│by Lotta Vuorio, Gale Ambassador at the University of Helsinki│

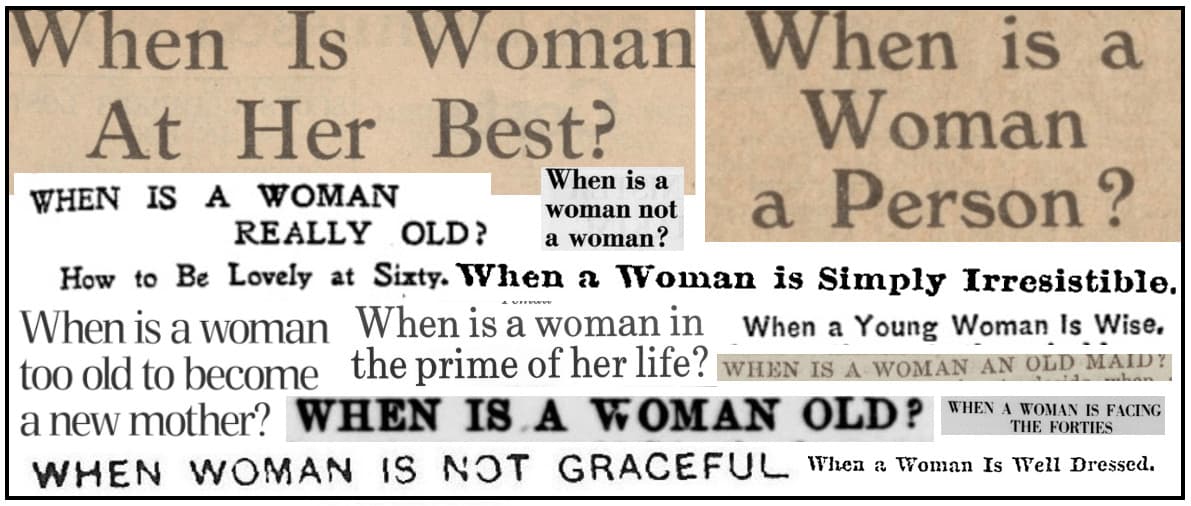

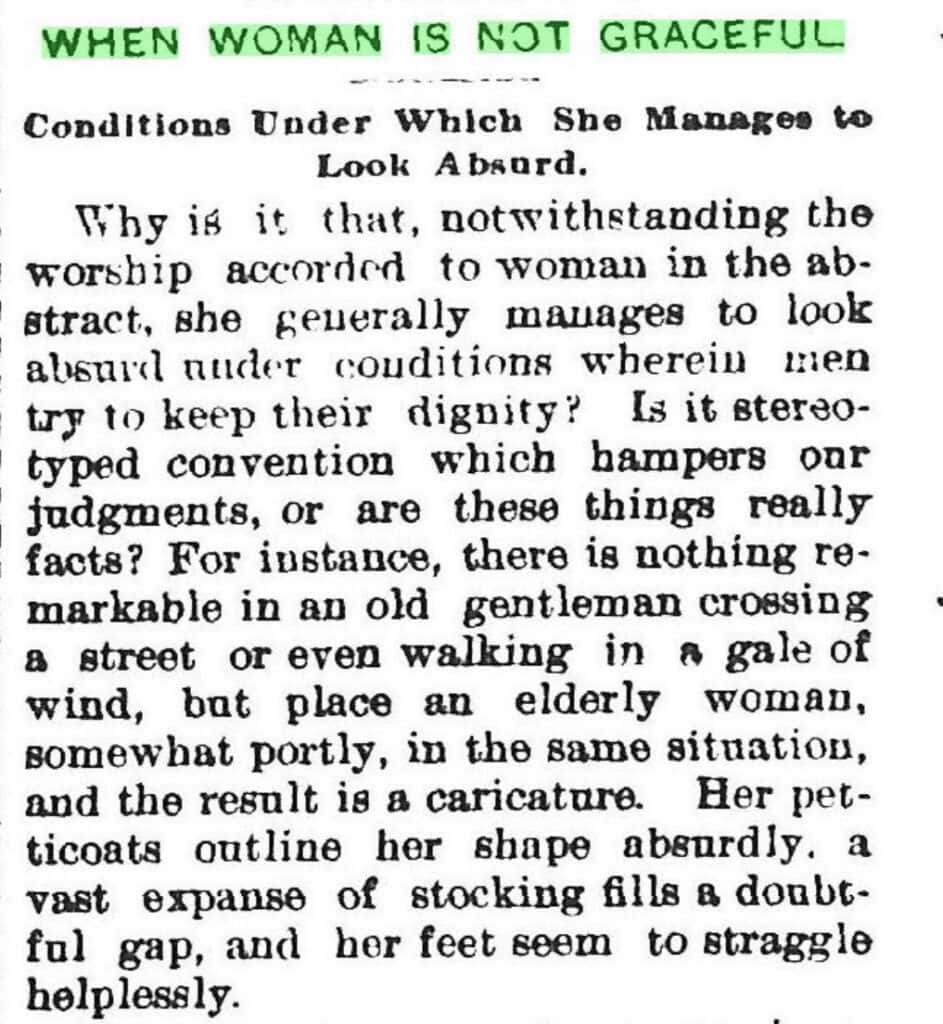

When I was preparing to deliver my first presentation as a Gale Ambassador, I ran into an interesting article called “When Woman is Not Graceful” in Gale’s Nineteenth Century Collections Online. The article was published in a newspaper called The Christian Recorder in 1895, and it portrays some of the “conditions under which she (a woman) manages to look absurd” – at least in the opinion of the anonymous writer. The article appears as an opinion piece by Graphic London and it expresses outspokenly all the descriptions connected to the stereotype of women who move clumsily. It says, “Few women can enter a carriage, mount the steps of a coach or hurry into a hansom gracefully, while the spectacle of a woman getting into a boat is far from pleasing”. The vast petticoats common in the nineteenth century and their effects on the ability of women to move are mentioned and criticised, and the writer finishes his piece by indicating the true form of grace: “A woman is only really graceful when she is at rest, lolling in a carriage or sitting in a drawing room or else dancing, when she has the genius for it.” I wanted to find this article again and began searching the Gale Primary Sources database. In doing so I came across many more newspaper articles with a heading that begins “When is a Woman…”. As I browsed through them I became intrigued, curious about the way articles in different newspapers described what was acceptable and admired in the appearance and behaviour of women. Below are some of the most fascinating examples I found.

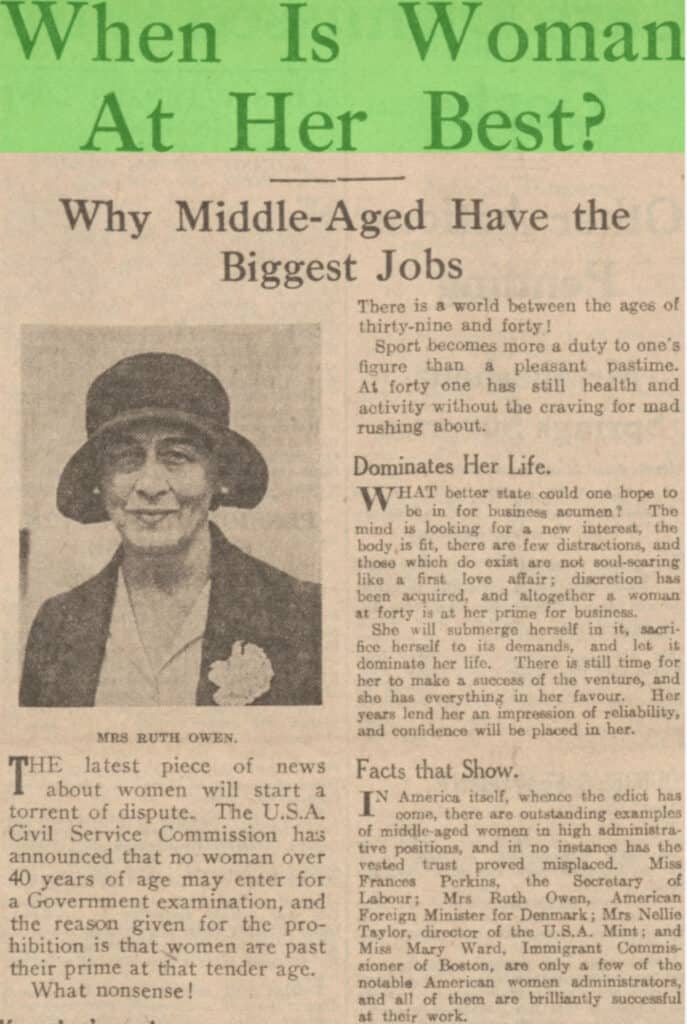

When is a woman “at her best”?

A point of discussion that appears frequently among the articles is the age of women. The question, as was asked in 1934 in the Dundee Courier, is “When is Woman at Her Best?”. In this article, the author lists several clever reasons against the claim by the USA Civil Service Commission that women were “past their prime at that tender age” of forty. The author opposes the claim strongly – “What nonsense!” – and argues that a woman in her forties “has acquired a saner and more restful outlook on life than even the thirties allowed” and reminds the reader “there is a world between the ages of thirty-nine and forty”. To conclude, the author provides a list of women and “facts that show” they are flourishing in middle-age: American Foreign Minister for Denmark Mrs. Ruth Owen (also in the picture next to the article), and Margaret Bondfield, Ellen Wilkinson and Lady Rhondda from Great Britain – to name just a few. Finally, to make the point of the article clear, the author declares: “I wonder what jealous, liverish old man gave voice to that fallacy!”

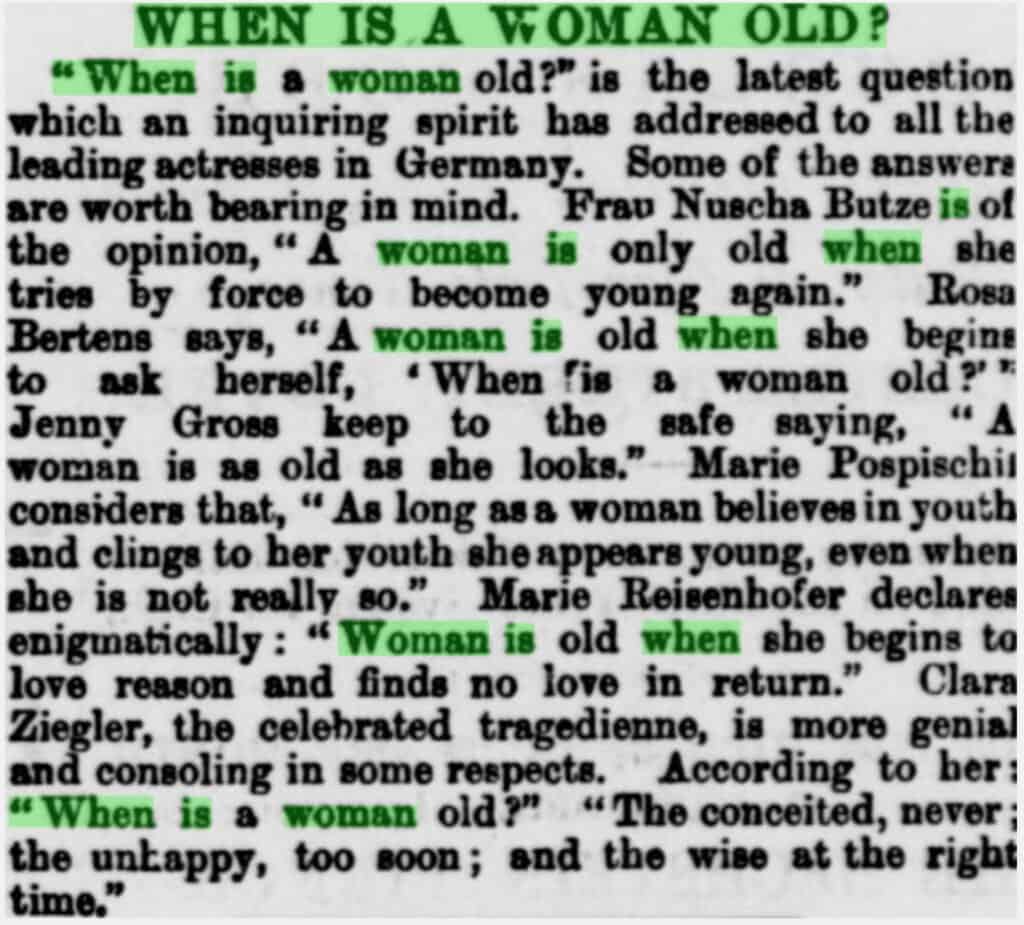

In relation to this article’s claim that women can be at their best in their forties, the article below from the Dover Express in 1896 asks when is a woman considered old. According to the article, the question had been put to “all the leading actresses in Germany” – and the discussion was apparently worth sharing in Great Britain as well!

Many of the answers given by these actresses – such as “A woman is only old when she tries by force to become young again” and “A woman is as old as she looks” – relate to appearance, leading me on to this popular dimension in my exploration of “When is a woman…” articles. But before jumping to that discussion, I wanted to share an age-related quip that was published in the Atchison Daily Champion in 1887 which suggests that the age of a woman was a delicate and personal matter that could be emotionally provocative. This got me thinking: why did age matter quite so much, and was it more or less important than today?

When is a woman “an old maid”?

Age and appearance are inextricably bound – but the link is particularly made in relation to women. It can be that wisdom comes with age, but so comes the fear of losing an attractive appearance. I’m curious why a woman’s beauty and youth have been culturally bound together for centuries, in Western cultures at least. One guess would be the importance of marriage and the role it played in a woman’s life. The look and appearance of a woman was meant to attract men for the purpose of marriage and having children (at least when it comes to my own historical research and the discourse on health and physical fitness in mid-nineteenth-century Britain), so the fear of not getting married because of an unattractive appearance was real and tangible.

Edinburgh Evening News let the cat out of the bag in 1885 with an article titled “When is a woman an old maid?” (found in Gale’s British Library Newspapers collection). The article discusses the question by pondering the appropriateness of calling a woman an old maid. It was told that “Ladies when unmarried never grow old, or grow old very slowly”. The article argues the fact that there were “a certain proportion of women left ‘unappropriated blessings’” could be seen as a positive thing: “After all, it is perhaps as well that a few women should remain free from the trammels of domestic life, in order that they may accomplish some work which otherwise might be left undone.”

When is the right time for a woman to marry?

Indeed, when is the right time to marry, so not to be called an “old maid”? The article below from the Milwaukee Journal (1892) had the answer in their article “When a Young Woman is Wise”. In the article it was suggested that “in general, it may be stated that a woman is wise who delays her marriage until she is 24 or 25 years of age”. The right age for a wedding was a question that concerned “alike the philosopher, the political economist, the moralist and the physician” – apparently, women and marriage were quite intriguing, interdisciplinary subjects! Interestingly, the suitable age for marriage was discussed more in relation to when a woman should marry than when was appropriate for a man.

Clearly the appearance and age of a woman intersected with discussion of marriage. But the secret for a charming appearance – what was that? An article from the Atchison Daily Champion in 1890 shared advice concerning “When a woman is well dressed”, a publication included in Gale’s collection Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers. It instructed, “If she is wise she will study out the colors and stuffs that suit her best”, and pointed out, “Gowns, gloves and hats in harmony are what, after all, make a well dressed woman”.

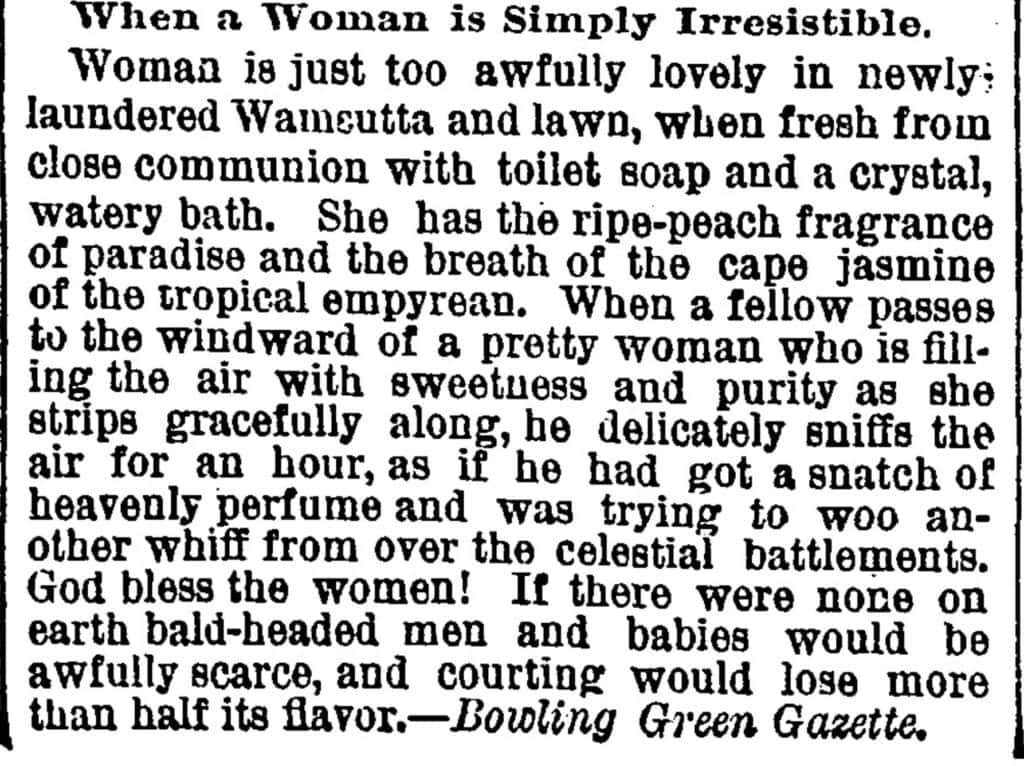

To conclude, I found articles that suggest the attractiveness of a woman was not only about the beauty of her physical features, but also her scent. In 1883 the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel described “When a woman is simply irresistible” with vivid language: “She has the ripe-peach fragrance of paradise and the breath of the cape jasmine of the tropical empyrean”. Further embellishing this fantasy, the article describes:

“When a fellow passes to the windward of a pretty woman who is filling the air with sweetness and purity as she strips [sic?] gracefully along, he delicately sniffs the air for an hour, as if he had got a snatch of heavenly perfume and was trying to woo another whiff from over the celestial battlements.”

After all these demands, wonders, ponderings, speculations and dreamy ideals, expressed so directly and sincerely in so many newspapers, I would say that the women of the times were true survivors to live with these exacting requirements or hopes. As stated in the last article: “God bless the women!”

Blog post cover image citation: A variety of cuttings from various newspaper archives in Gale Primary Sources.