159 newspaper and periodical articles! As a result, it was apparent that I needed to limit my search somehow, and I decided to focus on the history of Finnish warfare and armed conflicts.

The Crimean War

After limiting the time span of my results to the nineteenth century using the date limiter in Gale Primary Sources, one significant event stood out: The Crimean War, a conflict fought from October 1853 to March 1856 between the Russian Empire and an alliance made up of Britain, the Ottoman Empire, France and Sardinia. Finland was involved because at that time it was part of the Russian Empire, in which, between 1809–1917, Finland was called “the Grand Duchy of Finland” or Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta in Finnish. I’m now going to look at some of the events that took place during the Crimean War that involved Finland and were covered in the British press at that time.

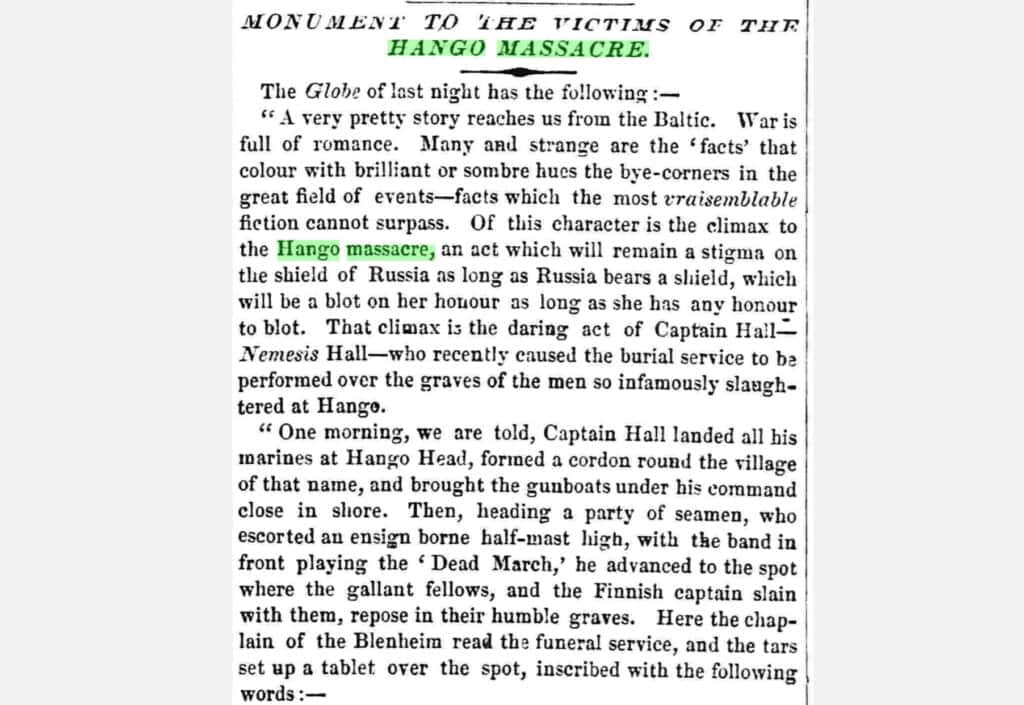

The “Hango Massacre”

When I browsed through the digital material during the war years, I found a particularly large amount of material from the so-called “Hango massacre”. This was the name that the English gave to the military clash in the Finnish city called Hanko in the summer of 1855. What happened, in short, was that the English sent boats to destroy an optic telegraph station, but a Russian Cossack unit destroyed the boats.1 Understandably, the British press gave the “Hango massacre” plenty of coverage, which can be seen in Gale Primary Sources: by searching for “Hango massacre” one can find 740 newspaper and periodical articles.

The “destruction of Lovisa”

It is surprisingly easy to follow the main events of the Crimean War from the Finnish point of view by using Gale Primary Sources. There are quite up-to-date reports on how the military conflict progressed that were published very soon after the events had taken their place. For example, the Sheffield Independent published a report on the “Destruction of Lovisa” on July 21, 1855 from a dispatch that was written on July 8, 1855 in “Hogland”. The dispatch that was written in “Hogland” (or Åland, an archipelago province belonging to Finland) explained the arrangements “for blowing up the fort and completely destroying the barracks” of the Finnish city called Loviisa. As a Finn myself, I cannot help but feel a little uneasy reading an emotionless, “third-party” depiction of destroying Svartholma’s fort – a building that has since been restored by the Finnish Heritage Agency.

How new technology impacted war reporting

What was special about contemporary coverage of the Crimean War was that it was one of the first “modern wars” due to the use of new technology such as the telegraph (invented in 1837). Telegraphs were used by the military for sharing strategies, but also for forwarding war reports to the press.2 Consequently it was the first war where the media were reporting in “real-time”. (Whilst drawing too much comparison between historical events and current situations has its dangers, I could not help but ponder whether the reporting of the Crimean War that can be found in British Library Newspapers was one of the first steps towards the reality we live in today, where news of COVID-19 is available instantly, day in, day out, from hour to hour, from moment to moment, and whether this development in technology is changing society’s approaches and understanding of news as it did to those exposed to the new telegraph technology in the nineteenth century.)

Coventry Herald, 5 May 1854, p. 2. British Library Newspapers, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EZ3245120400/GDCS?u=uhelsink&sid=GDCS&xid=21cd8d89

Unrest and murder in Finland quickly reported globally

Moving on to the twentieth century, I was curious whether the unrest at the beginning of the century appears in Gale’s archives. A wave of politically motivated murders created significant social unrest in Finland in the first years of the twentieth century. The murders were part of the resistance to the Russian oppression against the autonomy of the Grand Duchy of Finland that had started at the end of the nineteenth century. The most famous murder is that of the Governor-General of Finland, Nikolay Bobrikov, a Russian General who was the victim of an organised group of Finnish nationalists. The murder took place in the very centre of Helsinki on June 16, 1904, and was committed by a Finnish activist, Eugen Schauman. The news of the murder spread widely and fast thanks to the vast telegram network3 – General Bobrikov was shot before noon in Helsinki and the breaking news was published in Mexico the next morning (ironically, even before the information reached remote cities in Finland).

As expected, the news spread without delay to Britain as well. In Gale Primary Sources, 2,323 newspaper and periodical articles can be found by searching for “General Bobrikoff”, of which 22 were published on June 17, 1904. The British press were clearly aware of the strained situation in Finland already, and the Evening Telegraph wrote: “General Bobrikoff, the much-hated representative of the Tsar, who has been the instrument of Russia in carrying out repressive measures, has been shot, and it is believed mortally injured, by the son of a Senator. The news has caused the greatest excitement.” General Bobrikov died the morning the reports of the shooting were published, so the press could still not confirm the death in that day’s paper.

The murder continued to be discussed in the British press days later, and the Times analysed the event from the imperial point of view. However, though the murder itself was strictly disapproved, Finland gathered sympathies for its oppressed state by the international press, as Richard Back Jensen argues.4 This point of view is evident in this Times article as well, which writes:

“Amid the protests of the whole of Europe united in a common feeling of sympathy for the Finns and of rage and reprobation towards their oppressors, General Bobrikoff replied by suppressing the last remnant of their rights. – – History proves that the loyal establishment of a sincere régime of liberty is the safest means for closing the era of political crimes in a country.”

When browsing through dozens of articles published in the British press, one can be sure that one of the aims of the Finnish nationalists was achieved by this murder: widespread coverage of what was taking place in Finland.

The Finnish Civil War, 1918

After looking for articles from the very first years of twentieth century, I wanted to check whether the Finnish Civil War in 1918 was of interest to British newspapers. The Finnish Civil War was fought between Reds (a section of the Social Democratic Party, agrarian and industrial workers) and Whites (the conservative based Senate with the help of the German Imperial Army, middle-class and upper-class people). Because the name of this war has been contended both during and after the conflict, I decided to focus on Helsinki to make the search easier. I searched for “Helsingfors” and set the date limitation to look for results only in year 1918. Based on that search, Gale Primary Sources offered me 339 newspaper and periodical articles.

The occupation of Helsinki

The same accelerated speed of information transfer via the new telegram network that we saw impacting primary sources from 1904 was present in 1918 as well. During the civil war, Whites (with decisive German support) occupied Helsinki in the Battle of Helsinki on 11th – 14th April 1918. In other words, German troops marched to the city without facing any defensive lines. The Hull Daily Mail was wise enough to predict two days before the battle that, given “German warships have already been seen off Helsingfors, the occupation of which will probably take place in the very near future” – the very near future, it turned out.

On Thursday 11th April, Germans arrived in Espoo, a city next to Helsinki, and on Friday 12th April troops had arrived in central Helsinki. The Times broke the news of the occupation on Wednesday 17th April in an apologetic way: “The German occupation of Helsingfors took place on Friday, but was only known here, even to the Finnish Legation, to-day.” It seems that the British press had by then established a norm with regards to the time it took to break news, and needed to apologise for late reporting!

Winter Sports

Almost one year after the Finnish Civil War, the Times reported the condition of “Present-day Helsingfors” with a positive tune: “Helsingfors has practically regained its pre-war appearance” . The shadow to this story was that “the working classes have no love for the Germans”. The rest of the article was dedicated to praising the international (or rather Nordic) winter sports that were held in Helsinki in February 1919. In the eyes of the British press, Finland’s reputation as a winter- and sports-loving nation was already under construction – although the winter sports did not quite unite Finnish people because athletes belonging to the Sports Federation of Working People (Työväen Urheiluliitto in Finnish) were not allowed to take part.5

To summarise my exploration of the coverage of Finland in Gale Primary Sources, I was genuinely amazed by the amount of newspapers, periodicals, news pieces and articles concerning Finnish war history that I found. During the quarantine (and any other time!) I strongly recommend utilising Gale’s digital archives in your research. They are a worthy starting point for historians focusing on Finland as well as British or American history – indeed, it is fascinating to see Finnish history through the eyes of the international press, and this would certainly add an interesting angle to your research.

Interested in reading more about Finnish history, explored with primary sources? Check out Suomi mainittu! – Finland in American News in the Late Nineteenth Century or Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld – A Great Arctic Explorer of the Nineteenth Century.

Blog post cover image citation: “Helsingfors Occupied.” Times, 16 Apr. 1918, p. 6. The Times Digital Archive, https://link-gale-com.libproxy.helsinki.fi/apps/doc/CS100993680/GDCS?u=uhelsink&sid=GDCS&xid=f62ed578, combined with headlines from sources included in this post.

- The War History of Hanko: The Russian Fort. Viewed 5th April 2020. http://hangonsotahistoria.fi/index.php/en/historia-4/rysk-befastning/.

- Inventing Europe: ‘Eye-Witnessing’ the war in the Crimea: Telegraph vs. Camera. Viewed 5th April 2020. http://www.inventingeurope.eu/story/eye-witnessing-the-war-in-the-crimea-telegraph-vs-camera.

- Mila Oiva, Asko Nivala, Hannu Salmi, Otto Latva, Marja Jalava, Jana Keck, Laura Martínez Domínguez & James Parker: “Spreading News in 1904 – The Media Coverage of Nikolary Bobrikov’s Shooting”. Media History 2019. Open Access: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13688804.2019.1652090.

- Richard Bach Jensen: “The 1904 Assassination of Governor General Bobrikov: Tyrannicide, Anarchism, and the Expanding Scope of ‘Terrorism’”. Terrorism and Political Violence 2018, Vol. 30, No. 5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1445821.

- Urheilumuseo: Suomen talvikisat 1919 – Itsenäisen Suomen ensimmäiset suurkilpailut (The Winter Sports in Finland 1919 – The First Grand Competition of Independent Finland). Published 18.1.2019. Viewed 6th April 2020. https://www.urheilumuseo.fi/suomen-talvikisat-1919-itsenaisen-suomen-ensimmaiset-suurkilpailut/.