│By Kat Weiss, Gale Academic Intern |

In the years leading up to the Nineteenth Amendment and after its ratification in 1920, American women realised that equality did not end with the right to vote. They recognised that they now had a civic duty to their country, to use this newfound right responsibly. With that realisation came a new question: now that women could participate in democracy, how would they learn to practice it?

They did not have access to the same education and resources as their male peers because the system was not built for them; they needed to find new ways to educate themselves and each other. With that in mind, the Nineteenth Amendment opened a new chapter in women’s history, one centred on learning how to exercise civic power. Using primary sources from Gale’s Nineteenth Century Collections Online, we can trace how women across the USA began to define and teach the responsibilities of citizenship.

“The time has almost gone by for talking woman suffrage. The time has come to talk citizenship.”

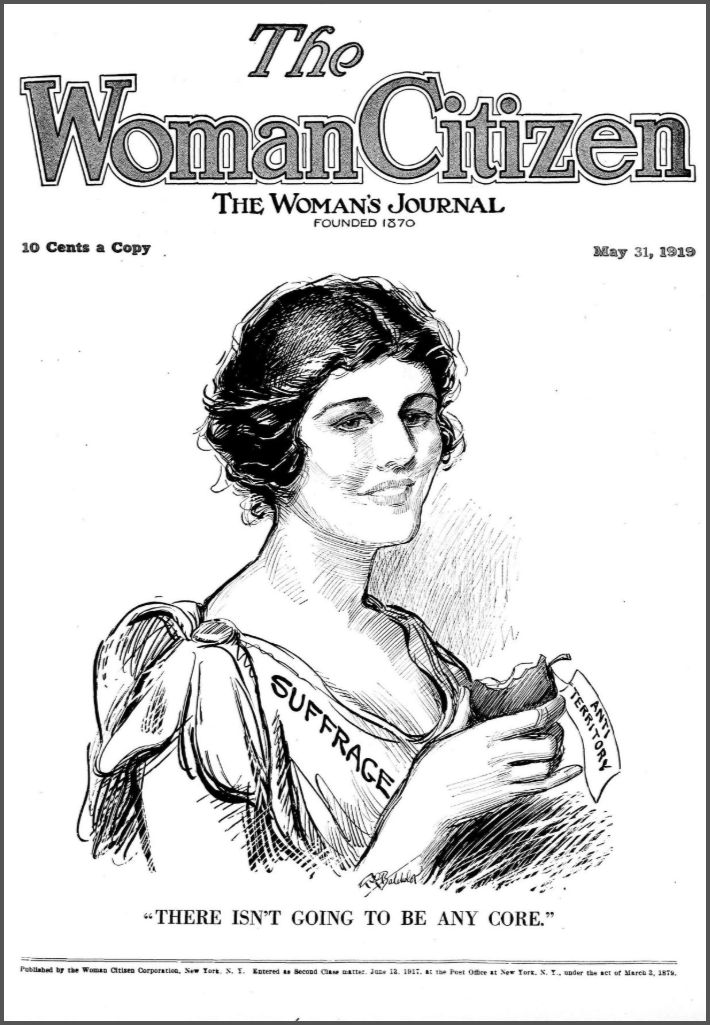

A 1919 pamphlet titled “As a Citizen – Are You Making Good?” marked a cultural turning point. The pamphlet, advertising The Woman Citizen, a weekly chronicle of women’s progress, invited readers to stay informed about politics, education, philanthropy, and civic life. The message was clear: suffrage had expanded rights, but it also brought new responsibilities.

Women were expected not only to vote, but to understand the democracy in which they now had a voice. However, these conversations did not begin only after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified; they had been years in the making, steadily building toward the realization of their goals.

“The first business for women is to become familiar with the mechanics of politics and imbued with the sense of civic responsibility.”

In “Women and Civic Education,” the periodical Women and the City’s Work emphasises the importance of organisations that had pioneered the fight for women’s suffrage, turning their efforts toward women’s civic education once the right was won. The publication called for collaboration among women, suffrage organisations, municipal leagues, and city clubs to take on the shared responsibility of educating their fellow women.

Fortunately, the idea that education was a shared responsibility continued to thrive even after the amendment passed. While women’s organisations and civic leagues worked locally, educational institutions stepped up on a national scale.

In “Our Civic Education,” colleges and universities across several states — including North Carolina, Arizona, and Wisconsin — developed structured educational courses for women voters. For example, the North Carolina College for Women organised programmes where women met daily for intensive sessions on local, state, and federal government. In Wisconsin, the University of Wisconsin partnered with the League of Women Voters to offer courses on constitutional rights, parliamentary law, and civic participation.

!["Woman Voter's Bulletin." Women Voters Bulletin, vol. VI, no. 6, June 1926, p. [1]. Nineteenth Century Collections Online](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image-2.jpg)

At the same time, civic education extended beyond classrooms and into libraries. In the article “Books for Citizens,” League of Women Voters librarian Alice K. O’Connor described her effort to gather texts on civics, government, and education, and curate them into accessible shelves that served as one-stop resources for those striving to become “less ignorant” voters. O’Connor’s simple yet impactful idea reflected a desire to transform libraries into classrooms of citizenship.

Together, these programmes democratised learning itself, carrying on the legacy of suffragettes by transforming education into the next steps of equality.

“Civics, or the duties of citizenship, not only ought to be taught in our schools, but carried on through all life.”

While many methods of civic education emphasised the importance of knowledge building through coursework and literature, others focused on learning by doing. The Civic Education League’s “Summer School of Civics” modelled this approach. Its curriculum included lectures but also incorporated fieldwork that used “the local community not merely as a place to study in, but as a convenient exemplification of the various economic, social, and political processes that were described in the various courses.”

By turning the community itself into a site of learning, the Summer School of Civics embraced an idea that still endures in civic education today, that democracy can be practiced as a form of education.

From Suffrage to Citizenship

The women who fought for suffrage understood that their victory in 1920 was not an endpoint, but a beginning. Through articles, coursework, community programmes, and collaboration, women redefined what it meant to be a citizen, despite having only been newly included. This period in women’s and educational history marked a shift: citizenship was no longer seen merely as a legal status, but as a practice that must be sustained through continual learning. Democracy depends not just on access, but on understanding.

In the years following the Nineteenth Amendment, women continued to transform classrooms and local communities into practicums of democracy. Their legacy endures in every effort today to make civic learning inclusive, accessible, and participatory. A century later, their lesson still stands: a right won must always be a right learned.

If you enjoyed reading about women’s suffrage, check out these posts:

- An Exploration of Women’s Liberation: Insights from Gale Primary Sources

- New Zealand – Trailblazers in Women’s Suffrage

- More Than a Storm in a Teacup – The Fight for Women’s Suffrage in the Tearoom

Blog post cover image citation: “History of Women Photographs.” History of Women, Primary Source Media. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/AOZAUX232789424/NCCO?u=intern&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=9c046b13&pg=194