|By Margaux Lapierre, Digitisation Project Manager, British Library│

The digitisation of rare and historic materials not only makes these materials more accessible, it also supports preservation and cultural stewardship. For institutions like the British Library, where collections of printed heritage may be large and fragile, digitisation helps to safeguard materials while expanding their visibility and value in research, education, and public engagement.

Projects such as Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Part III (ECCO III), which will be released in March 2026, are a model for how digitisation and conservation complement and strengthen one another. They provide an illustration of how a library can protect the material integrity of its holdings and fulfil its mission to provide access to knowledge for as wide an audience as is possible.

Reducing Handling: A Core Conservation Priority

In heritage institutions, physical handling is one of the most direct hazards to historic collections. In the case of eighteenth-century materials—some of which have been printed on acidic paper, bound with decaying adhesives, and held in suboptimal conditions for decades—every touch carries a risk. Pages may tear or detach; bindings may split; ink and pigments may fade or transfer.

Digitisation provides a permanent alternative to repeated access. By creating high-resolution digital surrogates, projects like ECCO III eliminate the need for daily retrieval of originals. Once imaged, physical items can be stored in preservation-safe environments, retaining their structure and condition for generations to come.

Conservation Enables Digitisation—and Is Enabled by It

Digitisation and conservation are not opposing forces—they work best in tandem. Far from replacing conservation, digitisation relies on it. In a project like ECCO III, materials undergo pre-digitisation assessment and treatment before digitisation. This can include stabilising fragile bindings, repairing tears and removing surface dirt. A conservation-first approach is built into our digitisation workflow.

One of the most valuable conservation outcomes of digitisation is the safe access it enables to restricted materials—those too fragile to handle. Historically, items such as the two discussed below would have been withdrawn from use altogether, their content effectively hidden from public view in order to preserve their condition.

Digitisation changes that. Even the most delicate or damaged items can be shared digitally in classrooms and research settings or online, for remote scholars and in exhibitions all without risking the originals.

With the launch of ECCO III, hundreds of previously unavailable items will be open to study and enjoy, without compromising their survival.

Case Study 1: Hortus Siccus Britannicus, James Dickson

A standout example within ECCO III is James Dickson’s Hortus Siccus Britannicus, a remarkable collection of pressed British plant specimens affixed to paper and labelled according to Linnaean classification. Works such as this, combining organic material and early printing, are notoriously fragile.

There are numerous dangers to its conservation: dried plants can crumble or detach with the lightest motion and environmental shifts may cause warping or page distortion. Repeated viewing is virtually impossible without permanent damage.

Because of this, such works are often restricted from public access and rendered invisible. Digitisation reverses this. With high-resolution imaging:

- All plants, labels, and notes are preserved in detail.

- Researchers can study structure, Latin taxonomy, and layout remotely.

- The original is safely locked away in a controlled conservation environment.

Without digitisation, this work could not have fulfilled its scholarly or educational potential. Digitisation makes it visible without making it vulnerable.

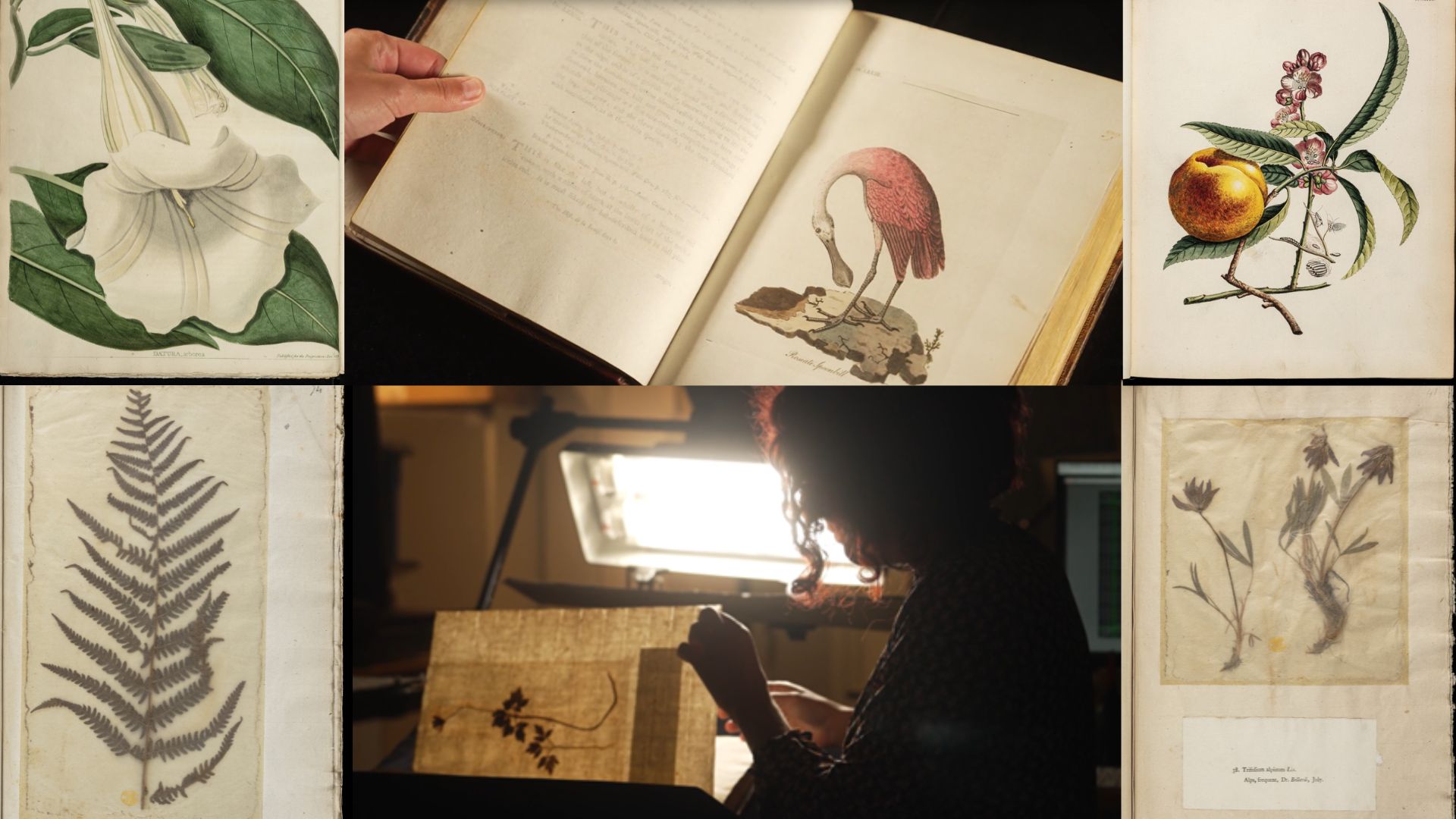

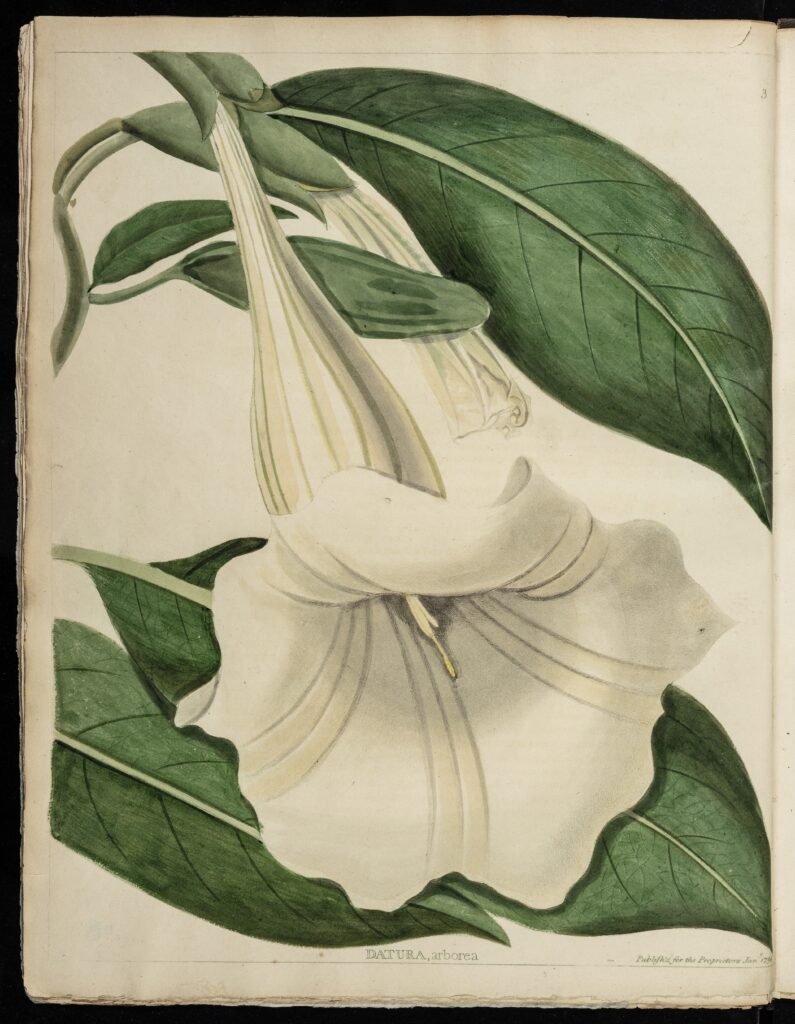

Case Study 2: Botany Displayed, John Thompson

John Thompson’s Botany Displayed is another botanical gem in ECCO III. With hand-coloured plates of native and exotic flora, it is both a scientific and artistic artefact. But that art comes at a cost: hand-painted pigments are sensitive to light, touch, and abrasion.

Conservation challenges include:

- Pigment fading or flaking when exposed.

- Stress on bindings when opening to view large plates.

- Vulnerability to foxing (reddish-brown spots on old paper), water damage, and ink bleed.

Digitisation offers a way to capture the beauty and intricacy of these image plates without subjecting the physical book to risk. Once scanned:

- The colours and illustrations are preserved at their peak.

- Scholars and students can zoom in, compare, or annotate.

- The original no longer has to be handled, protecting both text and image.

This is a perfect example of how digitisation can preserve the integrity of rare materials while extending their reach to audiences worldwide.

Why ECCO III Matters

While the benefits of digitising books are clear, the true value of ECCO III lies in its scale and coordination. As a project covering thousands of titles from across the British Library’s holdings (and other institutions), ECCO III enables collection-wide preservation strategies and creates a public, scholarly, and institutional memory of materials that may one day become too fragile to handle at all.

Above all, the project allows conservation and digitisation teams to work in dialogue—prioritising materials that are rare, at risk, and high-value in both scholarly and physical terms.

A Strategic Partnership

In the world of rare books and printed heritage, digitisation is not a substitute for conservation—it is its strategic partner. ECCO III demonstrates what can be achieved when conservation goals are built into a large-scale digital project at an early stage:

- Fragile books are removed from circulation and stabilised.

- Restricted materials are safely made accessible to a global audience.

- Illustrations, pigments, annotations, and structures are recorded in detail.

- Public engagement increases.

ECCO III stands as a model for how twenty-first-century technology can serve eighteenth-century heritage—not by replacing its material reality, but by respecting its fragility and amplifying its voice. This is conservation not just of books, but of access, knowledge, and history itself.

If you enjoyed reading about ECCO III check out these posts:

- Perfecting the Elevator Pitch: Using Gale Primary Sources to Unpack Intellectual History

- An Eighteenth-Century Intersectional Feminist? Exploring the Life of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in Eighteenth Century Collections Online

- Who was the Chevalier de Saint-Georges?

Blog post cover image citation:

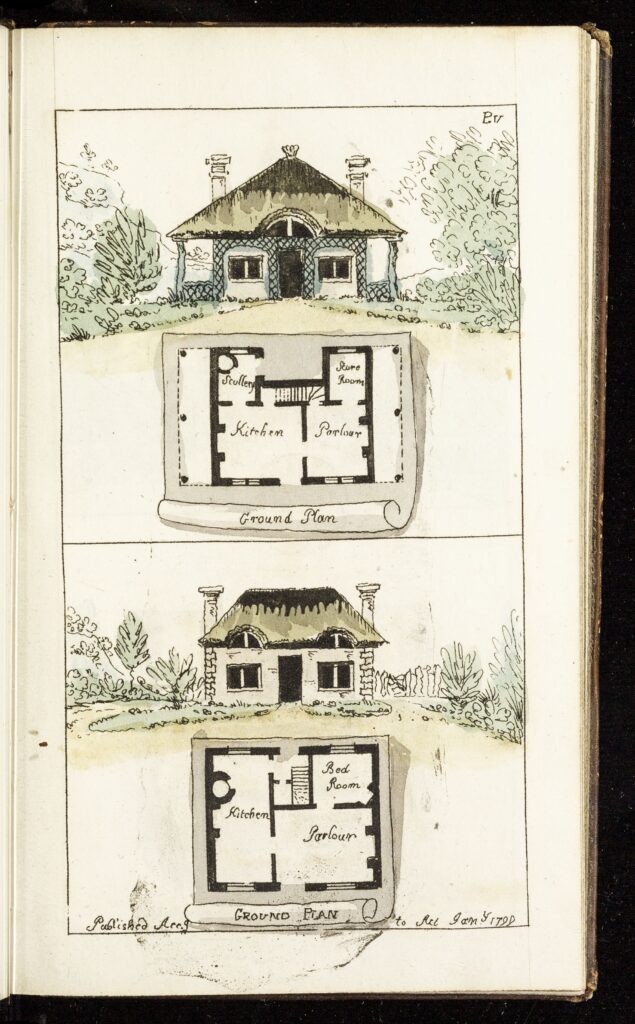

Margaux Lapierre checking a book onsite at the British Library prior to its digitisation.