| By Lindsay Whitaker-Guest, Associate Editor, Gale Primary Sources |

Gale Primary Sources recently released its latest module in the landmark legal history series, The Making of Modern Law. The Making of Modern Law: British Colonial Law: Acts, Ordinances, and Proclamations from the Colonies, 1900-1989 contains legislation from all corners of the British Empire and was digitised from the Colonial Office collections held at the National Archives in the UK.

The legislation in the archive covers all aspects of colonial life in a century which saw British-held territories transformed by war, disease, rebellion, and decolonisation. However, for this post we will examine how the empire governed one fundamental aspect of domestic life: marriage.

The Problem of Legal Pluralism

Among the many areas of governance represented in the archive, marriage laws provide a particularly revealing lens for examining how the British Empire navigated legal pluralism, reflecting the coexistence of multiple legal orders within a single territory. Marriage touches on religious authority, customary practice, personal status, inheritance, and gender norms. These issues made marital arrangements both contentious and difficult to legislate in colonial societies.

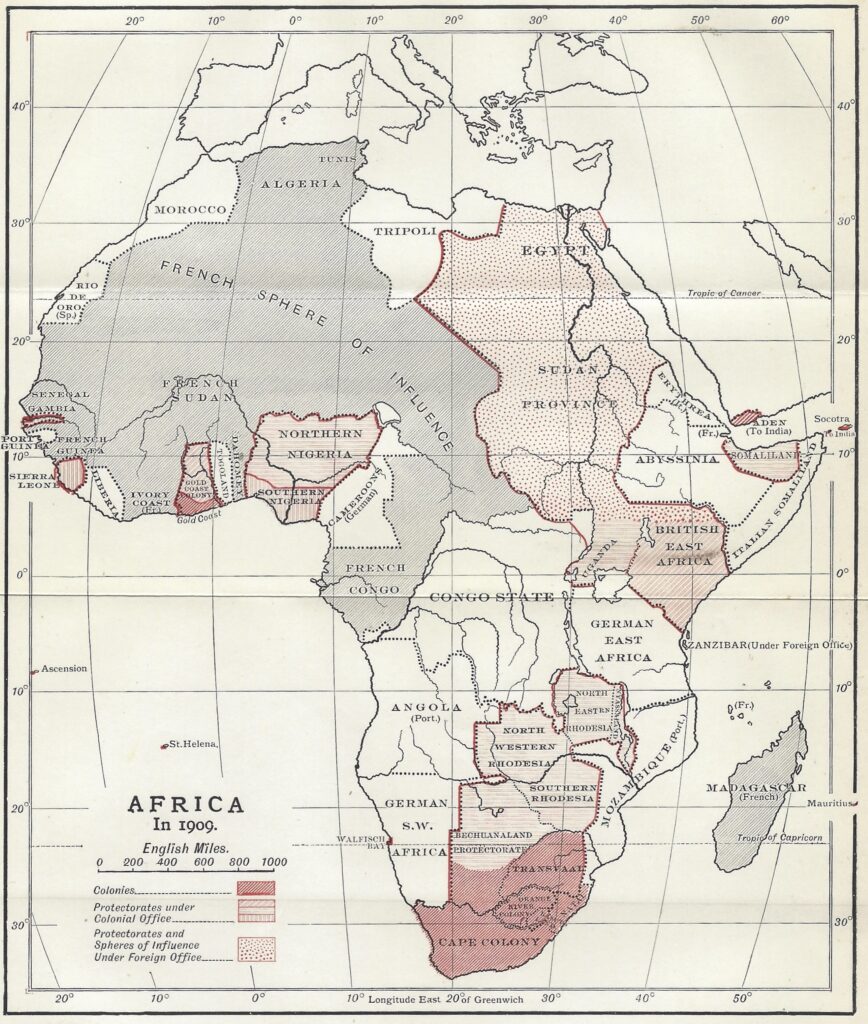

Under colonial rule, conflicts over how to treat marriage as a legal reality arose between Indigenous legal systems and the laws imposed by imperial powers. In many British colonies, especially in Africa, missionaries, settlers, and colonial officers each brought different expectations regarding marriage, divorce, and inheritance. The result was a complex hierarchy of overlapping legal regimes.

Further complicating the legal landscape was the selected application of marital (and other “personal”) laws. Different personal laws could apply to distinct religious or ethnic communities within the same country. Marriage laws required the careful navigation of Christian expectations, customary norms, and, later, the needs of immigrant populations.

The Marriage Question

In the late nineteenth century British legislators introduced marriage ordinances into multiple African countries based on the Gold Coast/Lagos Marriage Ordinance of 1884 with little thought as to whether this was suitable for the conditions and people in the varied territories.

After the introduction of the ordinance Kenyan legislators quickly realised it was not suitable for the needs of its population and developed a pronouncedly plural marriage regime. Christian marriages among British settlers followed English law, while African marriages continued to be regulated under customary law.

This was confirmed by the East Africa Marriage Ordinance, 1902, which allowed for the marriages of Africans and non-Christians to take place without registration and permitted polygamous marriages, which were traditional and legal under customary laws.

Africans who had converted to Christianity were compelled to register and marry under the ordinance by their church, which changed the personal laws applicable to them. This altered their rights by bringing them under English rules when it came to divorce and inheritance. These differing legal regimes proved problematic for the increasing number of African Christians.

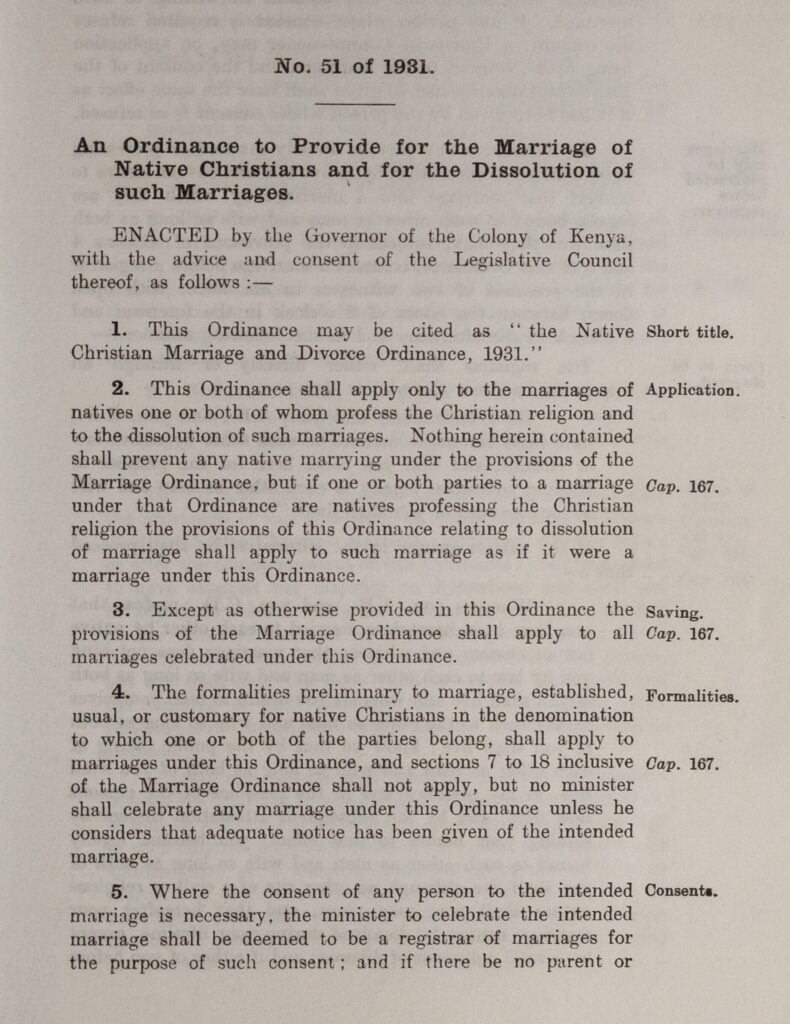

Marriage laws were modified to alleviate the issue in 1931 by the Native Christian Marriage and Divorce Ordinance which created a category for African Christians to regulate their marriages. It also outlawed such Indigenous practices as polygamy. This, of course, did not solve the problem for African Christians who wanted to maintain traditional practices when it came to marriage and succession.

The ordinance did not recognise the validity of customary marriages among African Christians. As a result, in inheritance cases where a man had both an ordinance marriage and a customary marriage, the customary wife was not legally recognised as an heir. Customary wives and children were often excluded from property rights, reinforcing a hierarchy that privileged Christian and English-derived forms of marriage.

The Impact of Immigration

New patterns of immigration also impacted marriage laws. In the late nineteenth century, thousands of South Asians emigrated to Kenya to work on railway construction. At the time, Asian immigrants were governed by separate personal laws according to their religion. Ordinances were later enacted to regulate Hindu and Islamic (referred to as ‘Mohammedan’) marriages, reflecting the country’s increasingly complicated legal and ethnic structures.

By the mid-twentieth century, Kenya ended up with a confusing system that included no less than five distinct categories of laws relating to marriage: customary marriage, civil marriages governed by law (which mirrored the English system), Hindu marriages, Christian marriage, and Islamic marriage.

Colonial systems were continually amended in response to demographic changes, administrative concerns, and missionary influences. The growing involvement of colonial governors in legislative matters is especially visible in debates surrounding morality, monogamy, and the regulation of African Christian marriage.

From Indirect Rule to Increasing Intervention

British colonial ideology initially promoted “indirect rule” – governing through established local structures. In practice, Kenya’s marriage legislation shows how this principle eroded over time. The number of ordinances expanded significantly from the early to mid-twentieth century, and the level of state oversight increased correspondingly.

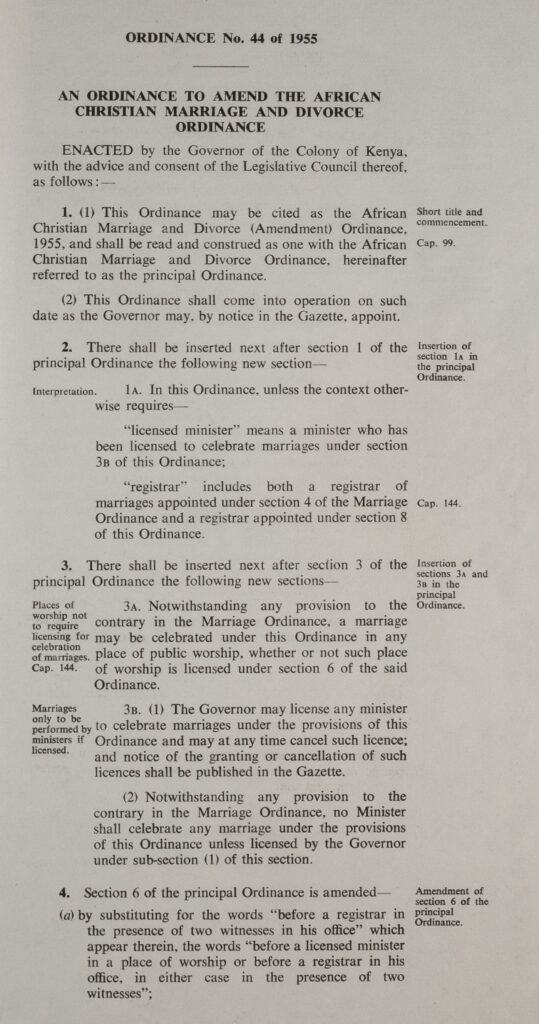

A keyword search for “marriage” within the archive illustrates this trend. Between 1900 and 1930, only seven documents appear. From 1931 until independence in 1963, the number rises to twenty-two. Legislation became not only more frequent but also more controlling. For instance, from 1955 onward, only ministers licensed by the Governor could perform the marriages of African Christians, reinforcing colonial authority over personal and religious life.

What began as a hybrid system that appeared to respect local customs evolved into one marked by increasingly rigid boundaries. Marriage, which was once largely managed through Indigenous customs and leaders, became entangled in colonialist moral policy and administrative intervention.

Colonial Legacy

The plural legal regime established under colonial rule had long-lasting consequences for Kenya. At independence in 1963, the country inherited a fragmented set of civil, customary, and religious marriage laws. This patchwork persisted for decades, generating disputes over inheritance, child legitimacy, and women’s rights.

It was not until the passage of the Marriage Act of 2014 that Kenya fully harmonised its marriage laws into a single statute. This act superseded the colonial-era ordinances and placed all recognised forms of marriage under the same legislation. More than fifty years after independence, Kenya resolved a problem originally created during the early years of British administration.

New Insights

This post has focused on just one country and one area of personal law. Yet the broader archive contains the acts, ordinances, and proclamations of seventy-one colonial territories which represent fifty-two modern nations.

Within this legislation lies countless stories about how colonial governments shaped and constrained the daily lives of the people they ruled. I look forward to seeing how students and scholars use this collection to uncover new insights into the legal histories of former British colonies.

If you enjoyed reading about marriage laws, check out these posts:

- Courting Primary Sources: Historical Opportunities from Briefs filed with the U.S. Courts of Appeals

- Celebrating South Africa’s Independence “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika”

- Indentured Indian Workers and Anti-Colonial Resistance in the British Empire

Blog post cover image citation: A collage of images from this post and The Making of Modern Law: British Colonial Law: Acts, Ordinances, and Proclamations from the Colonies, 1900-1989.